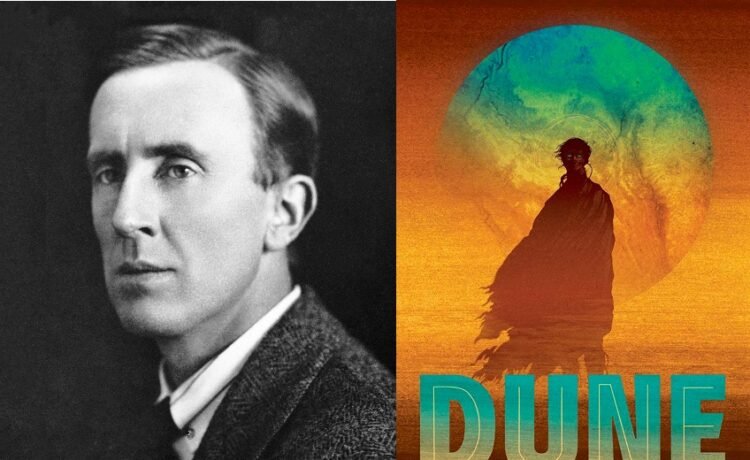

One can easily imagine a reader enjoying both The Lord of the Rings and Dune. Both of those works of epic fantasy were published in the form of a series of long novels beginning in the mid-twentieth century; both create elaborate worlds of their own, right down to details of ecology and language; both seriously (and these days, unfashionably) concern themselves with the theme of what constitutes heroic action; both have even inspired multiple big-budget Hollywood spectacles. The reader equally dedicated to the work of J. R. R. Tolkien and Frank Herbert turns out to be a more elusive creature than we may expect, but perhaps that shouldn’t surprise us, given Tolkien’s own attitude toward Dune.

“It is impossible for an author still writing to be fair to another author working along the same lines,” Tolkien wrote in 1966 to a fan who’d sent him a copy of Herbert’s book, which had come out the year before. “In fact I dislike DUNE with some intensity, and in that unfortunate case it is much the best and fairest to another author to keep silent and refuse to comment.”

That lack of elaboration has, if anything, only stoked the curiosity of Lord of the Rings and Dune enthusiasts alike, as evidenced by this thread from a few years ago on the r/tolkienfans subreddit. Was it the materialism and Machiavellianism implicit in Dune’s worldview? The preponderance of invented names and coinages that surely wouldn’t meet the etymological standard of an Oxford linguist?

Maybe it was the aristocratic isolation — a kind of anti-fellowship — of its protagonist Paul Atreides, who comes to possess the equivalent of Tolkien’s Ring of Power. “In Dune, Paul willingly takes the (metaphorical) ring and wields it,” writes Evan Amato at The Culturist. “He leads, transforms, and conquers. The universe bends to his vision. He suffers for it, yes, and questions it, but he never truly rejects the call to rule. Contrast this with the world of Middle-earth, where all Tolkien’s heroes do the opposite. When Frodo offers the Ring to Aragorn, he refuses. Even Samwise, humble as he is, feels the surge of the Ring’s power, and lets it go.” Assuming he managed to get through the first Dune novel, Tolkien could hardly have approved of the narrative’s moral arc. Whether his or Herbert’s vision puts up the more realistic allegory for humanity’s lot is another matter entirely.

Related Content:

Frank Herbert Explains the Origins of Dune (1969)

J. R. R. Tolkien Writes & Speaks in Elvish, a Language He Invented for The Lord of the Rings

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.