By Camilla Sandoval, Program Coordinator, Maryland Humanities

A note on language—Latine is a gender-neutral term used by some to refer to folks of Latin American descent. This term will be used here unless quoting or paraphrasing other sources.

Last month, Latinos in Heritage Conservation, a national cultural heritage preservation group, released its Endangered Latinx Landmarks list. The sole East Coast site featured on the list is the historic Unity Mural in D.C. Painted on the side of the PEPCO Substation No. 25 building in 1982, the mural is significant due to its “imagery reflect[ing] Latinx cultural heritage and was designed to unite Latinx and African American youth during a period of racial tension.” The building itself was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2019 for its significance related to architecture and engineering, but the nomination form makes no mention of the mural. At the time of listing, the mural was only 37 years old – below the National Register’s usual 50-year threshold for determining historic significance – which may explain why it was not considered part of the building’s significance. Now, PEPCO Substation No. 25 is scheduled for renovation and would demolish the very wall the mural is painted on. While efforts by D.C.-based cultural organization, Hola Cultura, and others to save this mural have been ongoing since 2018, the Unity Mural reminds us that when we fail to make space for a community’s complexities, we risk losing the physical manifestations of its history and culture.

The Unity Mural’s imagery serves as a powerful symbol of solidarity and the diverse Latine identity in Washington, D.C.. It was designed to be a beacon of light, intended to foster communication and unity among minority cultures and ease racial tensions. The artwork is seen as an exemplification of harmony and unification expressed through unique art and a testament to the cultural richness of the community.

The process of preserving a place is a process of creating a historical narrative. So how has this national storyteller – the National Register, ostensibly our list of “places worthy of preservation” – captured the history and contributions of the Latine community, whose influence and contributions in our own local area are hard to miss? If we were to turn to the National Register to explore this community’s history, we’d come up with an incomplete understanding. The reasons behind underrepresentation are often structural and long-standing. In this case, we’d need to look at the early days of historic preservation and its establishment of the field’s principles, study how the historical and cultural contributions of Latines across the country are currently covered in the National Register, and assess the actions taken by NPS to address this underrepresentation over the last few decades. For our purposes here, we can start to make sense of the disparities in the National Register by looking at how the local history of Latines intersects with National Register criteria that can, in practice, overlook sites connected to more mobile communities or those whose contributions are still emerging in public recognition.

While more research is needed, the general consensus is that the history of the Latine community in the Washington, DC/Maryland/Virginia region (the DMV) begins in DC, with larger trends eventually pushing the community into the Maryland and Virginia suburbs. In the first half of the 20th century, the Latine community started small. The earliest to make their way to D.C. were diplomats, staff, and their families from Latin American countries who came to work in their respective embassies. The embassies were located in Adams Morgan and Mount Pleasant, and it was in these neighborhoods that the community began to grow. Migrants from Cuba and the Dominican Republic followed in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1970s and 1980s, political instability brought on, in part, by American intervention in Latin America pushed many South and Central Americans to leave their homes and search for safety and stability in D.C. Expanding on the restaurants and businesses opened by the earlier generations, South and Central American migrants continued to establish themselves in the city’s physical landscape through murals, theaters, and community organizations.

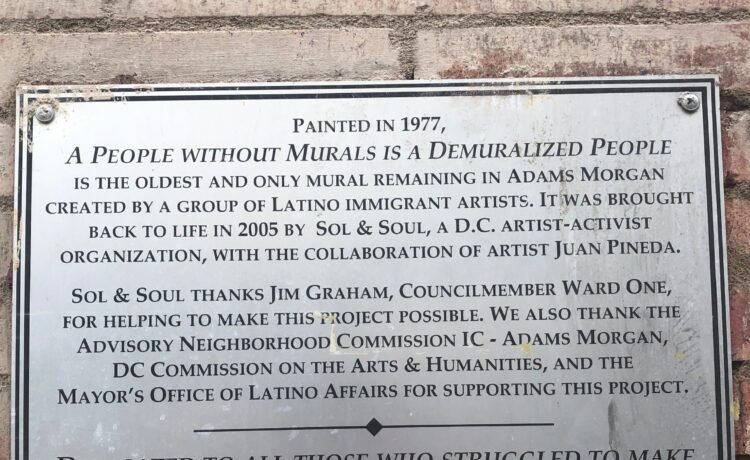

“Un Pueblo Sin Murales es Un Pueblo Dismuralizado” (“A people without murals is a demuralized people”), painted in 1977.

At the same time, the community felt the effects of gentrification. Pushed out by increasing costs of living, Latines started to leave the D.C. neighborhoods where they had built their new lives and made their way to nearby suburbs in Maryland and Virginia. By the 1990s, new waves of Central American migrants skipped D.C. altogether and settled in the counties bordering the city. The harmful consequences of gentrification are not unique to D.C or to this community, but that they took hold just as the community was solidifying its roots created an uphill climb. Preserving these places within the constraints of the federal preservation system has proven especially difficult.

The National Park Service’s searchable table containing properties listed as of June 20, 2025, allows us to take a look at 100,118 National Register listings and sort by state and Area of Significance. When filtering by the categories “Hispanic” and “Ethnic Heritage-Hispanic,” less than 1% of all National Register listings appear. Because the National Park Service only began systematically tracking these categories in recent decades, this figure likely undercounts sites connected to Latine history. Still, the absence of consistent data coding, and the relatively small number of nominations that explicitly frame their significance around Latine heritage, reflects a broader structural issue in how the National Register has historically documented and recognized such histories.

The movement of Latine communities throughout the DMV complicates their recognition within the National Register’s long-standing framework for evaluating historic places. The eligibility of a property is based on its significance, integrity, and – typically – age, though properties less than 50 years old may still qualify under special consideration.[1] Many of the restaurants, murals, and community organizations created by Latines would be excluded because relocation, redevelopment, or the lack of formal documentation makes it difficult to demonstrate integrity or significance within existing guidelines. The community’s removal from its original neighborhoods due to gentrification is a crucial part of this history, complicating continuity of place even as cultural connections persist. While properties may be recognized for their historic associations even after communities move on,[2] identifying and evaluating these associations requires research, documentation, and funding that have often been scarce.

But there are ways forward. Just this year, the DC Preservation League and DC Historic Preservation Office partnered to produce an important historic context study, The History of the Latino Community of Washington, D.C. 1943-1991. The National Register’s guidance on how to apply its criteria to evaluate the significance of a site or property offers some possibilities for these sites to be listed, and the historic context is a critical step towards that recognition – at least in DC. But the development of the Latine community in this time period and geographic setting remains an understudied and underacknowledged topic. The historical and cultural contributions of this community have often been documented by community members themselves, outside of scholarly circles or peer-reviewed publications. Without dedicated ongoing support, we will be left with a system meant to identify “places worthy of preservation” that is incapable of doing so for one of the largest ethnic groups in our region.

[1] A good example of how to approach issues with age constraints is the recently listed Baltimore American Indian Center in Baltimore. The Lumbee community has roots in Baltimore dating to the late 19th century, but the Center’s period of significance (1972-2011) is almost entirely within the past 50 years, beginning when it moved to its current location in 1972. A good model for how we can address these questions from a National Register perspective is the Asian American Communities in Maryland MPDF.

[2] Properties are listed for their historic association, even if that is not their current use. An example of this is Baltimore’s Chinatown, listed in 2024.

References:

Asch, Chris Myers and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Andrade, Xavier. “Without Action, the Unity Mural will be Demolished in 2025.” Hola Cultura, holacultura.com/without-action-the-unity-mural-will-be-demolished/.

Cadaval, Olivia. Creating a Latino Identity in the Nation’s Capital: The Latino Festival. Taylor & Francis, 1998.

“Endangered Latinx Landmarks.” Latinos in Heritage Conservation. www.latinoheritage.us/endangeredlatinxlandmarks.

Sandoval, Camilla. “‘What White Nonsense is This?’ Investigating the Seldom Seen or Heard Stories of Latinxs in the National Register.” MA, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2019.

Smith, Kathryn S., ed. Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation’s Capital. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Sprehn-Malagón, Maria, Jorge Hernandez-Fujigaki, and Linda Robinson. Latinos in the Washington Metro Area. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

“Unity Mural.” Latinos in Heritage Conservation. www.latinoheritage.us/ell-2025-nominations/unity-mural%2C-the-potomac-electric-power-company-(pepco)-substation-no.-25-building.

US Department of the Interior. Guidelines for Evaluating and Nominating Properties that Have Achieved Significance Within the Past Fifty Years. Marcella Sherfy and W. Ray Luce. NPS, National Register Bulletin 22, 1979. www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB22-Complete.pdf.

US Department of Interior. How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. NPS, National Register Bulletin 15, 1990. www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NRB-15_web508.pdf.

US Department of Interior. National Register of Historic Places. NPS. www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/upload/NR_Brochure_Poster_web508.pdf.

US Department of Interior. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form-Potomac Electric Power Company Substation No. 25. NPS, June 2019. npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/93be4d92-db73-4bf8-b24c-bbfd25318e4f.

US Department of Interior. National Register Database and Research. NPS. www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/database-research.htm.

US Department of Interior. Program Updates. NPS, May 2025. www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/program-updates.htm.

Discover more from Our History, Our Heritage

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.