In the 1970s, the US began loosening restrictions on prison labor while simultaneously starting to attribute homelessness to mental illness and addiction (and ignoring economic factors). Forty-plus years later and those two parallel tracks of neoliberalism are merging and resurrecting the 19th century Victorian workhouse.

With the number of homeless continuing to rise in the US, municipalities, states, and the national government are faced with the task of doing something about a problem that’s apparently just too hard to solve. As with most any response to the fallout from neoliberalism here in the land of the free, the US comes equipped with a hammer in search of a nail that will profit the powerful and well-connected. And so it is with the “homeless problem” as we see the outlines of consensus beginning to form around solutions that involve incarceration — and therefore forced labor.

Charles Dickens’ “Oliver Twist” drew inspiration from England’s Poor Law Act of 1834, which established the workhouse system that rather than provide refuge for the elderly, sick and poor or food and shelter in exchange for work in times of high unemployment, established a labor prison system.

And so it goes in America 190 years later.

US prisons that for decades have used forced labor will increasingly include the homeless among their ranks as the US Supreme Court-sanctioned criminalization of homelessness gathers momentum, and states like California return to “tough on crime” policies with the stated goal of ridding the streets of the unhoused.

The criminalization of homelessness is an easy solution that means the fact we have turned a basic human necessity over to market forces goes unchallenged. That means doing nothing about:

- Poverty wages (between 40-60 percent of the homeless are employed).

- Housing cartels jacking up rent.

- Homebuilder cartels constraining supply.

- Private equity buying up single-family and multi-family housing, which means a lack of affordable housing.

- Central bank monetary policies that make the rich richer while mostly hurting everyone else.

- A healthcare system that frequently bankrupts people.

- A lack of a social safety net.

By deflecting attention away from these issues while simultaneously expanding the reach of the carceral state — which weakens “free” labor — the criminalization of homelessness is a win-win for American plutocrats.

No Effort to Stop the Causes of Homelessness

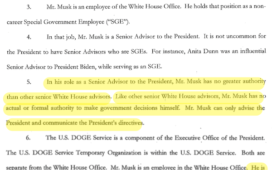

Trump is the latest to come along with a plan that does nothing to address the underlying causes.

“For a small fraction of what we spend upon Ukraine, we could take care of every homeless veteran in America,” he says in a 2023 video. He’s partially right. The US could take care of every homeless individual for a fraction of the money that’s been spent on the Ukraine racket. Here’s more:

…[Trump] will open large parcels of inexpensive land, bring in doctors, psychiatrists, social workers, and drug rehab specialists, and create tent cities where the homeless can be relocated and their problems identified.

In addition, President Trump will bring back mental institutions to house and rehabilitate those who are severely mentally ill or dangerously deranged with the goal of reintegrating them back into society.

We’ll see if he follows through. Plans to deal with the homelessness crisis are often unveiled and quickly forgotten, and Trump has a short attention span. Nevertheless, it’s hard to argue this is worse than the whole lot of nothing currently being done; it’s also easy to see it going horribly wrong (e.g., an understaffed site that’s inexpensive because it’s on toxic land which quickly devolves into chaos and mass arrests).

Also, “relocated” to where? Trump is light on details, but If there’s no public housing and no affordable housing, where are people to go?

“Problems identified.” What if the problem is lack of money as many of the homeless are working.

Rather than answer these basic questions, he swings for the deportation pinata. Trump also says any failure to comply will result in imprisonment, which is now a bipartisan solution.

The Criminalization of Homelessness

Let’s take a look at California. That great bastion of liberalism contains one-third of the nation’s 650,000-plus homeless, and its champion, Gov. Gavin Newsom, is largely in agreement with Trump. He signed an executive order in July calling for cities to “humanely remove encampments from public spaces.” The order of course does nothing to address the systemic problems behind homelessness, including a lack of affordable housing and Social Security benefits not coming close to covering rent leading to skyrocketing numbers of homeless senior citizens. How “humane” can Newsom’s policy be?

As Deyanira Nevárez Martínez, an assistant professor of urban and regional planning at Michigan State University writes, Newsom’s approach effectively turns the issue over to the criminal justice system and “leads to forced displacement that makes people without housing more likely to be arrested and experience increased instability and trauma.”

And it won’t just be displacement. California localities, like so many across the country, are increasingly passing laws that make it a crime to be unhoused.

The Supreme Court ruled this year in Grants Pass v. Johnson that cities can penalize individuals for sleeping in public spaces even when no shelter is available. That decision overturned the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling that anti-camping ordinances violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

California voters are once again getting “tough on crime.”

On election day California voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 36, which increases penalties for theft and drug possession, including reclassifying some misdemeanors as felonies. The measure was sold as a way to put an end to homelessness and included pro-business PACs and the powerful California Correctional Peace Officers Association as its major backers. Property crimes did indeed increase during the initial years of the pandemic, but have since begun to decline again across California, which continues a decades-long trend, according to the Department of Justice. Nonetheless, California police, prosecutors, and Silicon Valley “bros” have for years pushed the asinine argument that the state’s supposedly soft-on-crime approach is the cause behind the increase in homelessness.

When homelessness is framed as a choice that takes advantage of too-lenient laws, the solution is easy: lock them up. And that’s what California’s new laws will do. From Cal Matters:

The Legislative Analyst’s Office forecasts that the measure will cost tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Those costs are chiefly from placing a few thousand more people in prison and putting them in for longer terms.

A few notes on drug addiction and untreated mental health issues, which are often blamed for the modern day Hoovervilles across the country.

A study from UCSF’s Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative last year was one of the deepest dives into California’s crisis in decades. It found that drug use and mental health problems are not the driver behind people losing housing; the primary reason is the increasing precariousness of the working poor.

Even if you believe that the issue can be boiled down to mental health and drugs, that is even more of a reason to attack the underlying economic culprits behind homelessness and poverty in the US. That’s because mental health and/or addiction problems can result from the loss of housing and it can severely worsen existing issues.

The UCSF study found that many succumb to drugs as a way to numb the pain of being chewed up and discarded by American society. It is also well-established that poverty and homelessness can lead to or worsen physical and mental health. For example, studies have shown PTSD is common after losing one’s home. It goes beyond just homelessness. For example, a recent study published in the Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing finds that food insecurity is linked to severe mental illness. About 1 in 5 children in the US face food insecurity, as do 44 million Americans overall.

Back to California. While Proposition 36 also creates a new category of crime — a “treatment-mandated felony” — which allows for the completion of drug treatment instead of going to prison, the accused still face up to three years behind bars if they don’t finish treatment, and there are major questions about funding. Newsom says the measure is likely to “impact some existing drug treatment and mental health services.” It will also shift more of those services under the umbrella of the criminal justice system, which frequently makes the problem worse as we’ve seen from the decades-long “war on drugs.” As the Prison Policy Initiative explains:

Jails and prisons are often described as de facto mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, and corrections officials increasingly frame their missions around offering healthcare. But the reality is quite the opposite: people with serious health needs are warehoused with severely inadequate healthcare and limited treatment options. Instead, jails and prisons rely heavily on punishment, while the most effective and evidence-based forms of healthcare are often the least available.

This unsurprisingly results in an endless cycle of arrest for people who use drugs and for those who are homeless. The UCSF study found that roughly 20 percent of the state’s unhoused population entered homelessness from an institutional setting, such as jail and prison stays. And criminalization only makes the problem worse. From Governing:

The collateral consequences of even short-term jailing — such as loss of employment, separation from families, and fines and fees — increase the likelihood of future arrest while exposing arrested individuals to health risks and unsanitary conditions associated with jails.

Again, this measure and other California efforts blame drug use and crime for homelessness and do nothing to address the primary causes, i.e., unchecked American capitalism.

Time and again those experienced in the field say the most effective method to combat the crisis is to stop people from becoming homeless in the first place. California is not only ignoring that plea, but is making the problem even worse.

Slave Labor and American Productivity

What else did citizens on the “Left Coast” vote for? They rejected a rent control ballot measure that would have given cities more freedom to limit how much landlords can raise rent. Opponents of the measure included landlords, realtors, and Newsom who argued that rent control would reduce incentives to build new housing. He didn’t comment on any incentives to not build more housing.

Voters also rejected a prison reform measure that would have ended forced labor in prisons and jails. From Cal Matters:

California mandates tens of thousands of incarcerated people to work at jobs – many of which they do not choose — ranging from packaging nuts to doing dishes, to making license plates, sanitizer and furniture for less than 74 cents an hour, according to legislative summaries of prison work.

This is common practice across the country where imprisoned laborers have no minimum wage, no overtime, no unemployment, no workers’ compensation, no social security, no occupational health and safety protections, and no right to form unions and collectively bargain.

For decades the US has been moving towards removing restrictions on prisoner work and expanding the system — even if it puts forced labor in competition with “free” labor.

Back in 1929 the Supreme Court upheld a law that restricted the interstate sales of prisoner-produced goods, explaining that “free labor, properly compensated, cannot compete successfully with the enforced and unpaid or underpaid convict labor of the prison.”

That began to change in the 1970s, however, as neoliberalism took hold, Congress started to ease restrictions on private companies using prison labor. They were allowed to use it, but required to pay prevailing wages, most of which can be diverted to fund prisoners own imprisonment or otherwise stolen.

Similar neoliberal trends were happening on the homelessness front:

In my upcoming book, I show that, beginning in the 1980s, attributing homelessness to mental illness and addiction was politically engineered to obscure the socioeconomic roots of the crisis and to justify the removal of homeless people from public space.https://t.co/K8FH27HUET pic.twitter.com/nLJoExurH6

— Brian Goldstone (@brian_goldstone) December 11, 2024

Here’s Erin Hatton, professor of sociology at the State University of New York at Buffalo with some numbers showing where the situation is today:

In the United States today, more than 2 million people are incarcerated in prisons and jails, another 4.5 million people are under supervision via probation or parole, and 70 million people have some type of criminal record. The carceral state has thus exerted its grip on nearly half of the U.S. workforce. In fact, the combined prison and jail population of the United States roughly equals the number of employees that Walmart, the world’s largest employer, employs across the globe.

Hatton breaks the types of jobs in US prisons and their effects on “free” labor:

The first category is facility maintenance, also known as “regular” or “non-industry” jobs. In these roles, incarcerated people work to keep the prison running; they sustain its operations. The vast majority of incarcerated workers perform this type of labor…Because wages for this work are invariably minimal—ranging from no pay at all in many southern states to $2 per hour in Minnesota and New Jersey—this form of labor saves prison operators untold sums of money by supplanting free-world, full-wage workers.

The second category is “industry” jobs, which are positions in the government-run prison factories that were launched in the 1930s. These account for just under five percent of state and federal prisoner employment. People who labor in these factories produce a wide range of goods and services for sale to government agencies: office furniture and filing cabinets; road signs and license plates; uniforms, linens, and mattresses for prisons and hospitals; wooden benches and metal grills for public parks; even body armor for military and police. In Texas, Georgia, and Arkansas state prisons, incarcerated workers receive no wages for this labor. On average, state and federal prisoners earn $0.33–$1.41 per hour for this work (as compared to an average of $0.14–$0.63 per hour for the facility maintenance jobs described above).

The third category of incarcerated labor is for private-sector companies that set up shop inside U.S. prisons. Such jobs employ just 0.3 percent of the U.S. prison population. These are the highest paid prison jobs, because private-sector companies are legally obligated to pay “prevailing wages” in order to avoid undercutting non-prison labor. However, incarcerated workers do not actually receive these “prevailing wages.” Private employers often pay only the minimum wage, not the prevailing wage, and legal loopholes allow them to pay even less. Moreover, incarcerated workers’ wages are subject to many deductions and fees, which are capped at a whopping 80 percent of gross earnings. In other words, U.S. prisons seize most of the workers’ wages in these jobs. Further, some states have mandatory savings programs that take away an additional portion of the pay. Thus, even though regulations mandate free-world compensation for private-sector jobs in prison, prison rates prevail.

The final category is work that occurs outside of the prison, through various labor arrangements such as work-release programs, outside work crews, and work camps. While no concrete data are available, reports suggest that such jobs are more common than both public and private industry jobs, though not as common as facility maintenance jobs. This category is highly heterogeneous, including work for public works, nonprofit agencies, and private companies. In work-release programs, prisoners typically maintain free-world jobs—at free-world wages, though subject to prison-world deductions—and then return to the prison after work hours. In prison work crews, incarcerated workers leave the prison or jail facility during work hours to perform public works, or “community service” jobs, such as fighting fires and cleaning highways, park grounds, and abandoned lots. Such workers typically return to prison at the end of the workday, unless their labor—as in the case of wildfires—is far from the prison; in those cases, they are typically housed in prison-like facilities, such as fire camps. In one instance, incarcerated women who labored for a multi-million dollar egg farm in Arizona were relocated to company housing so that the farm could retain its low-wage and reportedly “more compliant” incarcerated labor force despite the COVID-19 lockdowns that would halt the prison’s work-release program.

Prison labor is a nice little gift for American corporations. According to a 2022 report from the ACLU, “labor tied specifically to goods and services produced through state prison industries brought in more than $2 billion in 2021.”

Details are less readily available about American jails and other forms of “supervision” and their benefits for capital. The ACLU report did not account for work-release and other programs run through local jails, detention and immigration centers and even drug and alcohol rehabilitation facilities. But we can gather some anecdotal data. According to the AP:

Some people arrested in Alabama are put to work even before they’ve been convicted. An unusual work-release program accepts pre-trial defendants, allowing them to avoid jail while earning bond money. But with multiple fees deducted from their salaries, that can take time.

And in Louisiana:

Jack Strain, a former longtime sheriff in the state’s St. Tammany Parish, pleaded guilty in 2021 in a scheme involving the privatization of a work-release program in which nearly $1.4 million was taken in and steered to Strain, close associates and family members. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison, which came on top of four consecutive life sentences for a broader sex scandal linked to that same program.

The Capitalist Dream of Incarcerated Laborers

Gurner Group founder Tim Gurner’s comments last year calling for a 40-50 percent rise in unemployment and “pain” in the economy to remind laborers that “they work for the employer, not the other way around” were refreshing for their honesty.

Gurner Group founder Tim Gurner tells the Financial Review Property Summit workers have become “arrogant” since COVID and “We’ve got to kill that attitude.” https://t.co/lcX3CCxGuj pic.twitter.com/f9HK2YZRRE

— Financial Review (@FinancialReview) September 12, 2023

Gurner might be an Australian “apartment wunderkind,” but such beliefs aren’t confined to the Lucky Country. Indeed, such forms of coercion are precisely what capital likes about imprisoned workers. From Hatton’s Coerced: Work Under Threat of Punishment:

….the defining feature across all these forms of prison labor is the infliction of punishment, or the threat of punishment, to secure compliance. When incarcerated workers do not obey a command from the corrections officers who oversee their labor, they can be fined a week’s wages, put on “keeplock” (confined to one’s own cell), and put in solitary confinement. Because of these punishments, moreover, incarcerated people can lose opportunities for parole. The risks of noncompliance for incarcerated workers thus include losing crucial connections with friends and family, losing access to essential food, amenities, recreation, and freedom of movement (however constrained), and, for some, losing the possibility of future freedom.

The following is from the Urban Institute in 2003, but as Gurner’s comments demonstrate, there’s little reason to suspect such opinions have changed:

Employers strongly spoke of the quality of the inmate workforce in responses to the question of what they liked best about employing inmates. Responses of workforce “quality and productivity” far outweighed “lower costs” 53% to 7%. Additionally, employers rated inmates as somewhat more productive than a domestic workforce might be, and 92% said they “recommend” the inmate workforce to business associates. As one employer explains: “Inmates learn that the success of our company depends on the satisfaction of our customers with our product. Quality, service and price have to meet expectations. Our futures are intertwined…”

This data provides supporting evidence that in today’s environment, employers consider inmate workers to be productive workers—“more productive” than the domestic workforce— in a variety of manufacturing, assembly and services production settings.

Yes it would make sense they’re more productive. Less distractions.

Perhaps the ever-expanding US carceral plays an underappreciated role in America’s “productivity boom”:

Just how much does the US rely on prison labor?

The American economy pic.twitter.com/CHHOHDBFq7

— inhumans of capitalism (Ojibwa )🔻 (@Inhumansoflate1) October 27, 2024

He might be slightly overstating the case out of self interest but not by much. Imprisoned Arizonans, like most people on the outside, are forced to sell their labor for at least 40 hours a week. Many of the ones in official captivity earn just 10 cents an hour for their work, however.

Arizona, like many states, contracts with The GEO Group, one of the largest private prison companies. If that name sounds familiar, that’s because it was in the news recently due to its stock soaring following Trump’s victory and his promise to crack down on crime and illegal immigration.

The details of the contracts a state like Arizona signs with The GEO Group are telling. At Florence West prison, for example, Arizona guarantees GEO a 90% occupancy rate. The state must pay a per diem rate for 675 prisoners, regardless of how many people are actually incarcerated there, although the state is incentivized to make sure it’s at or near capacity. That’s because, as Arizona Department of Corrections Director David Shinn explains, prisoners are forced to provide labor “to city, county, local jurisdictions, that simply can’t be quantified at a rate that most jurisdictions could ever afford. If you were to remove these folks from that equation, things would collapse in many of your counties, for your constituents.”

So what amounts to slave labor helps keep taxes low on one end. And then there’s the profit motive on the other, as explained by Arizona Rep. John Kavanagh:

“You have to guarantee that they’re going to have people there, and they’re going to have a profit that they make, they’re going to have income,” Kavanagh said. “No one’s going to enter into a contract when you can’t guarantee the income that they expect. That’s kind of based on basic business.”

“Basic business” also includes the widespread availability of low-wage and easily exploitable immigrants for American capital, which brings us back to Team Trump and The GEO Group.

Will Trump deal with illegal immigration by making it difficult for these migrants to get paid work or will he provide more of an “innovative” testing ground for Israeli-style surveillance and detention tech while continuing to ensure the supply of cheap labor? It increasingly looks like the latter.

According to incoming vice president JD Vance, the Trump administration is going to ensure its immigration and deportation plans are not bad for business. “Generally I agree, okay, we’re going to let some immigrants in,” he says. “We want them to be high-talent, high quality people. You don’t want to let a large number of illegal aliens in.”

The Trump plan is starting to sound like policy as usual, which highlights the connection between the police state, immigration detention, deportation, and labor. From Noah Zatz, a law professor at UCLA:

This continuity is particularly important because labor advocates and the labor movement have come to understand—through a long and still-contested process—how employers gain power to intimidate, retaliate against, and divide workers when the state’s deportation threat hangs over them and can be invoked by employers.

Better Solutions to Homelessness

The US is actually finding success cutting the number of homeless veterans. The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) announced in November that veteran homelessness rates dropped to a record low since detailed counting began in 2009. Officials counted 32,882 homeless veterans, down significantly from recent years and a 55.6 percent decrease from 2010.

While the overall number is still soberingly high, and the program is imperfect since it doesn’t address underlying economic causes that will continue to see vets cast onto the streets, it is progress. How did they do it?

Using a Housing First approach, which prioritizes getting a homeless individual into housing and then assists with access to health care and other support. Notably, the VA program does not try to determine who is “housing ready” or demand mental health or addiction treatment prior to housing. The Housing First model says that housing is a fundamental right and that housing programs should identify and address the needs of the people it serves from the people’s perspective. The VA is doing that by providing immediate access to permanent, subsidized, independent housing without treatment participation or sobriety prerequisites.

For this fiscal year—Oct. 1, 2024, to Sept. 30, 2025—the VA budget for Veteran homelessness programs is $3.2 billion. That’s less than what the US has been spending per month on Ukraine since Feb. 2022.

So why not scale up the VA program and apply to all homeless Americans, as well as help those in danger of becoming homeless. According to Fran Quigley who directs the Health and Human Rights Clinic at Indiana University McKinney School of Law, there are nine million U.S. households that are behind on their rent right now. There’s an easy way to help them: give them money.

If we consider capital’s incentives to discipline and control workers — including throwing the homeless into modern day workhouses — there is a strong argument to be made for fledgling American organized labor to more actively join the fight against both homelessness and mass imprisonment. As Zatz from the UCLA School of Law argues:

One intuitive answer focuses on characterizing incarcerated people as workers and the carceral state as a system of labor exploitation. This approach asserts a shared identity and a shared foe. The easiest way to make the argument highlights how employers may substitute hyper-vulnerable incarcerated workers for rights-bearing “free labor.” But the strategy has been known to backfire: Rather than engendering solidarity, it can instead amplify hostility by portraying incarcerated people as a threat to non-incarcerated people’s jobs.

A different path to solidarity highlights how the carceral state reaches into the heart of so-called “free” labor markets. What I call a “carceral labor continuum” stretches from the prison, through “work-release” programs, to parole work requirements, to “working off” criminal fines and fees, and more. As a result, carceral labor is not a problem confined to the prison, and it provides no neat divide between any “us” and “them.”

Or as the Hampton Institute puts it:

labor-based consumer income. There will be many contradictions that come with keeping capitalism alive for the sole purpose of feeding the soon-to-be trillionaire class. Of course, this is all contingent on the outcome of class struggle.

— Hampton Institute (@HamptonThink) September 20, 2024