Miles Davis didn’t put out any studio albums from 1973 until the middle of 1981. In explaining the reasons for this lacuna in his recording career, Milesologists can point to a variety of factors in the man’s professional and personal life. But one in particular looms large: the failure of his 1972 album On the Corner. Davis wasn’t known for occupying any one style of jazz for very long, to put it mildly, but the On the Corner sessions find him very nearly breaking with jazz itself. In a bid to recapture the attention of young black listeners, he took the plunge into a mix of what he later described as “Stockhausen plus funk plus Ornette Coleman.”

“Miles wanted the kids who were into rock,” writes JazzTimes’ Colin Fleming. “That was the target demo, an audience he’d been courting since 1970’s Bitches Brew. He played for that audience on the psychedelic ballroom circuit, doing so with rock groups — the Steve Miller Band, for instance — that he had no respect for as musicians. Davis thought he was slumming it while sharing such bills, but he also believed in the listening skills of youth, which is usually a wise thing to do.” “The resulting, seemingly incongruous mix of musical experiences and desires led him and a host of collaborators — including Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, and James Mtume — to make ‘one holy hell of a grooving, minimalist racket.’”

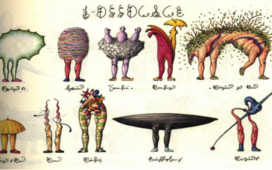

Upon its release, On the Corner “was derided as an affront to taste, an insult to listeners, a sham perpetuated by a man who wanted to rub your face in something most unpleasant, just because he thought he could.” And yet, hearing it in this era — as I did not long ago while listening through Davis’ entire discography — you’d struggle to understand the source of the offense. Indeed, a twenty-first-century listener may well be more troubled by Corky McCoy’s infamous cover art, with its stereotypical street scene whose characters range from prostitute to pimp, hustler to homosexual. The image has been described as “ghettodelic,” a word that could also label the inchoate musical subgenre Davis was attempting to forge.

The culture has long since caught up with the particular sonic experiment run in On the Corner, which “has been hailed in recent years as the album that helped birth hip-hop, funk, post-punk, electronica, and just about any other popular music with a repetitive beat, which was quite the feat for a record that not many people have ever listened to.” But if you join those ranks, you can hardly avoid noticing the textures its sonic collage shares with popular genres of the past few decades, thanks not least to the splicing, and looping that was the specialty of producer Teo Macero (also Davis’ collaborator on Sketches of Spain, In a Silent Way, and Bitches Brew). Maybe, when all this proved to be a bit much for the early seventies, Davis had no choice but to take a break, having finally gotten a few too many miles ahead.

Related Content:

Hear a 65-Hour, Chronological Playlist of Miles Davis’ Revolutionary Jazz Albums

Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew Turns 50: Celebrate the Funk-Jazz-Psych-Rock Masterpiece

The Night When Miles Davis Opened for the Grateful Dead (1970)

Miles Davis’ Entire Discography Presented in a Stylish Interactive Visualization

Miles Davis Opens for Neil Young and “That Sorry-Ass Cat” Steve Miller at The Fillmore East (1970)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.