The wave of solidarity with Gaza that has swept across western Europe over the past months stops at the borders of the Czech Republic, where most people seem unconcerned by the plight of the Palestinians. This is an attitude it shares with the Slovakia, Poland and Hungary.

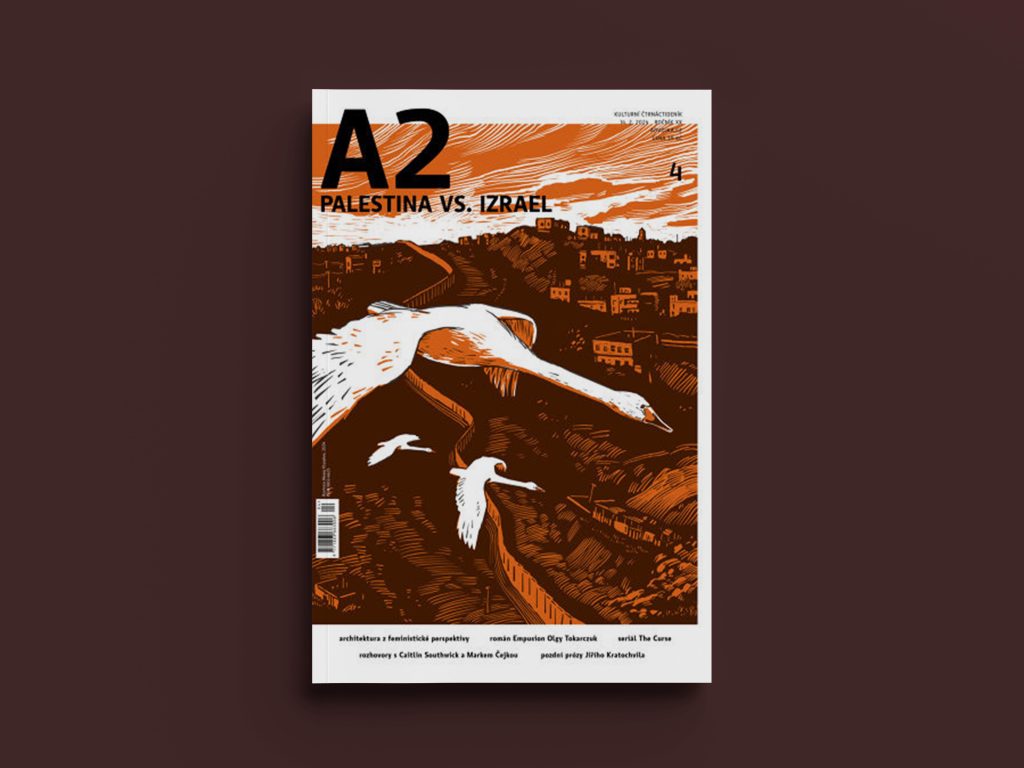

The Czech journal A2 explores the reasons for the staunch support for Israel on the part of the Czech government, public and media, in order to understand why, as A2 editor Lukáš Rychetský puts it, ‘we seem to feel the need to escape from the complexity and ambiguity of conflicts such as the Israeli–Palestinian one, into a narrative about a clash between Good and Evil.’

The Czech–Israeli relationship

Political scientist Marek Čejka, a specialist in Israel’s modern history, explains that to understand Czech attitudes to the Israel–Palestine conflict one must go back to the antisemitic Hilsner trial at the turn of 20 century. Czechoslovakia’s future president Tomáš Masaryk, then a law professor, defended Leopold Hilsner, a Jew accused of blood libel (Hilsner was sentenced anyway). As head of state, Masaryk became a vocal supporter of Zionist aspirations, which he regarded as an emancipation movement akin to the Czech and Slovak striving for independence.

Except for a brief interlude after World War II, Czechoslovakia followed the Soviet policy of supporting the Arab countries throughout the communist era. During Václav Havel’s presidency, Czechoslovak (and later Czech) policy reversed, although as Čejka points out, Havel supported the peace process and made a point of meeting Palestinians whenever he visited Israel. After Havel, however, the Czech right forged close links with Likud, strengthening Israeli–Czech ties.

Čejka finds it startling that the current Czech cabinet ‘has shown no reflection of the mass protests against Netanyahu’s government at a time when it has clearly shifted towards authoritarianism and tried to push through undemocratic changes in the Israeli political system’. He notes that, more recently, the Czech Republic and Hungary went as far as to block EU sanctions against radical Israeli–Jewish settlers.

Censorship and media bias

Despite the nuanced portrayal of the Israel–Palestine conflict in half a dozen works by Israeli writers that have been published in Czech translation, writes Lukáš Rychetský, it would appear that Czech perceptions are still shaped by Leon Uris’s 1958 pro-Zionist bestseller Exodus (published in Czech in 1991). Far fewer works by Palestinian authors have been translated into Czech, writes Monika Šramová, who notes the centrality of the themes of displacement and exile in Palestinian literature.

The bias is even more evident in the Czech media, writes media theorist Jan Motal. Palestinians, and those defending their rights, are demonised or depersonalised, and unlike Israeli victims, are rarely profiled. Motal cites the example of the Czech-based Palestinian artist Yara Abu Aataya, whose story was first featured by mainstream TV stations and newspapers, only to be quickly withdrawn, with the journalists who interviewed her losing their jobs.

The fact that many Palestinian journalists have been killed, injured or driven into exile seems to have left their Czech colleagues unmoved. At any rate, they have been unwilling to respond to calls from the International Federation of Journalists to support them.

‘Czech journalism has for a long time suffered from being isolated from the global debate on journalist ethics and standards’, comments Motal. ‘Although attempts to remedy this failure have been made, particularly by smaller, independent media, the mainstream has remained doggedly resistant. The dehumanisation or ignoring of the Palestinian victims of the war in Gaza is just one fragment of the unflattering image of Czech journalism that is still incapable of standing up for human dignity.’