(RNS) — When Ami Doshi was invited as a new migrant from India to friends’ Thanksgiving Day festivities, it shocked the then-middle schooler to hear the meat of a rare, elaborately feathered bird would be on the menu.

“I actually had no idea what a turkey was,” said Doshi, now in her early 40s. But her bigger question was a moral one. “When you kill a bird, they can feel it, they can see it, you know, with all of the five senses, they can experience it,” she said. “Why is a pet’s life more important than a bird’s life?”

Doshi, who was raised in the Jain faith, has been a vegetarian her whole life. Committing to their fundamental tenet of ahimsa, or nonviolence, Jains avoid causing harm to all living beings, whether in thought, word or action. Many avoid eating root vegetables, like onion and garlic, out of reverence for every form of life, including the insects uprooted when the plants are harvested.

It seemed odd to Doshi, she said, that the centerpiece of a holiday dedicated to gratitude would be a roasted and stuffed creature.

For Jain Americans who want to participate in this most American of holidays, an alternative was needed. Jains in the U.S., who number about 200,000, have made the day their own by forging a tradition of attending temple services to pray for the millions of lives lost, serving meals to the needy and cooking up an all-vegan feast.

“We figured out a place for us,” said Nirva Patel, a second-generation Jain American and executive director of the Brooks McCormick Jr. Animal Law & Policy Program at Harvard Law School. “We believe that Thanksgiving is about gratitude, about being present, about family. We kind of pulled the good from that holiday, and we’re doing it in our own curated way.”

Guests enjoy the 2023 Thanksgiving potluck hosted by Nirva Patel. (Photo courtesy of Nirva Patel)

Patel, who executive produced a well-received 2018 vegan lifestyle documentary “The Game Changers,” hosts a plant-based potluck every year, complete with a plastic turkey centerpiece as a conversation starter.

Growing up as a Jain in suburban Massachusetts was complicated this time of year, she said. “It was very, very foreign concept and a very strange thing to see the kids and teachers celebrating a turkey and talking about a turkey’s gobble and coloring printouts of turkeys, but then literally talking about how they carve them up and eat them,” she said. “You just kind of stayed silent in the back of the classroom.”

A former chair of the animal advocacy group Farm Sanctuary, Patel gained a newfound appreciation for the bird when the organization held its own “Celebration for the Turkeys”: a feast of turkey-friendly foods prepared for the rescued guests of honor. “It really makes you think about this beautiful creature that is being so exploited,” she said.

Forcing anyone else to change their beliefs on meat consumption is not the point, said Patel. Accepting multiple viewpoints is another tenet of Jainism, though one that can be difficult to act out either as an activist or at the dinner table.

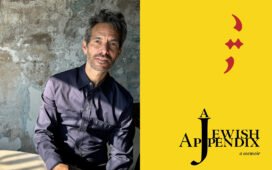

Nirva Patel. (Photo courtesy of Harvard)

“Getting people on board is really about having convictions of your own self, your own beliefs and being unapologetic about it, but also not being harsh and rude about it,” she said. “The best thing we can do is just be as compassionate as possible in our thoughts, in our actions, (and) realize that everything starts with what’s on your plate.”

Rahul Jain, a consultant in the Washington area who moved to America 25 years ago, said it took Jains time to adopt Thanksgiving. Many chose at first to participate in a ritual fast called Ayambil, in which devotees consume only simple, bland foods in the practice of spiritual discipline. Others, said Jain, would attend prayer services at one of the 72 nationwide Jain centers, chanting a mantra asking for forgiveness for the fate of the 50 million turkeys who are slaughtered each year.

Both practices remain common, said Jain, but in the past decade, younger generations of Jains have begun to celebrate the holiday more traditionally, likening it to the Jain festival of Paryushana, during which the last day is dedicated to expressing gratitude for friends and family.

“If you put the food aside, the concept of giving thanks is quite remarkable,” he said. “It resonates well with the Jain principle of aparigraha, which is nonattachment: Don’t get too attached to one thing, one person, one job. That kind of rings true with, ‘Did you give thanks?’ You’re saying, ‘I am grateful for what I have. I don’t need more.’”

The vegetarian feasts can be complemented with a nightlong prayer, and combined with a side of backyard football. “I can’t change every single human being in the world to match with my ideas,” said Jain. “And that’s OK. As long as we can all live in harmony and peace is what Jainism stands for, and that’s the message we want to convey.”

Sulekh Jain, a Jain community leader, came to the U.S. for the first time in the 1960s, when Jain residents were relatively few, with no organizational infrastructure or even temple to attend. The now retired aerospace engineer “started from scratch,” co-founding the JAINA, the umbrella organization for all Jain societies across the country, in 1980.

But with the rising popularity of veganism, animal rights advocacy and cruelty-free awareness, he said, “every day has gotten easier and easier to follow Jain values.”

“It is very difficult for me to preach,” said Jain, who lives in Las Vegas. “I don’t want to hurt somebody in their own sensibility. But, what are we giving thanks for?” he said.

A bright pumpkin soup adorns a table. (Photo by Katrin Bolovtsova/Pexels/Creative Commons)

Jain regrets that the Thanksgiving holiday, thanks to creeping commercialism, has moved away from the principle of gratitude. “When we say ‘Happy Thanksgiving,’ let’s make that happy Thanksgiving a reality, and save this environment and save this planet.” Meat production, he notes, is a large contributor to climate change.

Manish Mehta, chair of JAINA’s diaspora committee, said Jains are increasingly concerned about “our carbon footprint, and our karmic footprint.” He participates in vegan food drives throughout the year that distribute hundreds of thousands of meals to the needy. In its own celebrations, such as shared Diwali meals, his Jain community in Michigan is careful to use biodegradable cutlery. “There is more care taken about how we cook food and how we avoid food waste, and reducing what goes into landfills.”

Their choices on Thanksgiving Day are an extension of that sensibility. “Jains are trying to evolve practices and adapt to a North American lifestyle,” he said, keeping their own traditions alive while contributing to American society.

After all, “for us,” he says, “compassion is kind of in our DNA.”