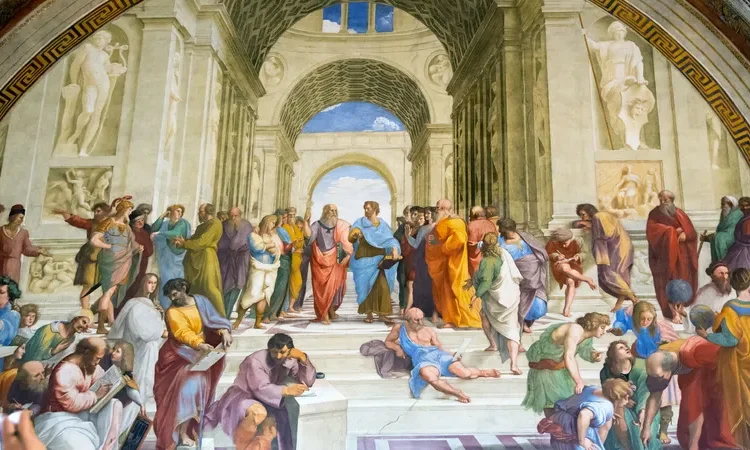

Among the wonders to behold at the Vatican Museums are the larger-than-life forms of the titans of Greek philosophy. It’s widely known that at the center of Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens, which dominates one wall of the twelve Stanze di Raffaello in the Apostolic Palace, stand Plato and Aristotle. In reality, of course, the two were not contemporaries: more than three decades separated the former’s death from the latter’s birth. But in Raphael’s artistic vision, great men (and possibly a great woman) of all generations come together under the banner of learning, from Anaximander to Averroes, Epicurus to Euclid, and Parmenides to Pythagoras.

Even in this company, the figure sitting at the bottom of the steps catches one’s eye. There are several reasons for this, and gallerist-YouTuber James Payne lays them out in his new Great Art Explained video on The School of Athens above.

It appears to represent Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher associated with ideas like change and the unity of opposites, and a natural candidate for inclusion in what amounts to a trans-temporal class portrait of philosophy. But Raphael seems to have added him later, after that section of the picture was already complete. An astute viewer may also notice Heraclitus’ having been rendered in a slightly different, more muscular style than that of the other philosophers in the frame — a style more like the one on display over in the Sistine Chapel.

In fact, Michelangelo was at work on his Sistine Chapel frescoes at the very same time Raphael was painting The School of Athens. It’s entirely possible, as Payne tells it, for Raphael to have stolen a glimpse of Michelangelo’s stunning work, then gone back and added Michelangelo-as-Heraclitus to his own composition in tribute. There was precedent for this choice: Raphael had already modeled Socrates after Leonardo da Vinci (who was, incredibly, also alive and active at the time), and even rendered the ancient painter Apelles as a self-portrait. With The School of Athens, Payne says, Raphael was “positioning ancient philosophers as precursors to Christian truth,” in line with the thinking of the Renaissance. In subtler ways, he was also emphasizing how the genius of the past lives on — or is, rather, reborn — in the present.

Related content:

Take a 3D Virtual Tour of the Sistine Chapel & Explore Michelangelo’s Masterpieces Up Close

Ancient Philosophy: Free Online Course from the University of Pennsylvania

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.