(The Conversation) — In the Old Town of Rhodes, a picturesque tourist destination in the Aegean Sea, stands a monument to a dark period in the island’s past. In the former “Djuderia,” the Jewish quarter, a marble obelisk commemorates the deportation of the island’s small but vibrant Sephardic Jewish community to Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 23, 1944.Jewi

The 1,700 Jews of Rhodes had the misfortune not only of experiencing deportation late in the war, when Allied victory was almost in sight, but also of enduring the longest journey of any Jewish community sent to Auschwitz — a treacherous voyage that lasted 24 days.

In July 2024, 80 years after the tragic deportation, scholars, government officials, community leaders and Jews from Rhodes and their descendants — known as Rhodeslís — gathered on the island, which has been part of Greece since 1947, for a week of commemorations. I participated as a historian from Seattle – home to a large Rhodeslí community – and as chair of the University of Washington’s Sephardic Studies Program.

The contemporary monument to victims from the island of Rhodes.

Yywilk/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The fate of the Jews on this remote island is testament to the scale and reach of the Holocaust: how the genocide of Jews remained a Nazi priority to the end, and the range of Jewish cultures decimated during the war. The Holocaust destroyed not only Yiddish culture of Eastern Europe, but also Ladino culture of the eastern Mediterranean.

Ottoman echoes

Like many Jewish communities in the eastern Mediterranean, the Jews of Rhodes are Sephardic Jews, whose forebears were expelled from Spain in 1492 and settled in the Ottoman Empire.

While a Jewish presence on Rhodes dates to antiquity, around the second century B.C.E., the main Sephardic population emerged after the Ottomans conquered the island in 1522. Under the Ottoman Empire’s Sunni Muslim rulers, Jews on Rhodes paid special taxes in exchange for maintaining their own institutions, rabbinic traditions and Sephardic language, known as Ladino or Judeo-Spanish.

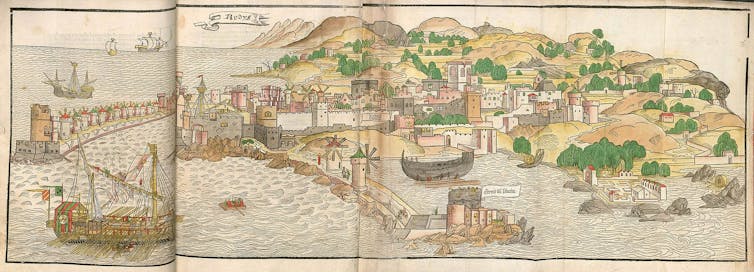

A 15th century woodcut depicting Rhodes, by Bernhard von Breydenbach.

Erhard Reuwich/Wikimedia Commons

In 1840, an economic dispute about the trade in natural sea sponges tested relationships among the island’s communities. With the support of European consuls, Greek Orthodox Christians on the island incited violence by promulgating a blood libel: the antisemitic accusation that Jews use the blood of Christian children for ritual purposes. But the Ottoman sultan intervened, affirmed the blood libel was false and restored calm.

In 1912, the Italians conquered the Dodecanese Islands, of which Rhodes is the largest. Still, Jews maintained cordial relations with their Muslim neighbors. Auschwitz survivor Samuel Modiano recalled that his father spoke Turkish with his Muslim neighbors, whereas relations with local Christians remained “decidedly thornier.”

These dynamics help explain why a Torah scroll featured in the Djuderia’s renovated Jewish museum survived the Nazi occupation due to the intervention of the local Mufti, a Muslim religious leader, who hid the Torah in a local mosque.

Italian paradoxes

Life transformed radically for the island’s 4,300 Jews under Italian control, which lasted from 1912 to 1943. Italy saw Ladino as a Romance language, like Italian, and therefore considered the Jews natural partners in spreading “Italianness” in the region. In 1928, once Benito Mussolini had risen to power, the fascist government established a prominent rabbinical seminary on Rhodes, to which students flocked from across the Mediterranean.

But if Italian fascism appeared to contribute to the flourishing of the island’s Jews, it also contributed to their downfall.

In 1938, Mussolini followed Adolf Hitler’s lead by introducing his own antisemitic Racial Laws. The laws defined Jews as a separate, inferior race; banned intermarriage; and excluded Jews from military, government and professional positions, as well as public schools.

Modiano, who played a central role in the recent commemorations, recalled the humiliation of being expelled from school: “That day I lost my innocence. In the morning I woke up as a boy. At night I went to sleep as a Jew.”

As part of a broader Italianization campaign, the laws also expelled Jews who had arrived on Rhodes after 1919. Many Jews on the island had previously held Ottoman nationality, and Turkey was just 10 miles away. But as part of its own nationalization project, the Turkish republic denied them permission to repatriate.

In letters to relatives in Seattle, Clara Barkey, whose father was originally from Aydin, Turkey, likened her family’s expulsion in 1938 to the exile of her forebears from Spain in 1492. Barkey ultimately secured passage to Tangier, Morocco, one of the few places willing to accept Jews, given immigration quotas in places like the United States.

Others joined Rhodeslí diaspora communities in places like Argentina, Belgium and what are now the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zimbabwe.

Destruction

For the 1,000 Jews forced to leave Rhodes in the late 1930s, the expulsion was a blessing in disguise. The Jews who remained could not fathom the fate that would befall them.

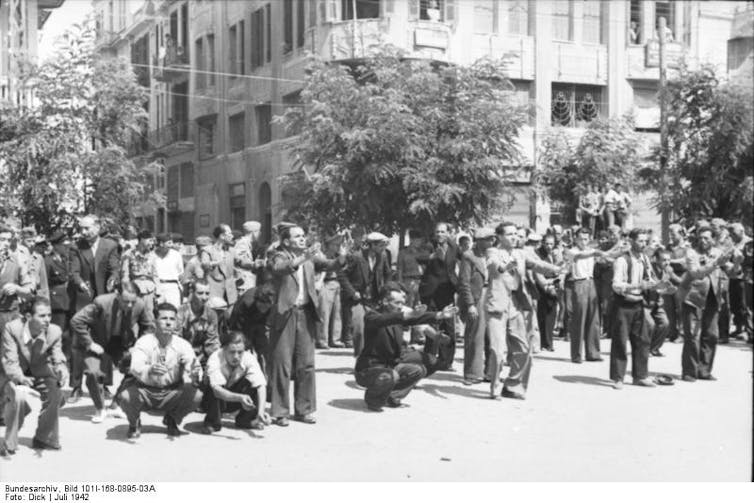

Jewish residents are humiliated in a public square during a roundup in Salonica, Greece, in 1942.

German Federal Archives via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

In September 1943, after Italy surrendered to the Allies, German forces invaded the island. But for 10 months, the Nazis did not implement new anti-Jewish measures. On Rhodes, Jews did not face ghettoization, nor were they forced to wear the yellow star. By the following summer, the tide of the war was turning in the Allies’ favor.

Nevertheless, the Third Reich made plans to extend the “Final Solution” to the Dodecanese. On July 20, 1944, SS officers corralled most of the island’s Jews into a makeshift concentration camp. The pretense was an identity document check, a trick that sealed their fate. Yet the local Turkish consul, Selahattin Ülkümen, managed to exempt more than 40 Jews who were, or whom he claimed to be, citizens of neutral Turkey.

The SS packed the island’s Jews into cargo holds of three ships used to transport livestock. En route to mainland Greece, the ships stopped to collect 85 Jews from the island of Kos and continued to the port of Athens. With little food and water, several prisoners died during the week at sea, and their bodies were thrown overboard.

In Athens, the Rhodeslís followed the rail path previously trodden by Greece’s 60,000 Jews – including the country’s largest Sephardic Jewish community, in Salonica. As the transport from Rhodes neared Auschwitz, the U.S. bombed nearby chemical plants and refineries – but never the railroads, gas chambers or crematoria. Only 150 Rhodeslís survived Auschwitz.

Samuel Modiano, one of the few survivors.

Fcarbonara/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

The Third Reich’s decision to liquidate the Jews of Rhodes so late in the war underscores the extent of Hitler’s fixation on the mechanized mass murder of Jews, despite the cost to the war effort. Nazis allocated their dwindling resources to deport small Jewish communities on the fringes of Europe, even as the British bombarded Rhodes, and even as the Nazi occupation would collapse within six weeks. As survivor Stella Levi uncannily recalled, “It would have been simpler to murder us all here.”

The 2024 commemoration events on Rhodes paid homage to the victims of the Holocaust – no Jews with prewar roots on the island remain there today. But they also honored the community’s traditions, cuisine and spirit, kept alive among Rhodeslís in diaspora who made the pilgrimage to their ancestral island – an “island of memory.”

(Devin Naar, Assciate Professor of History and Jewish Studies and Chair of the Sephardic Studies Program, University of Washington. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()