As a New York City subway rider, I am constantly exposed to public health posters. More often than not these feature a photo of a wholesome-looking teen whose sober expression is meant to convey hindsight regret at having taken up drugs, dropped out of school, or forgone condoms. They’re well-intended, but boring. I can’t imagine I’d feel differently were I a member of the target demographic. The Chelsea Mini Storage ads’ saucy regional humor is far more entertaining, as is the train wreck design approach favored by the ubiquitous Dr. Jonathan Zizmor.

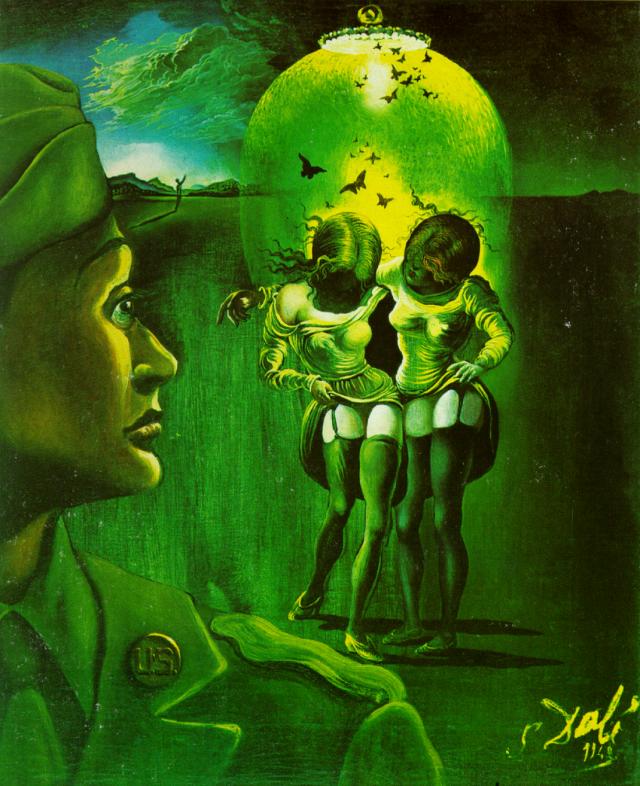

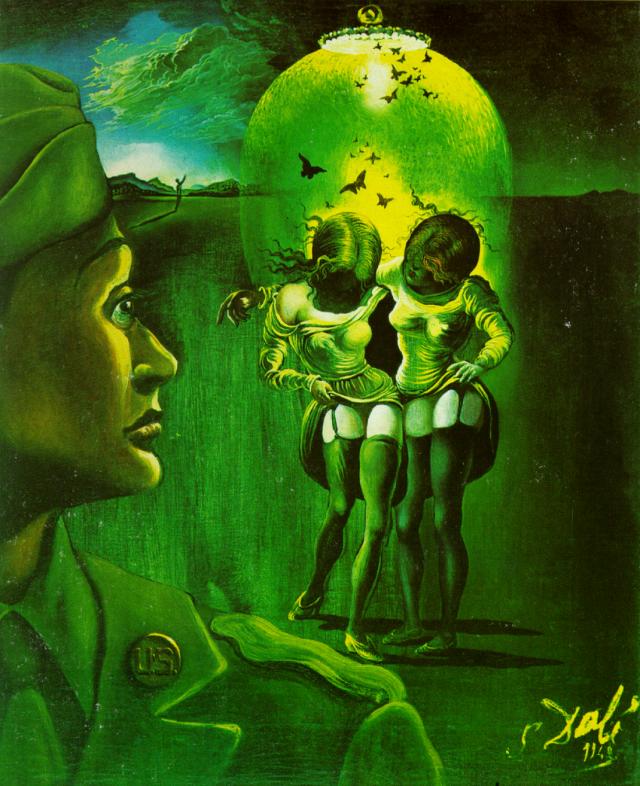

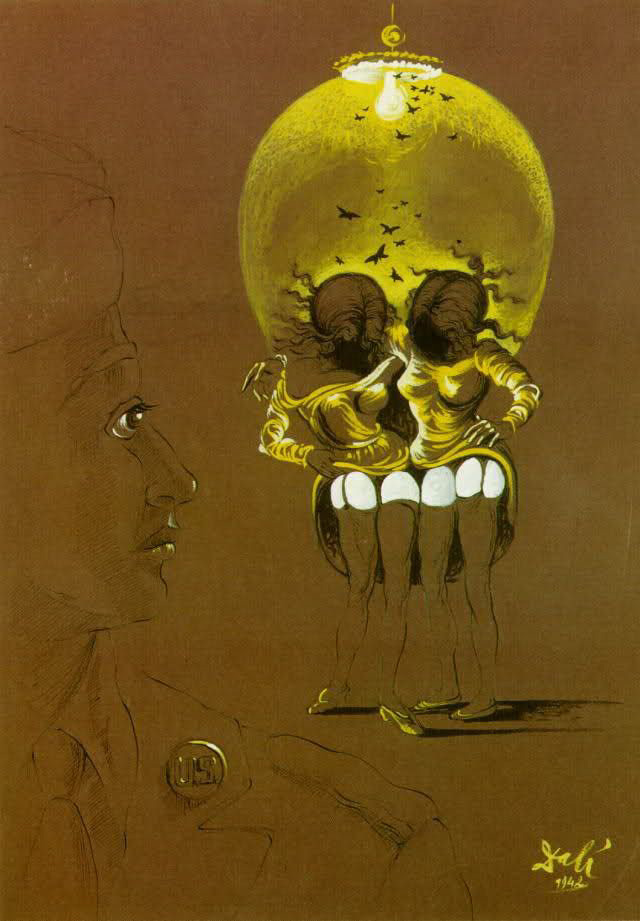

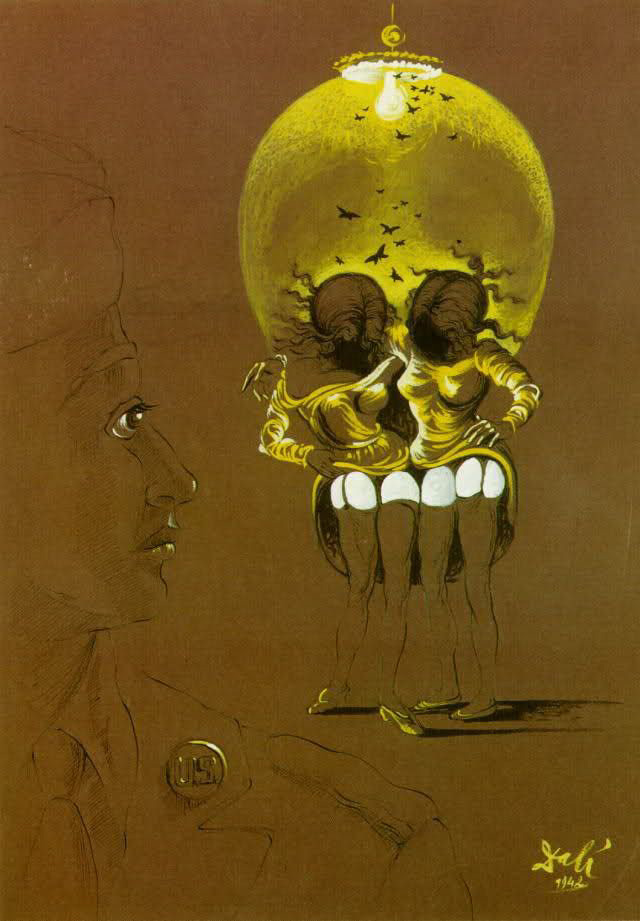

Public health posters were able to convey their designated horrors far more memorably before photos became the graphical norm. Take Salvador Dalí’s sketch (below) and final contribution (top) to the WWII-era anti-venereal disease campaign.

Which image would cause you to steer clear of the red light district, were you a young soldier on the make?

A portrait of a glum fellow soldier (“If I’d only known then…”)?

Or a grinning green death’s head, whose choppers double as the frankly exposed thighs of two faceless, loose-breasted ladies?

Created in 1941, Dalí’s nightmare vision eschewed the sort of manly, militaristic slogan that retroactively ramps up the kitsch value of its ilk. Its message is clear enough without:

Stick it in—we’ll bite it off!

(Thanks to blogger Rebecca M. Bender for pointing out the composition’s resemblance to the vagina dentata.)

As a feminist, I’m not crazy about depictions of women as pestilential, one-way deathtraps, but I concede that, in this instance, subverting the girlie pin up’s explicitly physical pleasures might well have had the desired effect on horny enlisted men.

A decade later Dalí would collaborate with photographer Philippe Halsman on “In Voluptas Mors,” stacking seven nude models like cheerleaders to form a peacetime skull that’s far less threatening to the male figure in the lower left corner (in this instance, the very dapper Dalí himself).

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

When Salvador Dali Met Sigmund Freud, and Changed Freud’s Mind About Surrealism (1938)

Destino: The Salvador Dalí — Walt Disney Animation That Took 57 Years to Complete

Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine.