(RNS) — Imagine a job interview where, to get the gig, your spouse must answer intrusive questions about their fertility, personal religious beliefs and their own career trajectory.

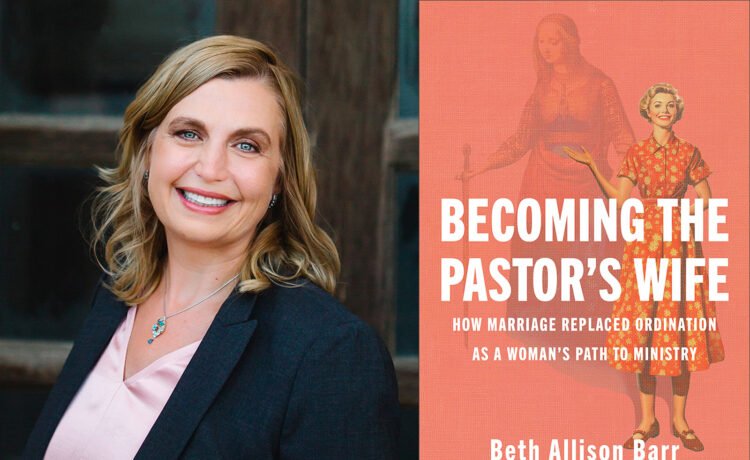

Such interrogations are common for many pastors’ wives across white evangelicalism, according to medieval historian Beth Allison Barr — herself a pastor’s wife and the James Vardaman Endowed Chair of History at Baylor University. In her new book, “Becoming the Pastor’s Wife: How Marriage Replaced Ordination as a Woman’s Path to Ministry,” that’s only the start of the often-unspoken expectations awaiting many women who pair up with pastors. Their appearance, homemaking and parenting are often under scrutiny, and their unpaid labor is considered a given.

Barr isn’t arguing for an end to the role itself, but she wants everyone to know that the job’s expectations are based in culture more than Scripture. Though the only avenue in some denominations for women to pursue a calling to ministry, “pastor’s wife” is not the result of a biblical mandate, Barr argues, but of history.

RNS spoke to Barr, author of the 2021 bestseller “The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth,” about her own experience as a pastor’s wife, the medieval Christian women who pastored both women and men, and her thoughts on how white evangelical Christians might reframe their view on pastors’ wives. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What kind of expectations did you find are placed on pastors’ wives?

Probably the hardest expectation that’s often placed on women in these roles is to be a mom. This has absolutely nothing to do with whether a man is doing a good job as a pastor, yet it’s an expectation that a minister’s family should have children who are well-behaved. For women who experience infertility — and I was one of those women — what does it do when the pastor’s wife can’t be a mom? I remember being confronted head-on by people in more than one congregation about my inability to produce a child. I think it really highlights the weirdness of this role, this unofficial position that is connected to another person’s job.

What does the Bible say about the role of a pastor’s wife?

There is no clear example to point to. And so, here we have this role that has no clear biblical grounding. Almost all of the female leaders in the Bible, we know very little, perhaps nothing, about their marital status. We’ve taken this role that is nowhere in the Bible and then have held it up as sort of the ideal model for biblical women, for godly women.

What historical factors led to the role of the pastor’s wife being what it is today?

In the early Christian world, there was a lot of emphasis placed on unmarried people serving or people giving up their spouses. The Reformation changes this. For early Protestants, the way you distinguished a Protestant minister was that he was married. In many ways, the minister’s wife becomes a symbol of resistance. She literally embodies this conversion experience. These women broke the law to get married, and marriage becomes part of the job description to be a minister.

For a good while, though, we still see women who are serving in independent ministry roles, or women who are married to pastors who are rejecting the pastor’s wife image. There were multiple options for women, and it’s not really until the latter part of the 20th century that we begin to see this idea that the best way to be in ministry as a woman is to be married to a pastor.

How is the decline of women’s ordination related to the rise of the pastor’s wife in the evangelical church?

I write about some powerful women who were serving as pastors to men in the Southern Baptist Convention well into the post-World War II era. This is where the shift happens. In the aftermath of World War II, there was an effort to get men back into jobs, to get them into college, in part by discouraging women from being in jobs that were seen as in competition with men.

In the 1960s and ’70s, we see more women in seminary wanting to be pastors. It is also at this moment that we begin to hear, in more conservative spaces, voices saying it is unbiblical for a woman to be a pastor. They begin fighting against women’s ordination while elevating the pastor’s wife role. Women can still be in ministry, but you have to do it “God’s way.”

The pastor’s wife role begins to be weaponized against female pastors, and to be made extremely visible. Especially in the ’90s, you see seminaries creating institutes to train up pastors’ wives. This is also when you see the spike in this genre that is geared towards helping women become pastors’ wives.

Your book’s cover underscores some of the book’s messages.

Women have throughout church history served in independent leadership roles that were recognized and ordained by men — until now. Members of the Southern Baptist church are pushing to pass this amendment that says women cannot serve in any designated pastoral position, which is one of the most restrictive limits placed on women in Western church history.

I wanted to show in this book cover the scope of history, as well as the narrowing of a woman’s ministry role. We have this image representing this woman who’s this 1950s and ’60s “Leave It to Beaver” minister’s wife. And behind her is an early medieval saint, Catherine of Alexandria, who became the patron saint of preachers. We have this woman who encapsulates the leadership roles that women held, and now we have this reduction.

Do we have any alternatives to the white evangelical pastor’s wife?

I found some stark differences in books written by Black pastors’ wives that gave me hope. They don’t argue that it’s a biblical role. They say it comes from history, stemming from enslaved communities where the stable characters were women who were spiritual leaders and church mothers. I’m thinking specifically about a 1976 book written by Weptanomah Carter. Especially in these Black pastors’ wives books before 2005, we see that many are co-pastors with preaching and pastoral care authority. I saw more focus on women’s independent gifting and the ability of women to serve in ministry roles that were outside of even their own churches. It showed me how historically constructed these roles are, which means that you can do it differently.