(RNS) — In May 2023, Kerlin Richter, then a priest at an Episcopal Church in Portland, Oregon, attended an adoption ceremony that legally recognized her baby’s three parents. The event, featuring a large, celebratory danish pastry and a Mary Oliver poem, was a step toward formalizing Richter’s family, which includes her husband with whom she has an adult child, and her partner, with whom she had a baby in February 2023.

Soon after, eager for advice on how to disclose the shape of her family to her congregation, Richter, 46, spoke to her bishop. But in June, her bishop gave her a choice: return to monogamy or renounce her ordination vows.

“This is just the shape of my family,” said Richter, who, after experiencing a yearlong church investigation she called “abusive,” ultimately renounced her ordination in June. “We have a really sweet baby who has a mama, a daddy, a papa, a couple of great siblings. And I don’t see how any of that should prevent me from being priest.” Richter’s bishop declined to comment for this story.

As polyamory gains visibility in the broader culture, it remains enough of a taboo in most Christian denominations that they lack explicit policies. In the most progressive of these denominations, people in or exploring these relationships, which involve emotionally intimate, often sexual, relationships with more than one person, are weighing in.

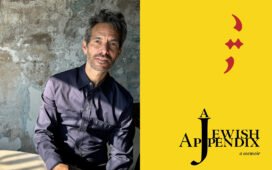

Kerlin Richter. (Courtesy photo)

Earlier this year, an Episcopal Church task force submitted two resolutions intended to generate discussion of “diverse family and household structures” in the church. Neither resolution — one would have prompted a study of the topic, and the other would have offered limited disciplinary protection for clergy and laity who disclose alternate family structures — advanced at the church’s annual meeting in June. In addition to Richter, at least two other non-monogamous Episcopal priests have renounced their ordination vows due to tensions between their church roles and family structures.

In 2023, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada’s Court of Appeal declined to suspend a minister in a polyamorous relationship because its bylaws don’t explicitly prohibit it. Months later, ELCIC delegates voted to create national resources to support conversations that include “ethical non-monogamous relationships.”

Conversations about polyamory have begun, too, in Unitarian Universalism, a faith group that has Christian roots but rejects dogma and includes people of all beliefs. The denomination-sponsored sexuality education program includes a workshop for parents about polyamory. That curriculum has also been used by members of the United Church of Christ, whose Open and Affirming Coalition is hosting a workshop on polyamory at its national gathering in late September of this year.

“Non-monogamy is probably more present in your life than you think it is,” said the Rev. Tori Mullin, a national staff person for the United Church of Canada who spoke to RNS in their personal capacity. Non-monogamy, Mullin pointed out, can include an aging person seeking a companion while caring for a spouse with memory loss or a young person dating multiple people at once.

Such relationships aren’t unbiblical, Mullin said, as the Bible doesn’t offer one cohesive model for Christian families. The Hebrew Scriptures often depict non-monogamy as a social safety net, and Jesus emphasized “ethical relationship in community and care for the marginalized,” said Mullin.

Some polyamorous Christians also say it’s important to counter the church’s attachment to monogamy as the only vehicle for holiness. “I don’t want a biblical marriage,” said Jennifer Martin, a polyamorous member of United Church of Christ, who said she no longer finds patriarchal models in Scripture helpful. “I want to have a marriage where I have Christ-like values … I don’t think that consensual, meaningful, thoughtful sex is a sin in any context.”

Others point to the Bible’s examples of polygamy as tantamount to polyamory, or even the Trinity as a theological instance of polyamory.

Jennifer Martin with her husband, Daniel, right, and her partner, Ty. (Photo courtesy Jennifer Martin)

Still, for most Christians across the theological spectrum, polyamory isn’t compatible with their beliefs. David Bennett, a onetime gay atheist activist and now celibate gay Christian in the Church of England, is also a theologian at Oxford University researching gender, sexuality and desire. While he understands craving universal love, he attributes interest in polyamory in part to a resistance to live according to God’s will.

“The idea that we need sex to be whole is a fundamental problem, (as is the idea) that my desire must win, or I am harming myself,” said Bennett, who thinks Christians are called, instead, “to deny myself, carry my cross and follow Jesus. Not my will, but your will be done.”

For many, even progressive Christians, theological justifications for polyamory amount to overreach. Aaron Brian Davis, an LGBTQ+-affirming Episcopalian and Ph.D. candidate at the University of St. Andrews’ School of Divinity, is skeptical that there’s a strong case to be made for the practice. Davis sees two scriptural models informing how Christians might unite their desires to God — celibacy and marriage — which Davis believes is available to people of all genders and sexual orientations.

Mullin, who came out as polyamorous in 2022, rejects the suggestion that polyamory is selfish or simply about having more sex. “When my needs are not met, I cannot be the best partner and parent I can be. I cannot be the best pastor,” they said. “I’m looking to connect with people who challenge me, who care for me, who bring joy and vibrancy into my life.”

Tori Mullin. (Courtesy photo)

One of those people is Mullin’s spouse; the two celebrated their 10th wedding anniversary in 2022, and as Mullin embraced polyamory that year, they reaffirmed their wedding vows in a simple front-lawn ceremony.

“We got married at 22. We’re totally different people. We want to be together for the rest of our lives. We also know that our identities have changed, our needs have changed. So how do we come together in this moment and say, this is what I’m committing to,” Mullin said about the event.

Polyamorous Christians emphasize that clear communication and boundaries are key for successful non-monogamous relationships. That intentionality, they argue, can result in healthier relationships than are found in many traditional marriages. Martin, who lives with her husband, two children and partner in Richmond, Virginia, said she and her husband approached the topic of polyamory “thoughtfully” in 2015.

“We really valued each other’s autonomy and had a lot of trust in each other that we were going to be focused on each other and put the family first,” said Martin. “We read books, we went to a couple’s counseling and we joined a family-friendly Virginia polyamory group.”

Like Mullin, Martin, 36, was raised in a more conservative Christian context and married in her early 20s. In 2018, Martin met her partner, Ty, who increasingly became a part of the family until moving in during March 2020. Though Daniel and Ty are both in a relationship with Martin, they don’t date each other.

“It wasn’t just something I did because it was trendy,” said Martin. “This is a real devoted, dedicated relationship, and I take both very seriously. I consider myself married to two people.”

Martin, who observes a “struggle for people who are non-monogamous having basic legal rights in America,” says being openly polyamorous has been a non-issue in her United Church of Christ congregation — just weeks ago, Ty became an official member of the church.

Others have made changes to pursue polyamory. After a church leader confronted him about being polyamorous, the Rev. Bryan Demeritte, 52, left his Florida United Church of Christ congregation in 2008. These days, he is a seminary professor and part-time pastor of a Unitarian Universalist congregation in Minnesota, and he’s open about his two partners, his legal husband, Deron, whom he met on a dating site in 2006, and Joshua Rodriguez, whom he has known since 2019 and wishes he could legally marry.

Bryan Demeritte, a Unitarian Universalist pastor and farmer, center, with his husband, Deron Demeritte, left, and Joshua Rodriguez, right. (Photo courtesy Bryan Demeritte)

The trio moved from Florida to rural Minnesota in late 2021 and live on their 10-acre regenerative farmstead (with four vineyards, two guard geese and 77 chickens). He plans to launch a social media channel featuring his family and their farming practices.

“There are lots of people doing that,” said Demeritte of the proposed farming platform. “But I can almost guarantee you that there’s not an out, gay, polyamorous family with people of color, one of whom is an immigrant and one who is a first generation American.”

Though he spends most of his time working on the farm, which his family has dubbed “Loving More Farmstead,” he also hopes to write a book called “The More Love the Better,” presenting theological frameworks for non-monogamy.

“If churches say things like, ‘open hearts, open minds, open doors,’ or ‘we welcome everyone,’ and ‘we’re radically hospitable,’ … there’s always, it seems, some sort of limit on that,” said Demeritte. “And what I would hope people of faith can understand, is that love is love is love.”