The history of different peoples, and of humanity as a whole, can be presented in all kinds of ways. But, in the end it comes down to food and hunger. In the final analysis, it’s the stomach that counts.

I am in possession of a protruding middle. If you don’t look carefully, you might miss it but it’s there: rotund, firmly planted and bulging. I carry it before me as if it were something to be proud of. On the occasions when it looks less prominent, it can be hidden under loose and preferably dark clothing, but if I happen to catch sight of my profile in a full-length mirror the curving protuberance is very much in evidence. It starts just under the ribcage and ends somewhere around the waist.

Excess weight cannot be easily concealed: last year, my average was 102 kilos. This was a year in which I committed myself to some serious dieting over a period of several months, and even managed to cross that closely guarded border between obesity and stoutness. I returned from this excursion only recently. Generally, I fall into the category of class 1 obesity, although there have been times when I’ve slipped into class 2. This happened once when I was dumped by a girlfriend (oh, hi there!). She couldn’t endure the fact that I didn’t look after myself properly, or so she told a mutual friend. Personally, I think she was exaggerating – my pot-belly doesn’t interfere with much. I can run for the tram easily enough and carry heavy luggage up to the 5th floor if I need to. I have a job in the arts, I make public appearances, I socialize. It’s a regular sort of life. The only issue is that I have a paunch.

I like to eat, true. You know the guy who wolfs down all the nuts as they get passed around with the beer and then picks out the last bits and the grains of salt? That’s me. Not that I don’t believe in sharing but, given half a chance, I’ll polish off the leftovers. See that last potato pancake which should be left as an offering to the gods of abstinence and self-restraint? Anyone still hungry? No? OK, I’ll have it then. Pity to see good food wasted. I know people notice, of course I do, even though they try hard not to show it. And I truly admire those who leave food on their plates because they’ve had enough, or they don’t like the taste, or because they want to leave room for dessert. Such nobility of spirit!

Vegetables don’t help either. I’ve been vegan for a full eight years but paunch-wise little has changed. In the beginning, veganism served me well as crowning evidence in those endless silly conversations with family and friends. ‘Are you sure a salad will be enough?’ Just watch me.

I’ve always felt irritated by those brightly illustrated articles that try to persuade you into veganism because it’s so great for wellness and health – as if not eating animals wasn’t argument enough. But I’m used to it and, in any case, these days the divide lies elsewhere. Think of it as the gulf between that long file of sporty types waiting to buy a low-calorie fruit sorbet on the first hot day of the year, and the considerably shorter line of people beside them queuing for a bag of chips.

I know where I’d be standing. Remember those posters displayed at bus stops with the words ‘Go on, binge!’ and the image of a sausage that looks like a time-bomb? The organizers of the campaign were flooded with criticism and, obviously, I stood with the critics. The poster was harmful, sure. It was classic, counterproductive fat-shaming. But at heart, under all those layers of adipose tissue, in the corners of my consciousness which I prefer, mostly, not to share – at least not spontaneously – I suspected that the advocates behind the image were right. It needs to be said straight: I am fat. And whose fault is that, if not mine?

This isn’t an uncommon way of thinking. According to research done in 2014 most people who are either overweight or obese blame the problem on their own behaviour (86.7%), their diet and eating habits (83.3%), or their genes (63.3%). I know the gene mantra well: it’s in our blood, it’s in the family, it’s to do with being strong and well-built.

‘Have you got a weight problem too, son?’ an alcoholic father writes to his massively large offspring in George Saunders’ short story, ‘The 400-pound CEO’. ‘I realized all of a sudden, and now I’m big as a house. Take care, it might be in our genes.’ Saunders specializes in writing about life’s losers and we know that the reference to genes is just a cheap excuse. Not only is he obese, he’s deluded.

It may be my genes, but more likely it’s the fact that I snack. I can’t resist a desert, I’ll have that extra canapé for supper – can’t do me any harm – and, since it’s dark chocolate I’m looking at, I might as well help myself to three pieces at once. (I no longer buy the sort filled with nut paste, don’t even ask.) Is anyone forcing me? None that I can see.

I spent a long time imagining it was me. After all, as a child I was skinny. I remember the family wringing their hands and lamenting that I was all skin and bones. You could count my ribs. So, I guess this thing must have happened later, after I left home. Though I began to have my doubts when, in my first year at university, I ran into a hockey trainer I hadn’t seen for years. I’d been a goalie in his team at the age of seven, so I got him talking and reminded him who I was. He stared at me for a while and then said, very cheerfully: ‘Oh, right! You were the slightly podgy one, weren’t you?’

When I was clearing my mother’s flat after she died, I found a Year 1 report with a comment, written in that sweeping scrawl characteristic of the medical profession: ‘More dietary fruit and vegetables recommended’. But things have moved on since my mother and my grandmother passed, I suppose, and maybe the older I am, the easier it is to admit that not everything depends on me.

I’m reminded of the American feminist Roxane Gay, who is ranked ‘the best’ by Yazz, the youngest heroine in Bernadine Evaristo’s novel Girl, Woman, Other. I should be careful in drawing any analogy, though, because our problems are of a different calibre. Gay writes:

‘For so long I’ve never talked about this. I supposed we should keep our shames to ourselves.

…

But I’m sick of this shame. Silence hasn’t worked that well. Or maybe this is someone else’s shame and I’m just being forced into carrying it.’

In her book Hunger, Gay describes how, in her teens, she was raped by her boyfriend and his chums. For years afterwards she ate compulsively, thinking that ‘if my body became repulsive, I could keep men away’.

My own story is nowhere near as serious, and my weight-associated troubles are not half as overwhelming as those Roxane Gay has endured. What’s more, I am a man, and men with paunches have it easier than women with a similar issue. But the thing we both share may be an urge to get a grip on the shame we struggle with daily, an impulse to examine it in the cold light of day, and check for a hidden logo that might identify some kind of manufacturer to whom we could return this flawed and useless aspect of ourselves.

It might also mean we share a degree of compassion for each other. Rather like the waitress in Raymond Carver’s story ‘Fat’, about a man who walks into a bar and eats, and eats, and eats. When the waitress’ boyfriend, the cook, makes a jokey remark about their portly customer, she responds indulgently: ‘Rudy, he is fat… but that is not the whole story’.

Hanka

‘Until I started gaining weight, I had a healthy attitude towards food,’ Roxane Gay writes. ‘My mother is not a woman with a passion for cooking, but she has an intense passion for her family. Throughout my childhood she prepared healthy, well-rounded meals for us, which we ate together at the dinner table. There were no rushed dinners sitting in front of the television or standing at the kitchen counter.’

I cannot say the same about Hanka. It wasn’t that my mother was indifferent to her children, she simply showed her love in other ways – not through cooking and certainly not by serving up balanced, healthy meals for a family seated around the dinner table. Hanka’s cooking was more about feeding the masses. She would provide a huge saucepan of hunter’s stew made with fresh and pickled cabbage, a few mushrooms, some sausage, a jar of tomato purée, and some spices. There was so much of it in the pot that we had to use both hands for stirring, to prevent her concoction from burning. Or there’d be a stack of thickly breaded chicken breast cutlets.

When Hanka launched into preparing these, she’d make a cartload for her three children and herself, enough to last for days, maybe forever, so she’d never have to cook again because, truth be told, she hated it. She had enough to do just going out to work. Running the household was simply too much and no wonder – she was bringing up a family on her own. And there were never enough chicken cutlets. We’d eat them all in a single sitting.

We ate in front of the telly. I remember our Sunday screenings with particular fondness, though they took a degree of preparation. First, I would run over to the shop for some ‘French’ bread rolls (3-4 simulated baguettes) which Hanka then made into canapés stacked with cheese, cured meat, radish and chives. Or she’d use plain liver sausage. Each of us had a huge plate with a mound of these canapés, which we’d stuff into our mouths without so much as a glance.

But our staple diet was potatoes: boiled, fried, mashed, re-fried, mixed with flour and re-boiled, hot potatoes, cold potatoes – dishes fit for a king. But, above all, we loved potatoes served in their most perfect form, Western-style. I’m talking chips. There was a bit of work involved, certainly. The spuds had to be peeled and chopped, and then you stood over a stove smoking with boiling oil. But it felt like a holiday, and the massive bowl of fries per head we all got at the end was a meal in itself.

Hanka wasn’t like Roxane Gay’s mother. She was no Pomona, no goddess of fruitful abundance and plenty ‘spilling from her basket the colourful beauty of the sun’, as in Bruno Schulz’s ‘The Street of Crocodiles’(translated into English by Celina Wieniewska). Mum was more of a Penelope from Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other who

‘loved the feeling of being absolutely stuffed after a meal / When her stomach was bloated, ready to burst / Otherwise she felt an emotional vacuum’.

I must have made it clear by now that Hanka was pretty large. Sure, she experienced different phases of obesity, leaner years and fatter years, though I only remember the fatter period, the times before chemotherapy succeeded in slimming her down so effectively – but that was pretty brief. My guess is she did her best to fill her stomach so as to chase away the feeling of emptiness pushing up from her viscera which, if not controlled in time, rose to tighten in her throat. I have no difficulty visualizing this, I often experience it myself.

The inner hollowness Hanka experienced might have been a metaphor for her life’s failures: an unsuccessful career in sport, a broken heart, a difficult relationship with her mother. But it was also entirely literal. It expressed the emptiness of Mum’s purse, for she had been left alone with three children at a time when the Polish state socialism was collapsing. The new order had barely been born, but it was already full of ideas about how to organize people’s lives. No surprise, then, that it made one or two errors on the way. At home there were often loud shouts, demanding to know who’d eaten the cutlets or drunk all the milk. ‘Not me!’ was the first calculated lie I learnt to tell. For much of my life, I imagined this was perfectly normal. I’ve come to understand what it was really about only recently, looking back: this was poverty.

Obviously, at the time, we never thought of ourselves in those terms. Other people were poor. The neighbours living on the floor below – they were poor. This kind of rationalization is not uncommon. Take a recent post from Agata Diduszko-Ziglewska, for example: ‘It was only as an adult that I realized that I’d been a disadvantaged child from an impoverished household.’ But was I starving? That’s just it: I wasn’t. Hanka’s cooking was all about finding the cheapest and most effective way of assuaging hunger. The balance between satiety and cost was her prime concern.

This might serve as the answer to that great, bulbous riddle that is my paunch. Poverty, the economic transition, bad eating habits shaped by food scarcities in the Polish People’s Republic, combined with even worse habits encouraged by capitalism run wild. Yes, Hanka was fat and she brought up three fat children, Rudy, but that is not the whole story.

Albina

From late spring and throughout the summer, we transported kilos and kilos of fruit and veg from the allotment: green beans, new potatoes, peas, cabbage, field cucumbers, raspberries, strawberries. Towards the end of the summer there was a frenzy of preserving, jaring and bottling. We pickled cucumbers, poured sweet syrup over the strawberries and raspberries, we picked mushrooms (though, as activities went, that was rarer). The daily routine consisted of peeling potatoes, frying up the meat, grating apples and carrots for the salad, stewing the fruit, and heating up the meat broth. In the afternoons there were tiny oat and chocolate cookies or mini meringues to be baked. And then there was the shopping: homogenized cheeses, small wheel-shaped pastries for the grandchildren, cakes to have with coffee, tinned tangerines in case the home-preserved strawberries and raspberries ran out. Albina’s life was centred entirely around food.

In our relatively small, three generation family, our grandmother, Albina, was mistress of the kitchen. Her cooking was far from sophisticated, but it was healthy, simple and nutritious – or so we thought at the time. Yet when I remember the meals she prepared, I see above all a large, tempting, glistening splash of yellow fat. It seemed to cover everything. The portions she offered were never large, but the provision of food was continuous and unbroken. Even when no one could manage any more, Albina would slip a further round of specialities onto the table, and tended to get grumpy if they were left untouched. Our grandmother’s love was expressed entirely through food.

And no wonder. She was one of ten children, born in the 1920s in a small village halfway between Oświecim and Kęty. Her birth mother was most probably an orphan, and Albina lost her when she was very young. Over time, her stepmother proved more concerned about the welfare of her own children. Albina did just a couple of years in a state school. The story goes that the head of the school wanted her to stay on but her father, my great-grandfather, would have none of it. To the very end of her life, she could recite a poem in Esperanto which she had learnt as a young child. Albina was a peasant, from a peasant family. Her grandfather was born a year after serfdom was abolished in the Austrian partition, in the very same village as Albina, yet they never met. She failed to mention this – I discovered it only recently on one of those useful websites that traces your family tree.

Albina wasn’t a moaner, but she did like to say that the first time she ever ate a full meal was when she found herself doing forced labour on a farm in the Third Reich. She must have been about seventeen. When I listened to her stories as a boy, there seemed nothing unusual about the fact that my grandmother remembered her years of enslavement under Adolf Hitler as the best time of her life. Her father was the brother of a village elder, to whom he transferred acres of land after the loss of his first wife, in exchange for a remedy to ease his mourning – vodka. Albina used to laugh as she described how he’d never believe her story that the Germans didn’t have to spend all night in the barn when a sow was about to give birth because they had so many sows, they didn’t need to worry.

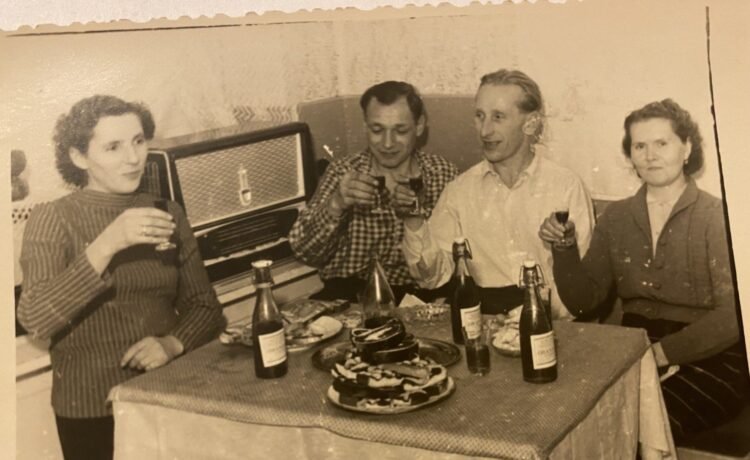

Albina (third from left) in forced labor in the village of Frankenstein. Image provided by the author.

While Albina was eating so healthily, in the home of the good Catholic Germans for whom she was doing forced labour, the state of things in her Galician village was not improving. So, once she returned home and became pregnant, she most probably started going hungry again. Hanka was born towards the end of the final year of the war. I mention it, because a Dutch-American research project published in 2008 and based on the winter of 1944-1945 when many in the Netherlands starved, has shown that inadequate nutrition during pregnancy can have a long-term effect on the genes that cause obesity. The mechanism involved is circuitous, but essentially pretty simple. The children of parents who have experienced malnutrition get a biological warning signal that goes something like this: ‘Care! This family has a tendency to run short of edibles, so best keep some supplies in store, just in case.’

But here I am talking about genes again when there might be a far simpler explanation. Albina knew about food deprivation and, when she became a mother, must have promised herself that her child would never starve. Consequently, she ensured that her daughter, Hanka, was supplied with ample quantities of food, so you wouldn’t see her ribs, so she’d grow, so her body had stockpiles of energy to draw on. And sure enough, it did.

There is just one twist to this story. Albina was thin. All skin and bones, in fact, except for a bit of muscle – my grandmother always had an imposing biceps. But essentially, she was skinny. She had her hang-ups, she was forever on the go, had no time herself to eat because she was constantly rushing to the kitchen to get second helpings for others, and never had a chance to build up any body fat. Instead, she criticized us – her grandchildren and her daughter – for being podgy. It’s all that floury food, she said. Her own stomach grew just once, three months before she died. But that wasn’t fat, it was a tumour: the same cancerous growth that had so effectively slimmed down her daughter.

When they were side by side, you’d never have known there was a family connection. Hanka was tall, broad shouldered and rotund. Albina was slight and compact; you could all too easily miss her. They never knew (they couldn’t have, given that I am discovering this only now) that, together, they represented the disjointed and tragi-comic national food history of Poland in the 20th century.

The Exchange

According to research by Alicja Budnik and Maciej Henneberg published in 2016, towards the end of the 19th century in the Kingdom of Poland, the quantity of food a peasant farmer could expect to consume over the course of a year was as follows: 135 kilograms of grain (mostly flour and bread), 18 kilograms of beans, 56 litres of milk, 3 kilograms of lard, 5 kilograms of meat and 426 kilograms of potatoes. The figures are based on medical reports dating back to the beginning of the 20th century.

By way of comparison, a well-off townie living at the same period consumed a similar quantity of grain, but was in a position to spread their bread with butter (5 kilograms per year). Urbanites drank twice as much milk and dined on seven times more meat (37 kilograms per annum; in 2019, the average Pole ate 61 kilograms). In addition, they’d have 130 eggs, which agricultural workers did not. On the other hand, town-dwellers ate half as many potatoes – most likely they were simply too full, because the evidence suggests they didn’t do much in the way of weight watching. Budnik and Henneberg’s research indicates that over 50% of gentry and burghers were overweight, as opposed to 30% of peasants. Curiously though, just 4.9% of working class men were categorized as obese, while the percentage of working class women with a weight problem almost equalled that of bourgeois women.

This was an era when paunches were all the rage. Belly bulges were flaunted by well-nourished burghers and self-assured nobles. They were patted contentedly and dressed up in elegant coats. The rich made a show of their success and the message to the world was clear: they could eat as much as they liked, there was no need for them to do anything that demanded physical strain, so all that adipose tissue could stay put. A pot-belly meant you were doing well – which is probably why modernist literature made such a point of deriding protruding, bourgeois middles. Polish readers may remember the lines from Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer from school: ‘Long live art! Forget those well-girded bellies / those paltry Philistines!’

So, there you are. To be honest, I always felt a bit uncomfortable, especially when studying Polish literature at university because, naturally, I wanted to be in the same team as those undernourished-looking bohemians. Yet my paunch identified me as a corpulent bourgeois, even if the rest of me didn’t quite fit the picture.

One way and another, the public jibes paid off and the burghers gradually got a grip on their eating habits. It was becoming patently clear that a paunch was nothing to boast about. As agricultural technology and industrial breeding took hold, food became more accessible to all. (This was less apparent in Poland and the whole Eastern Bloc, than elsewhere, chiefly for logistical reasons bound up with the erstwhile centrally planned economy. Here, pot-bellies are still sometimes viewed as status symbols. Since the transition to a market economy, however, our attitudes have been catching up.)

As the lower classes finally found themselves able to fill their stomachs and show them off to the world (in the 1960s, globally, the average calorie intake per person was 2200; by 2018 it had risen to 2800), the privileged classes began to look upon this excess of calorific intake with increased distaste.

All this sounds much like that Greek myth about a mortal who sets out on a quest for the golden fleece but, when he finds and wins it – or because he does so – gets nothing from the gods but allegations of acquisitiveness. It is one of those historical ironies that Albina did everything she could to ensure her daughter had everything she herself had lacked, and ended up looking upon what she had done with growing unease.

Today, we are witnessing a similar process worldwide. It has led to an ’epidemic’, in some cases a ‘pandemic’, of obesity: 39% of adults are overweight worldwide, and 13% fall into the obese category. A World Health Organization (WHO) report published in 2014 linked this to an unequal distribution of wealth. (‘Within the EU, 26% of obesity in men and 50% of obesity in women can be put down to inequalities in education. In groups with a low socio-economic status, the likelihood of obesity doubles.’)

A 2020 WHO report also indicated that in developing societies, obesity goes hand in hand with hunger. Those extra kilos are not, as many people suppose, a signal of prosperity, but a sign of poverty. In his book Hunger (translated into into English by Katherine Silver), Martin Caparros remarks – with all the confidence of a reporter who doesn’t hesitate to draw definitive conclusions from circumspect academic reports – that: ‘In rich countries, the poor eat a lot of cheap junk food – fat, sugar, salt – and gain monstrous amounts of weight. They do not represent the opposite of the starving: they are the other side of the same coin.’

What coin? No surprises: it’s about power. ‘Since the dawn of civilization, hunger has been one of the most powerful weapons available, an extreme form of wielding power,’ Caparros writes. Obviously, there is also coercion, violence, rape and – in richer societies – invigilation and the distribution of privileges. But the evidence suggests that, where large-scale control is involved, hunger works best. Consider the opening lines of the Internationale: ‘Debout! les damnés de la terre! / Debout! les forçats de la faim!’ (‘Arise ye workers from your slumbers / Arise ye prisoners of want…’, this ‘want’ may seem pretty vague in English, but the French ‘la faim’ is simply ‘the hunger’). As Caparros rightly observes, ‘it takes real audacity to call hunger a metaphor’, because hunger is the source of the metaphor, not the other way round.

The history of different peoples, and of humanity as a whole, can be presented in terms of a procession of personalities widely acknowledged as ‘great’ (you may laugh, but just take a look at school and university curricula.) History can be written as a chronicle of exploitation, or a sequence of chaotic social movements. It can be dressed up as a narrative about the constant transfer of information, or about tendencies to fusion and dispersal. But, in the end, it’s all about hunger. Fundamentally, it’s about food. In the final analysis, it’s the stomach that counts.

Marian

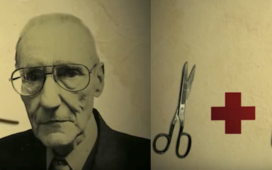

What about Albina’s husband? Was Marian, my grandfather, a peasant? Not really. He was born, reared and, to some degree, educated, in Kęty. Before the Second World War, Kęty had a population of over 7000, which made Marian an urbanite. This is not to suggest that he wasn’t undernourished. I have a photo of him, taken on the day of his First Communion, which he received courtesy of some goodly folk who sheltered him for a while in their home. The photograph reveals a considerable disproportion between his head and the rest of his body: he couldn’t find a way of growing.

Marian. Image provided by the author.

Marian was an orphan. He took his surname from his mother who simply didn’t have the time to care for him. She most probably worked as a domestic servant in the nearby town of Oświecim. In her book, The Maids who did Everything [Służące do wszystkiego], Joanna Kuciel-Frydryszak explains how children like Marian came to end up on the streets.

‘Most housemaids who had an illegitimate child were dismissed… You lost everything: your income, board and lodging, security. Furthermore, the child had a birth certificate with her father’s name given as N.N., which stigmatized her from the start.’

But all this is speculation. Who was Marian, exactly? We don’t know and, for some reason, no one in the family was too bothered about it. He was a husband, a father and the best grandfather in the world. In our household, it would not have occurred to anyone to judge any human being by their social origin. And in any case, Albina’s mother was probably an orphan too, so there was nothing of special interest to discuss.

Am I, then, a man of the people? In what percentage? How far am I descended from country folk or serfs or the workers or nobles or the merchant class? What exactly are these questions? Well, strictly speaking, they relate to a feudal cast of mind. They are questions posed by a culture in which genealogy is everything and social background means more than individual achievement. They are questions put by Michał Garapich in The Children of Kazimierz [Dzieci Kazimierza], for example. The book attempts to dismantle myths about the author’s family’s upper class origins, yet Garapich sets about his task like a purebred member of the nobility: he seeks out his ancestors and adds them to the ‘family books’.

These are questions we were taught to ask at school, so we could differentiate between Poland’s historically high-ranking families, magnates with names like Czartoryski or Zamojski, say. Doubtless, this might have made sense, once, to the Czartoryskis or the Zamojskis as they clung to their estates and sought to keep their blood pure and uncontaminated. But for Albina, Marian and Hanka drawing up a family tree of any kind would have proved impossible.

The same is true of my paunch. I may be trying to persuade you that, just below my chest, I am the proud bearer of a peasant heritage, but the truth is I’ve no idea where it came from. It could be my grandmother who was a country girl, or my grandfather who was an orphan, or indeed any of my forebearers. And not every clodhopping grandson is fat, just as not every granddaughter of peasant farmers is overweight. If I’m trying to fill the gap in my family tree it’s only because I was taught to do so at school, though I should have wisened up by now. ‘Why dwell on it?’, someone of a more practical bent of mind might ask. ‘OK, so you’ve got a middle. If it bothers you, do something about it. If not, just leave it.’

It might be more sensible to heed those specialists who offer lists of well-documented factors that cause obesity: a sedentary lifestyle (yes), driving a car (yes), work that makes no physical demands (yes), easy access to sugar and carbs (I watch those calories, I swear), a high-fat diet (yes again). And then there is age. Take a look around the streets and you’ll see that paunchiness is a common problem for men in their middle years.

It looks very much as though fatty tissue, like money, is an analogue of so many human troubles: physiological and psychological; health-related and financial; issues with our ancestors and our descendants; problems with wealth, poverty, success and failure. All this is effortlessly translated into cells that find their niche in the secret recesses of our tormented bodies. Researchers who argue that the connection between social status and excess weight is ‘complex’ and ‘not entirely understood’ may be closest to the truth. It’s very much like life – complex and not entirely understood. So if I’m still hanging on to the adage ‘follow the fat’ it is because I’m trying to fix a problem. Rather like the historians who persuade us that stories about forced drudgery under the feudal system can explain today’s world better than analysing the structure of capital markets, examining the effects of global warming, or studying epidemiology. In other words, there is a degree of arbitrariness involved, which usually meets with intense disapproval from academics, even though it is simply evidence of the fact that we are human beings with personal preoccupations, and not objective functions of historical determinants.

So why am I so hung up on my peasant genealogy? To feel better, I suppose; to (quite literally) throw off some of the weight I carry and identify, in my failings, the action of forces over which I have no control. In other words, to stop blaming myself and designate someone else as responsible.

‘I shouldn’t have to carry all the responsibility for my body by myself,’ Roxane Gay writes.

Right. So, for starters let’s try blaming Count Karol Jozef Larisch, the owner of the largest estate in the vicinity of the village where Albina was born. From now on, send your complaints to him. I bet he carried a fair bit of flab as well.

Or maybe I need a peasant paunch as my personal legacy, to connect with Hanka, Albina, Marian, and the history of the Polish working class and people as it fades in the mists of time. The fictional Caak people in Olga Hund’s novel Coots count to Three [Łyski liczą do trzech] have a third eye; in the US, skin colour can cause Blacks a lot of trouble, but it can also be a source of pride. And what do I have to offer? A nervous laugh? A tendency to scratch my back or pick at my fingernails when I’m unsure? Too many doubts? Think I’ll stick with the paunch.

Or maybe the point is to link up with other paunchy men and women, who eat their feelings because it’s the only way they have to calm their anxiety? Perhaps if we dig deep enough into the story something might eventually improve? Maybe a podgy little village boy from Silesia will feel better about himself for a moment? Or is it just that I want to explain something to myself?

Andrew

Maybe to explain that scene from Damien Chazelle’s film Whiplash in which a young jazz drummer, Andrew, attends his first rehearsal at the music conservatory he has just joined. The legendary conductor, Terence Fletcher, walks into the room. He greets Andrew with great charm and then, just to balance things, introduces a dose of terror into the equation. ‘We have an out of tune player here,’ he growls. Fletcher circles like a predator between rows of young, handsome men who look like they should be playing in Carnegie Hall, before descending on Metz, a trombonist with a chin that’s just a little too round. The wiry, muscular J.K. Simmons (who plays Fletcher) stands over Metz (played by C.J. Vana, who was later cast in a similar role in the 2017 film Fatties: Take down the House). At this point the message becomes crystal clear: there is no room for paunches in the best band in town. ‘I’ve carried your fat arse for too long, Metz!’ Fletcher roars. ‘I’m not going to have you cost us a competition because your mind’s on a fucking Happy Meal instead of on pitch!’

Blink and you’ll miss it, but Whiplash is a film about fatness. Andrew seems visibly inclined to follow in the steps of his father, a pleasant enough guy who may not have achieved much in life but is extremely fond of his son. He enjoys munching on popcorn with his boy in the cinema and doesn’t give a monkey’s about the paunch under his shirt. It makes sense then that the key moment when Andrew leaves his family to become a top percussionist is marked by his departure from the dining table. The film is not about finding a way to success, it’s about fat. Andrew’s surname is Neiman (newcomer). He’s the kid from nowhere. Before the first rehearsal Fletcher asks him if either of his parents have ever been musicians. No? Mum’s gone and Dad’s a school teacher? Too bad. Career stories and food histories tend to intertwine. After all, the provincials who migrated to the Polish capital Warsaw, hoping for a better life, were widely dubbed ‘jars’ (słoiki). Now ask yourself: what are jars for exactly? And there you are.

While I was doing my PhD and (much like any doctoral student) doubting that I’d ever get down to writing my thesis, Geoffrey Miller, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of New Mexico, tweeted: ‘Dear obese PhD applicants: if you didn’t have the willpower to stop eating carbs, you won’t have the willpower to do a dissertation #truth’.

In response, Miller’s university hurriedly barred him from admissions decisions and made him undergo sensitivity training. But I was watching and I knew. It felt true. PhDs are not for fatsos.

I had chosen to be an academic because it let me hide my shamefully tubby body behind stacks of books

‘There was something consoling about being in higher education and living a life of the mind. My body meant nothing,’ Roxane Gay writes.

But, as Miller said, the intellectual life is not for the obese. From late 19th century decadent fat-shaming through to the present, intelligence and talent have been consistently associated with a slim, ascetic-looking body. Consider Terence Fletcher’s physique in Whiplash, or the build of Steve Jobs (no wonder Steve Wozniak had to go).

‘People don’t expect a writer making a speech at their event to look like me,’ Roxane Gay writes.

Towards the end of the 20th century, tums – convex and concave – swapped roles. Their significance changed, but there was an asymmetry about the process. A protruding belly used to signal that you belonged to the upper echelons of society; today it prevents you from climbing the career ladder. The contemporary paunch is not the urban paunch of the late 19th century. It no longer indicates stability and self-confidence. On the contrary, it is interpreted as evidence of indolence, lethargy and lack of self-discipline.

It is the stomach of thoughtless consumers; the belly of that malicious figure, Eric Cartman, in the animated sitcom South Park; the spare tyre of an importunate, greedy rabble. Get it? Today, the paunch is associated with thugs. And nobody wants a thug at their nice, posh soirée.

Following Miller’s #truth tweet, a team led by Jacob M. Burmeister, a doctoral student at Green State University, released some research indicating that obesity lowers your chances of being accepted for a PhD in psychology, even if your references include a greater than average number of flattering adjectives. Burmeister’s explanation may be different from Miller’s, but essentially it points to a similar connection: the bigger the paunch, the smaller the likelihood of getting that doctorate.

I can’t explain why but, somehow, I slipped through the net. I defended my thesis and managed to find a decent job. But, in the small world I inhabit, you don’t see many paunches. It’s like in films: plenty of thin, pipe-smoking male actors and even thinner female actors who also smoke pipes (though increasingly less). Sometimes, I might sneak a peek to see if there isn’t a slight protuberance hiding under somebody’s shirt, or some kind of rotund body curve revealed in profile. If I find one, initially I find it hard to believe what I’m seeing, and then for a moment I experience a sense of relief that I am not alone.

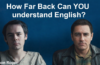

Albina first from left, Marian second from right, year unknown. Image provided by the author.

Maciek

Fatso, hog, donut, whale, barrel, piggy, chubby cheeks, suet, ‘maciek’… In Poland, the last of these is a first name: the diminutive of Maciej. But the word also means pot-belly. To this day I find it hard to understand what drove Hanka to imagine that if she called her younger son (me) Maciek, the elder would be spared the nickname in the playground. She was, after all, an intelligent and sensible woman, if somewhat embittered. That’s why I prefer to be known as Maciej not Maciek, as if the difference between a slim ‘j’ and a sprawling ‘k’ were some kind of magic charm.

For years I managed to kid myself that the guy with the bulging middle was not the real me; that under all that adipose tissue lay a hidden, more authentic ‘I’ waiting to be revealed to the world once a few excess kilos had been shed. But how long can I delude myself? How long am I meant to wait for real life to begin?

So, here goes: yes, I, Maciek, am in possession of a paunch.

On occasion, it can even be quite useful. It has been known to serve as a practical aid in holding up boxes or carrying little people. Sometimes I tap rhythms on it, as if it were a drum and then I forget, for a minute or two, what a shy pot-belly it is. And when I hear from friends and colleagues how depressed they feel, I think to myself that, in this matter at least, my tum has never failed me. When it’s nice and full, I feel genuinely happy.

One day, I may yet lose weight. I’ve managed it before once or twice: after splitting up with girlfriends (because I was unhappy but also to stay on the meat market, as I searched for another partner). Or while I was writing a book and dreaming that, when it was published, I’d look lean and fit at ‘meet the author’ gatherings. Or, just once, when I was abroad for a few months doing two jobs at once to earn enough for my university course.

When I think about it, I see that my paunch allowed itself to be contained only when I very much wanted to be a better version of myself. Which suggests that I didn’t much like the person I was. The energy that motivates social mobility emerges from a similar aversion to one’s position in the social group. You need to harbour a real dislike for your status in life to want to tear yourself away, no matter the cost.

More often than not, however, I hate my paunch and wish it wasn’t there, and of course, this is a harmful attitude, because if I cannot tolerate my own belly then I must feel the same about pot-bellies belonging to other people, and about their bad eating habits (once believed to be healthy) inherited from oppressed ancestors who spent their lives going hungry, and as their history is also my history, am I, when I feel disgusted by my paunch, betraying those who did so much to help me achieve more in life than they were able to, what’s more, there is a debatable premise here that their lives were ‘worse’ than mine, though of course this wasn’t how they saw it at the time because they simply wanted to ensure I didn’t have to worry about filling my stomach, so I could once and for all stop thinking about it, but when I want to rid myself of that paunch, am I looking to rid myself of them, or am I, in fact, doing the exact opposite?

I can easily imagine who I might have been if, historically, things had been different. If there had been no Polish People’s Republic and no World War II; if, in 1913, Celia Steele from Sussex County, Delaware, had not invented chicken factory farming; if starving peasants had stayed hungry and paunchy nobles had stayed in charge; if, in other words, the worst-case scenario had actually come about. This is what Albina’s genes warned her against. I am thinking of an undernourished boy who does well at school but has to go back to grazing cattle in a nearby field once he has done two years of education, and then becomes an embittered man who knows that imagining a better life causes intense pain so he seldom allows himself to do it. That boy lives somewhere in me. He is all skin and bones, and we don’t have very much in common, but it’s impossible for me not to like him. I am doing my best to help him get used to the world in which we both live. Patiently, I reassure him that there is enough food for tomorrow and the day after, and for years to come. He seems to be coming round to the idea but it’s a slow process and, at times, he still insists on having things his way.