It seems like a funny question to ask given Russian government debt to GDP isn’t that large. Craig Kennedy argues that taking into account forced bank lending means that (contingent) government liabilities are much larger than conventionally-defined public liabilities (report here). The summary:

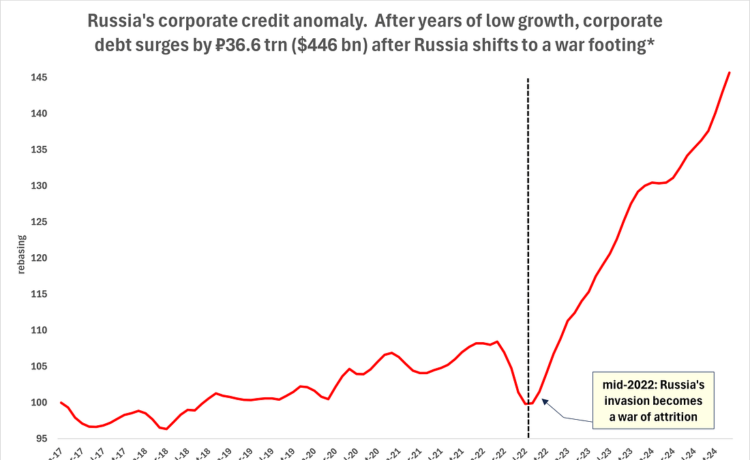

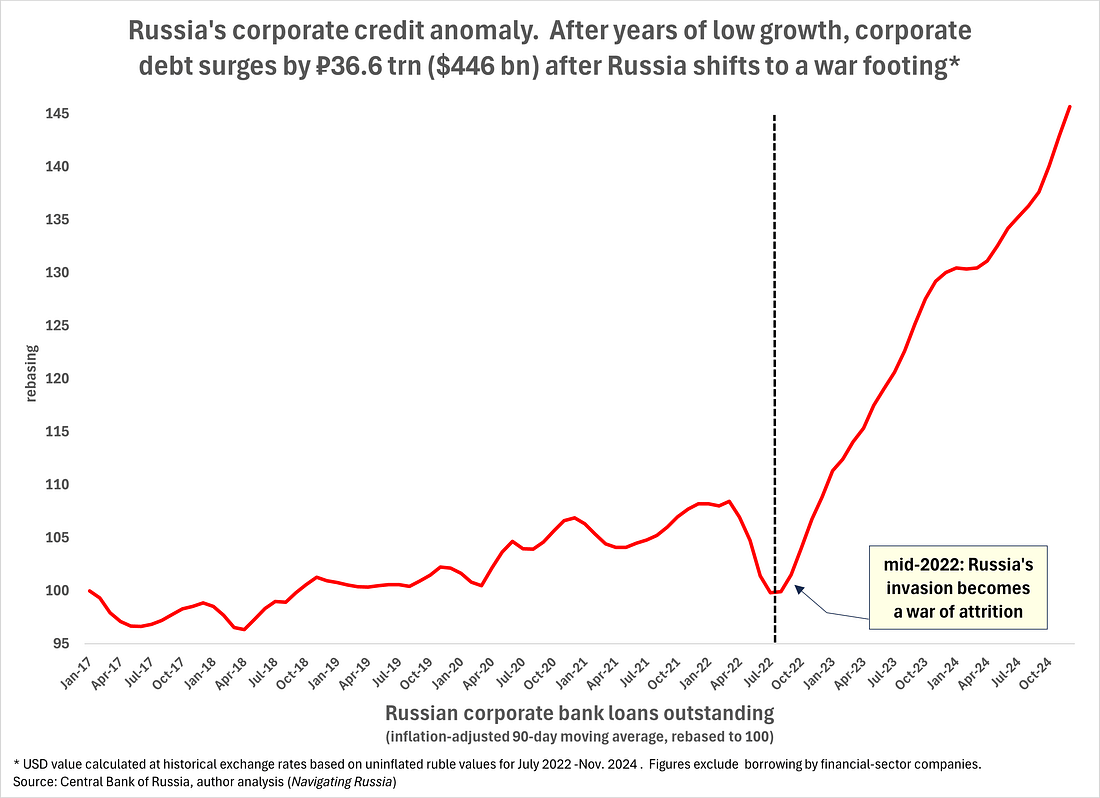

Moscow has been stealthily pursuing a dual-track strategy to fund its mounting war costs. One track consists of Russia’s highly scrutinized defense budget, which analysts have routinely deemed “surprisingly resilient.” The second track—largely overlooked until now—consists of a low-profile, off-budget financing scheme that appears to make up a major portion of Russia’s overall war expenditures. Under legislation enacted in February 2022, the state has taken control of war-related lending at Russia’s major banks. It is directing them to extend preferential loans—on terms set by the state—to a wide range of businesses providing goods and services for the war. Since mid-2022, this state-directed war-funding scheme has helped drive a large part of Russia’s anomalous ₽36.6 trn ($446 bln) surge in overall corporate borrowing.

Initially, this off-budget war-funding scheme proved advantageous to Moscow by helping limit defense spending in the budget to levels that are easily managed. That misled budget-watchers into concluding—incorrectly as it turns out—that Moscow faces no serious risks to its ability to sustain funding for its war on Ukraine. More recently, however, Moscow’s heavy reliance on state-directed preferential lending has begun to cause serious, adverse consequences at home. It has become the main driver of Russia’s 10% inflation and has sent the Central Bank’s key rate to a record 21%.

More broadly, Russia’s off-budget war debt is significantly elevating systemic credit risk, both for the near- and medium-term. High interest rates are driving up corporate distress levels in the “real” economy and raising fears of widespread bankruptcies. The Central Bank has voiced concern over “aggressive” lending and inadequate capital buffers in the banking industry. What’s more, the state has now saddled the banks with large amounts of problematic, corporate war loans. Many could turn toxic once the shooting stops and defense contracts get cancelled. Worse still, relaxed oversight rules on defense-related loans mean bank regulators might not see these problems arising until it’s too late.

By late 2024, the Kremlin had been briefed on these rising risks and warned that change is needed. This poses a dilemma for Putin: continue relying on off-budget debt, and you further increase the risk of cascading credit events that undermine Russia’s image of “surprising resilience” and weaken its negotiating leverage. The alternatives: a major increase in the budget deficit—with the bad optics that entails—or a sharp reduction in spending on the war. This may explain Putin’s recent complaint to his generals that they can’t “keep pumping up spending to infinity.”

These new developments are likely to affect Moscow’s war calculus in two ways:

- Moscow will be less inclined to believe time is on its side—the longer it must fund elevated war costs, the greater the risk of escalating credit events;

- Moscow will prioritize sanctions relief aimed at boosting cashflows to help with politically perilous post-war debt restructuring and rearmament. Concessions that would provide the greatest cashflow relief include (i) an easing of oil sanctions, (ii) the resumption of pipeline gas deliveries to Europe and (iii) the unfreezing of Russia’s wealth fund.

Given Russia’s financial challenges, maintaining these constraints on Russia’s cashflows insures Ukraine and its allies retain substantial leverage. If kept in place past a ceasefire, they could be instrumental in securing a final, comprehensive peace settlement—including reparations.

Kennedy presents this picture of corporate borrowing to buttress his argument. See the entire report here.

Source: Kennedy (2025).