People understand evolution in all sorts of different ways. We’ve all heard a variety of folk explanations of that all-important phenomenon, from “survival of the fittest” to “humans come from monkeys,” that run the spectrum from broadly correct to badly mangled. One less often heard but more elegant way to put it is that all species, living or extinct, share a common ancestor. This is true of evolution as Darwin knew it, and it could well be true of other forms of “evolution” outside the biological realm as well. Take languages, which we know full well have changed and split into different varieties over time: do they, too, all share a single ancestor?

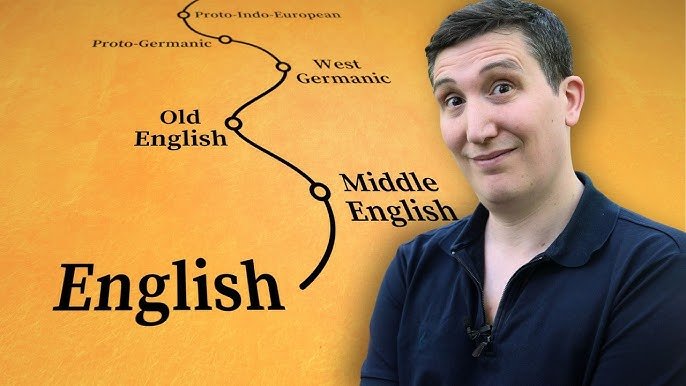

In the RobWords video above, language Youtuber Rob Watts starts with his native English and traces its roots back as far as possible. He ascends up the family tree past Low West German, past Proto-Germanic — “a language that was theoretically spoken by a single group of people who would eventually go on to become the Swedes, the Germans, the Dutch, the English, and more” — back to an ancestor of not just English and the Germanic languages, but almost all the European languages, as well as of Asian languages like Hindi, Pashtu, Kurdish, Farsi, and Bengali. Its name? Proto-Indo-European.

Watts quotes the eighteenth-century philologist Sir William Jones, who wrote that the ancient Asian language of Sanskrit has a structure “more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident.” As with such conspicuously shared traits observed in disparate species of plant or animal, no expert “could examine all three without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.”

The evidence is everywhere, if you pay attention to the sort of unexpected cognates and very-nearly-cognates Watts points out spanning geographically and temporally various languages. Take the English hundred, the Latin centum, the Ancient Greek hekaton, the Russian sto, and the Sanskrit Shatam; or the more deeply buried resemblances of English heart, the Latin cordis, the Russian serdce, and the sanskrit hrd. In some cases, linguists have actually used these commonalities to reverse-engineer Proto-Indo-European words, though always with the caveat that the whole thing “is a reconstructed language; it’s our best guess of what a common ancestral language could have been like.” Was there a still older language from which the non-Proto-Indo-European-descended languages also descended? That’s a question to push the linguistic imagination to its very limits.

Related content:

Was There a First Human Language?: Theories from the Enlightenment Through Noam Chomsky

How Languages Evolve: Explained in a Winning TED-Ed Animation

The Alphabet Explained: The Origin of Every Letter

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.