Though he never said so directly, we might expect that Situationist Guy Debord would have included Saturday Night Live in what he called the “Spectacle”—the mass media presentation of a totalizing reality, “the ruling order’s nonstop discourse about itself, its never-ending monologue of self-praise.” The slickness of TV, even live comedy TV, masks carefully orchestrated maneuvers on the part of its creators and advertisers. In Debord’s analysis, nothing is exempted from the spectacle’s consolidation of power; it co-opts everything for its purposes. Even seeming contradictions within the spectacle—the skewering of political figures, for example, to their seeming displeasure—serve the purposes of power: The spectacle, wrote Debord, “is the opposite of dialogue.”

So I wonder, what he might have made of the appearance of cult writer and Beat pioneer William S. Burroughs on the comedy show in 1981? Was Burroughs—a mastermind of the counterculture—co-opted by the powers that be? The author of Junkie, Naked Lunch, and Cities of the Red Night also appeared in a Nike ad and several films and music videos, becoming a “presence in American pop culture,” writes R.U. Sirius in Everybody Must Get Stoned.

David Seed notes that Burroughs “is remembered by many members of the intelligentsia and glitterati as dinner partner for the likes of Andy Warhol, David Bowie, and Mick Jagger,” though he had “been a model for the political and social left.” Had he been neutered by the 80s, his outrageously anarchist sentiments turned to radical kitsch?

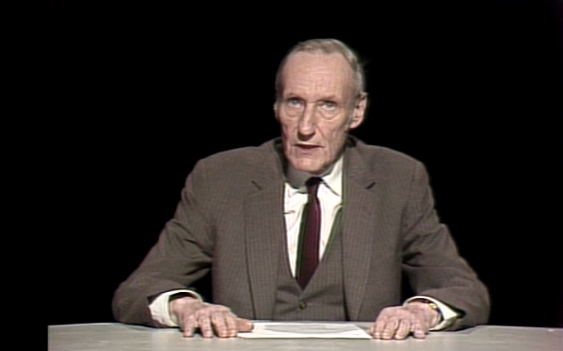

Or maybe Burroughs disrupted the spectacle, his droning, monotonous delivery giving viewers of SNL exactly the opposite of what they were trained to expect. The appearance was his widest exposure to date (immediately afterward, he moved from New York to Lawrence, Kansas). One of the show’s writers convinced producer Dick Ebersol to put Burroughs on. In rehearsal, writes Burroughs’ biographer Ted Morgan, Ebersol “found Burroughs ‘boring and dreadful,’ and ordered that his time slot be cut from six to three and a half minutes. The writers, however, conspired to let his performance stand as it was, and on November 7, he kicked off the show sitting behind a desk, the lighting giving his face a sepulchral gauntness.”

In the grainy video above, Burroughs reads from Naked Lunch and cut-up novel Nova Express, bringing the sadistic Dr. Benway into America’s living rooms, as the audience laughs nervously. Sound effects of bombs and strains of the national anthem play behind him as he reads. It stands as perhaps one of the strangest moments in live television. “Burroughs had positioned himself as the Great Outsider,” writes Morgan, “but on the night of November 7 he had reached the position where the actress Lauren Hutton could introduce him to an audience of 100 million viewers as America’s greatest living writer.” I’m sure Burroughs got a kick out of the description. In any case, the clip shows us a SNL of bygone days that occasionally disrupted the usual state of programming, as when it had punk band Fear on the show.

Perhaps Burroughs’ commercial appearances also show us how the counterculture gets co-opted and repackaged for middle-class tastes. Then again, one of the great ironies of Burroughs’ life is that he both began and ended it as “a true member of the midwestern tax-paying middle class.” The following year in Lawrence, Kansas, he “caught up on his correspondence.” One student in Montreal wrote, imagining him in “a male whorehouse in Tangier.” Burroughs replied, “No… I live in a small house on a tree-lined street in Lawrence, Kansas, with my beloved cat Ruski. My hobbies are hunting, fishing, and pistol practice.” Did Burroughs, who spent his life destroying mass culture with cut-ups and curses, sell out—as he once accused Truman Capote of doing—by becoming a celebrity?

Perhaps we should let him answer the charge. In answer to a fan from England who called him “God,” Burroughs wrote, “You got me wrong, Raymond, I am but a humble practitioner of the scrivener’s trade. God? Not me. I don’t have the qualifications. Old Sarge told me years ago: ‘Don’t be a volunteer, kid.’ God is always trying to foist his lousy job not someone else. You gotta be crazy to take it. Just a Tech Sergeant in the Shakespeare Squadron.” Burroughs may have used his celebrity status to his literary advantage, and used it to pay the bills and work with artists he admired and vice-versa, but he never saw himself as more than a writer (and perhaps lay magician), and he abjured the hero worship that made him a cult figure.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016.

Related Content

Beat Writer William S. Burroughs Spreads Counterculture Cool on Nike Sneakers, 1994

The “Priest” They Called Him: A Dark Collaboration Between Kurt Cobain & William S. Burroughs