This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 783 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, karōshi prevention.

Yves here. I imagine readers will take issue with this post, analytically and practically. Let’s start out with the lack of authority economists have to discuss climate change analyses, given their acceptance of the destructive work of William Nordhaus, appallingly legitimated by giving him a Nobel Prize. The authors are on extremely thin ice in criticizing the caliber of degrowth studies in light of how they’ve celebrated appalling poor studies that fit their preferences. Steve Keen is good one-stop shopping for an evisceration of his claims.

This article pointedly ignores the lack of any solutions to our accelerating climate change crisis that are remotely adequate to the scale of the problem. It also takes the position that the needs of the economy take precedence over the future of the biosphere and the intermediate -term survival of something dimly representing modern civilization (we are likely past that being an achievable outcome, but it should at least be acknowledged as an aim). And it also implicitly ignores that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

By Ivan Savin and Jeroen van den Bergh. Originally published at VoxEU

In the last decade, many publications have appeared on degrowth as a strategy to confront environmental and social problems. This column reviews their content, data, and methods. The authors conclude that a large majority of the studies are opinions rather than analysis, few studies use quantitative or qualitative data, and even fewer use formal modelling; the first and second type tend to include small samples or focus on non-representative cases; most studies offer ad hoc and subjective policy advice, lacking policy evaluation and integration with insights from the literature on environmental/climate policies; and of the few studies on public support, a majority and the most solid ones conclude that degrowth strategies and policies are socially and politically infeasible.

In the last decade, numerous studies have been published in scientific journals that propose the strategy of ‘degrowth’, as an alternative to green growth (Tréquer et al. 2012, Tol and Lyons 2012, Aghion 2023). The notion of degrowth refers to reducing the size of the economy to confront environmental and social problems. While having little academic stance (yet), the topic is receiving quite some attention in the media and the public sphere in general. Witness two conferences organised in the European Parliament.

To assess the scientific quality of degrowth thinking, we conducted a systematic literature review of 561 published studies using the term in their title (Savin and van den Bergh 2024). This allowed us to determine the share of studies offering conceptual discussion and subjective opinions versus data analysis or quantitative modelling. In addition, we examined if studies addressed climate/environmental policy, including policy support/feasibility, and whether this was well embedded in the broader literature on this.

Distribution of Studies Over Time, Countries, and Presence of Scientific Methods

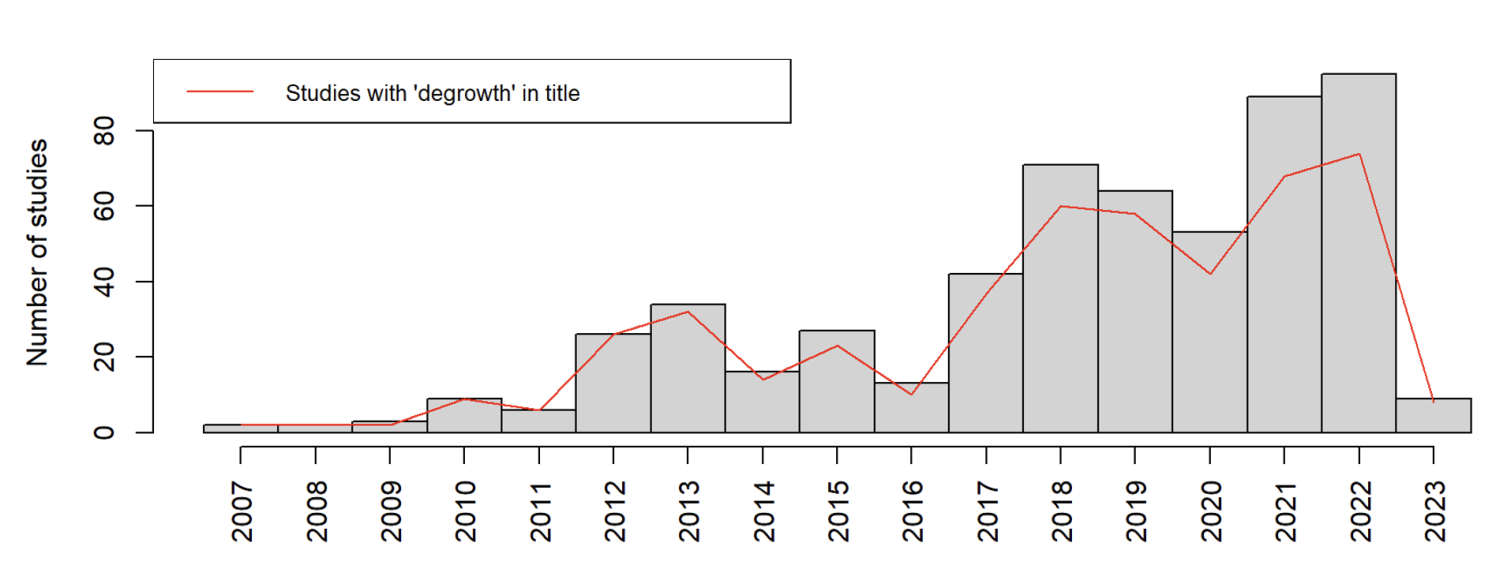

Figure 1 shows a growing number of studies on degrowth over time. As indicated by the red line, ten years ago virtually all studies in this vein explicitly mentioned the term “degrowth” in their title, while more recently many use the vaguer term “postgrowth” instead, possibly to reduce resistance.

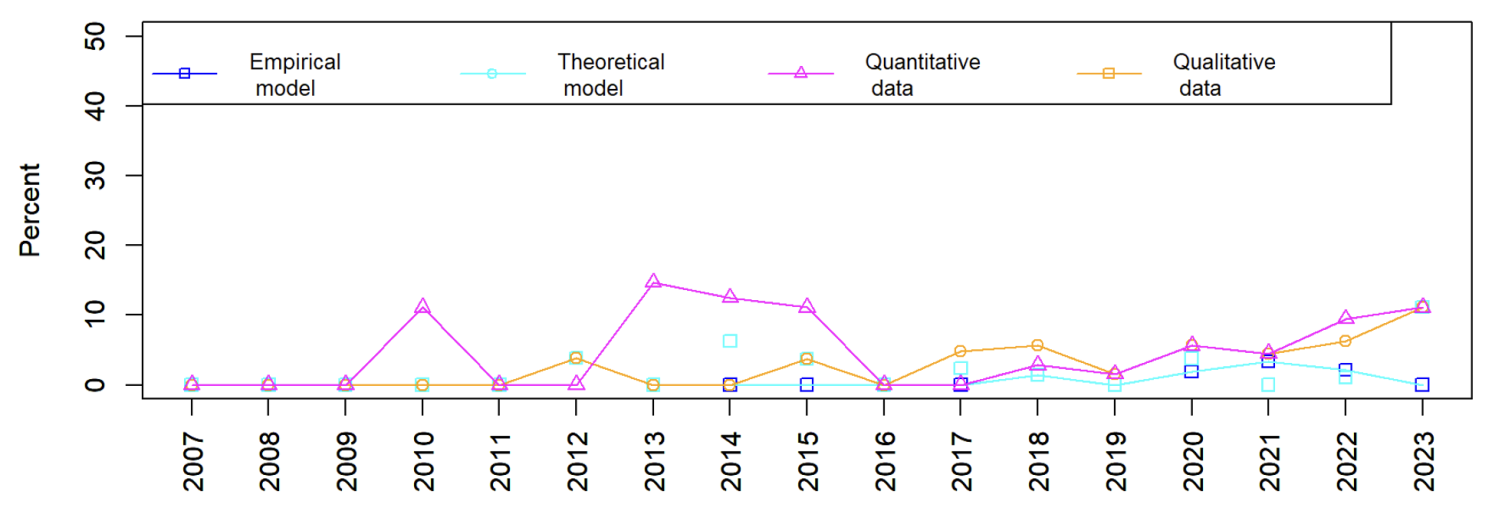

The large majority (almost 90%) of studies are opinions rather than analysis. Only nine studies (1.6% of the sample) use a theoretical model, eight (1.4%) employed an empirical model, 31 (5.5%) performed quantitative data analysis, and another 23 studies (4.1%) qualitative data analysis (e.g. interviews). As Figure 3 shows, there is no clear trend indicating that the share of studies with a concrete method is increasing.

Figure 1 Time distribution of academic publications on degrowth

Note: The histogram depicts the frequency of studies by year while the red line indicates the number of studies that used “degrowth” (as opposed to post-growth) in their title.

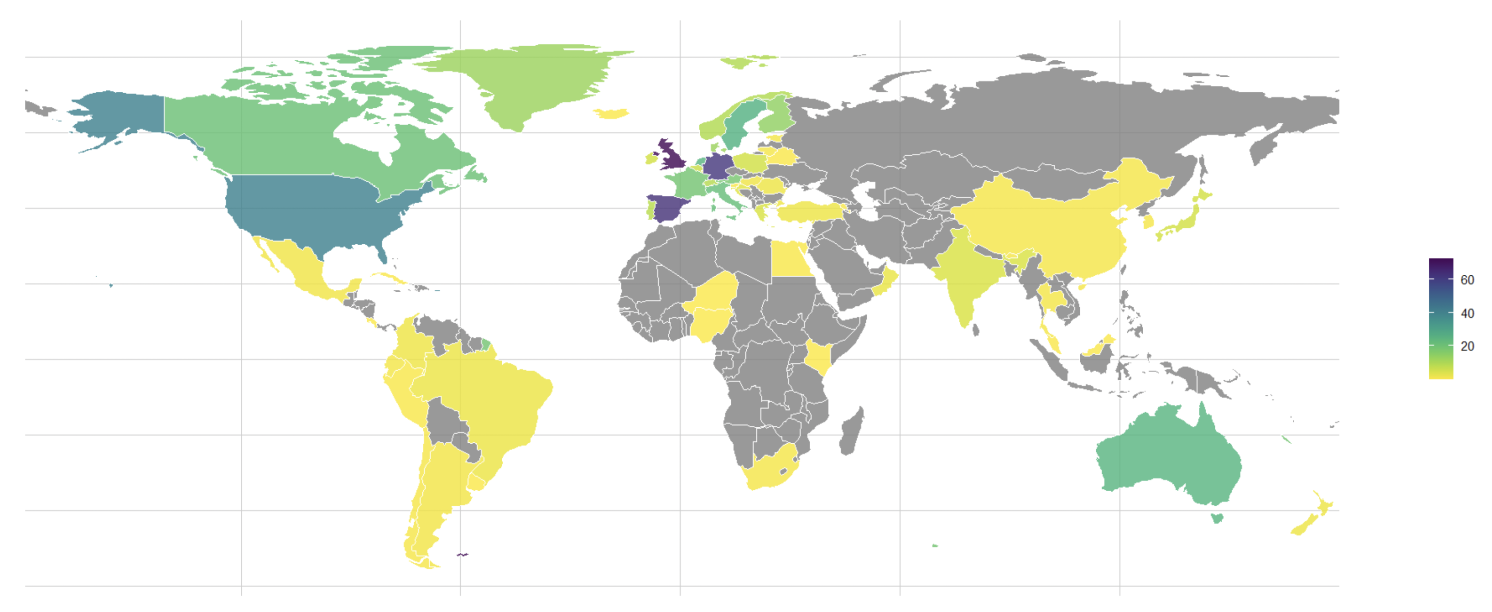

Most authors in the sample are affiliated with institutes in Western Europe and the US (Figure 2), with the UK, Spain, and Germany leading by a large margin. This is in line with earlier research finding that there is little support for degrowth in the Global South (King et al. 2023).

Figure 2 Geographical frequency of author affiliations

Figure 3 The time pattern of the share of studies using one of the four methods

Focus on Small Samples and Lack of Systemic Perspective on the Economy

Inspecting the 54 studies that used qualitative or quantitative data analysis, we find that they tend to include small samples or focus on peculiar cases – for example, ten interviews with 11 respondents on the topic of local growth discourses in the small town of Alingsås, Sweden (Buhr et al. 2018), or two locations of ‘rural-urban (rurban) squatting’ in the Barcelona hills of Collserola (Cattaneo and Gavaldà 2010). This easily gives rise to non-representative or even biased insights. This weakness of empirical research on degrowth is understandable to some extent. The idea of degrowth is so far from reality and has seen no serious implementation, which makes good empirical studies a challenging task. Past experiences as in communist countries (e.g. Cuba), low-growth countries (e.g. Japan), or economic decline due to COVID-19 do not serve as convincing examples of degrowth. Arguably the best one can achieve is stated-preference research and behavioural experiments. Whereas this should then be done for sufficiently large samples, this ambition tends to be lacking in studies on degrowth. The few studies that do use larger data sets tend to not collect these themselves but rely on data of a general nature, such as the European Value Study (Paulson and Büchs 2022). The problem is that these do not explicitly inquire about degrowth but pose rather general questions about growth versus environment which are open to interpretation (Drews et al. 2018). As a result, the associated studies arrive at overly optimistic conclusions about support for degrowth (Paulson and Büchs 2022). This is confirmed by several solid studies by psychologists which find that most participants in experiments tend to emotionally react negatively to a message of advocating radical degrowth, while many perceive degrowth strategies as a threat. In addition, earlier surveys which try to clearly separate the distinct positions on growth versus environment (like by Drews et al. 2019) find more support for ‘agrowth’, i.e. being agnostic about or ignoring GDP (van den Bergh, 2011), than degrowth among academic researchers broadly as well as the general public.

Since degrowth strategies tend to be radical, i.e. they propose major changes in socioeconomic systems, it is crucial to have good insight into their systemic and macroeconomic consequences. But unfortunately, many studies propose to undertake a large socioeconomic experiment with big socioeconomic risks without having insight into the bigger picture. Most quantitative and qualitative studies focus on small and local issues, usually with non-representative and very small samples – making it impossible to draw conclusions about the systemic impacts. Out of the 561 studies we reviewed, only 17 studies using theoretical or empirical modelling shed some light on these broader consequences. Several of them draw rather pessimistic conclusions in this regard. For example, Hardt et al. (2020) find that a shift towards labour-intensive service sectors – part of many degrowth proposals – would result in small reductions in overall energy use because of their indirect energy use. And Malmaeus et al. (2020) conclude that universal basic income, a popular theme in degrowth writings, is less compatible with a local, labour-intensive and self-sufficient economy than with a global, capital-intensive and high-tech economy.

It is worthwhile noting that a lot of research that goes under the label of ‘degrowth’ is not original but comes down to relabelling existing research, such as on worktime reduction, circular economy, refurbishing houses, or the bioeconomy. This is ironic given the plea for ‘decolonising’ in the degrowth community (Deschner and Hurst 2018).

Why So Many Bad Studies and the Need for Self-Criticism?

One may wonder how it is possible that so many degrowth studies of inferior quality got published. One explanation is that around 100 articles in our sample were published in special issues (14 in total) while another 18 were published by the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), which has been accused of being a predatory publisher (Ángeles Oviedo-García 2021). Another possible explanation is that many reviewers are selected based on their sympathy for degrowth (indicated by past publications promoting it) instead of shown expertise regarding application of methods. Altogether, the journal review process to judge papers was likely more lenient for many degrowth studies than for the average academic article. As a consequence, published research on degrowth is dominated by ideology while lacking scientific quality.

Through drawing attention to several weaknesses in the way research on degrowth is undertaken, our review suggests the need for a healthy degree of self-criticism and modesty in the degrowth community. The research should become more ambitious in terms of case study selection to assure that local- or region-scale studies are complementary and representative. In turn, this will allow for generalisation or upscaling of findings to arrive at a credible global picture. To further contribute to this goal, also more studies are needed of a systemic nature – to assess the relative role of scale versus substitution and efficiency as well as to determine indirect economic, social, and environmental effects, notably energy/carbon rebound. Next, for degrowth research to be taken more seriously, it is essential that it sets higher standards for size and representativeness of samples in empirical studies, investigates public and stakeholder support of degrowth thinking, and strives for synergy with existing research fields (e.g. economics, psychology, policy studies) as these offer a wealth of insights about designing effective, efficient, and equitable environmental/climate policy that can count on sufficient public support.

See original post for references