The USMCA trade agreement, now in its fifth year of existence and up for renegotiation in 2026, is already looking frail.

Yesterday (Nov 25), US President-Elect Donald Trump announced that on his first day back in office he would use executive powers to impose a 25% tariff on all products entering the US from Mexico and Canada, its USMCA partners, as well as an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports. Those tariffs, he said, will remain in place until the flow of fentanyl and illegal immigrants into the US is halted.

— Donald J. Trump Posts From His Truth Social (@TrumpDailyPosts) November 26, 2024

Predictable as this announcement may have been, it still raises lots of (largely unanswerable) questions.

Will the Trump administration apply the tariffs across the board, as Trump’s message strongly suggests, or will it be more judicious in their application? In 2018, the Trump administration prioritised tariffs on intermediate goods to avoid hurting consumers. What will the broader economic effects be this time round? How severe will their impact be on inflation, economic activity and product shortages in the US, given this new round of tariffs will be levied not just on China but also the US’ other two biggest trade partners (Mexico and Canada)?

Is the US even ready or capable of reindustrialising in the targeted sectors? Six years after Trump began his trade war on China, the US may have diversified its imports away from China for low value-added goods (e.g. bedding, mattresses, and furniture), but diversification for higher value-added goods (e.g. smart phones, portable computers, lithium-ion batteries) is proving far harder, data from the Atlantic Council (of all places) suggests.

There are also serious questions about the legality of Trump’s proposed tariffs. Will Canada and Mexico retaliate with their own tit-for-tat tariffs? If so, just how badly could the resulting trade war spiral? Will it push the three countries into recession? How badly will it hit the Mexican peso, which has already faced significant depreciation so far this year? What will the legal consequences be? Lastly, how will the tariffs on Mexican and Canadian goods help the US tackle its opioid and fentanyl epidemic if precious little is done on the demand side of the equation?

“What tariffs should we put on their merchandise until they stop consuming drugs and illegally exporting weapons to our homeland?” asked the president of Mexico’s Senate, Gerardo Fernández Noroña.

One thing that is clear is that trilateral relations between the erstwhile “Three Amigos” of North America are about to become a lot more strained — for a while at least.

That said, the long-term impact may not be as severe as some are fearing. When Trump began his first presidential term, it was generally assumed that it would be disastrous for Mexico’s economy. Yet more or less the opposite occurred: the Trump administration’s trade war on China and resulting nearshoring strategy helped turn Mexico into the US’ largest trade partner.

Also, this is not the first time Trump has threatened to impose tariffs on Mexico. In 2019, he said he would impose a 5% tariff on all goods entering from Mexico unless it stemmed the flow of illegal immigration to the United States. Nine days later, Trump ditched the plan after Republican senators had threatened to try to block the tariffs if he moved ahead with them.

Canada Turns On Mexico

This time round, however, it’s not just Trump that’s talking tough on North American trade. A couple of weeks ago, Doug Ford, the premier of Ontario, Canada’s richest province, called for Mexico’s removal from the USMCA trade agreement due to its growing trade and diplomatic ties with China (a topic we covered just a couple of months ago).

“Since signing on to the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, Mexico has allowed itself to become a backdoor for Chinese cars, auto parts and other products into Canadian and American markets, putting Canadian and American workers’ livelihoods at risk while undermining our communities.”

Ford’s position is far from an isolated one. Danielle Smith, the premier of Alberta, Canada’s third richest province, expressed a similar view just days later, noting that “Mexico has taken a different direction” and that Americans and Canadians want to have “a fair trade relationship.” Chrystia Freeland, Deputy Prime Minister of Canada, said she shares the concerns of the United States regarding Mexico’s relationship with China.

The same apparently goes for Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Last Thursday, just three days after meeting with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum on the side lines of the G20 meeting in Rio, he told a press conference that the USMCA would ideally continue as a trilateral trade deal, but hinted that if Mexico did not tighten its policy against China, other alternatives would have to be sought.

“We have an absolutely exceptional trade agreement at the moment,” Trudeau said. “We will guarantee Canada’s jobs and growth in the long term. Ideally, we would do it as a united North American market, but, pending the decisions and choices that Mexico has made, we may have to consider other options.”

Politicians in the United States and Canada have expressed growing concerns that under the USMCA, Chinese companies could assemble cars in Mexico and ship them north, which would spare them tariffs. In recent years, China has poured huge sums of money into Mexico to build factories and automotive plants. And trade is booming between the two countries.

Between 2010 and 2022 Mexico’s imports of goods from China more than doubled, from $45 billion to $119 billion. Recent data suggest that imports from China account for roughly one-fifth of all of Mexico’s imports, according to El Financiero. That’s up from around 15% in 2015. During the same period, the US’ share of Mexican imports has fallen from 50% to 44%, even as the US and Mexico last year became each other’s largest trade partner, for the first time in 20 years.

The Canadian government is also up in arms about the Sheinbaum government’s plans to radically rewrite Mexico’s mining laws. For over three decades, Mexico has been a veritable paradise for global mining conglomerates, many of them based in Canada, serving up some of the laxest regulations in Latin America. That is now changing. The proposed reforms include a near-total ban on open-pit mining and much stricter restrictions on the use of water in areas with low availability. Just this week, Mexico’s finance ministry (SHCP) has proposed increasing mining royalties in the federal budget bill for 2025.

Canada’s proposals to eject Mexico from USMCA have an ironic twist given it was Mexico’s AMLO government that allegedly intervened to helped seal Canada’s membership of the USMCA. By late 2018, relations between Trump and Trudeau had soured to the point where Trump was threatening to leave Ottawa out of the trade deal altogether after already signing a preliminary agreement with Mexico. But AMLO apparently managed to convince Trump to include Canada in a three-way deal.

Six years later, Trudeau has repaid the favour by threatening to throw Mexico under the bus in a blatant attempt to ingratiate himself with Trump. Other factors are at work, including electoral considerations (for both Trudeau and province premiers like Ford) and economic drivers.

Competing for the Same Prize

Mexico and Canada may be USMCA partners but they are ultimately competing for the same prize: US market share. By contrast, the trade between the two countries is relatively modest. In the first three-quarters of 2024, Canada sold $309 billion worth of goods and services to the US and just $9.6 billion to Mexico. And while Canada has a trade surplus with the US, its trade balance with Mexico is constantly in negative territory. In the first nine months of this year alone, it has clocked up a trade deficit with Mexico of $4.28 billion.

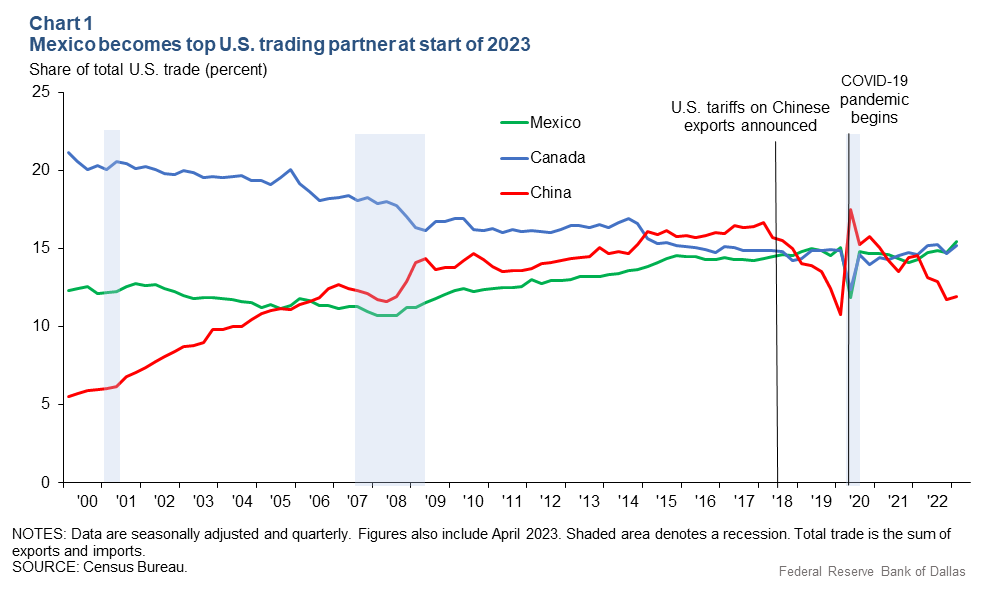

More important still, since the signing of the USMC, Canada’s trade with the US has more or less stagnated. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that in 2018, Canada’s share of imports from the US has barely budged. Meanwhile, Mexico has overtaken both China and Canada to become the US’ main trade partner, primarily as a result of the nearshoring trend sparked by the US’ trade war with China during the first Trump administration.

So, the combination of USMCA, Trump’s tariffs on China and the nearshoring trend it helped set in motion has been a boon for Mexico’s manufacturing sector, attracting billions in investment and creating millions of jobs, while doing little for Canada’s trade with the US. Given as much, it is perhaps not so surprising that some of Canada’s most powerful politicians are calling for the scrapping of USMCA. By taking Mexico out of the equation, the United States and Canada could then update their 1988 bilateral treaty, which is apparently still in force.

The Mexican government initially responded to the threats from its two USMCA partners by trying to assuage their concerns that Mexico would be used as a backdoor for China while at the same time insisting that it would not sacrifice its growing trade relations with China. Deputy Mexican Foreign Trade Minister Luis Rosendo Gutierrez last month said Mexico would continue to prioritise the U.S. and Canada due to their strategic alliance through USMCA, but that did not imply Mexico would “break with China” or “deny them investments in Mexico.”

But the more recent threats appear to have struck a nerve. This week, Mexico’s Secretary of Economy, Marcelo Ebrard, said he would propose a Plan B on China to the United States to strengthen North American productivity and reduce dependence on Chinese parts and components:

In short, until now, we do have or have had certain common visions or, at least, certain common appreciations; but we have not had a Plan B. And maybe Mexico can put that on the table, not be on the defensive but propose it. In fact, we are already working with many companies [on this].

To what end? To reduce the volume of our imports not only from China but from Asia as a whole, because we have seen an exponential growth of imports from several countries in Asia, not only from China. So, we have to increase our national content, but we have to work with the companies that export, which are part of the circuit that I am describing right now.

In its Work Plan for the period 2024-2030, Mexico’s Ministry of Economy indicates that the federal government has already begun working with companies with big operations in Asia, including Foxconn, Intel, General Motors, DHL and Stellantis, to identify products that can be manufactured in Mexico.

It’s also worth recalling that in April Mexico imposed tariffs of between 5% and 50% on imports of 544 imported products, including footwear, wood, plastic, furniture, and steel, from countries with which it does not have a trade agreement. As we noted at the time, the tariffs had one clear target in mind: imports from China, Mexico’s second largest trade partner, though the word “China” was not mentioned once in the presidential decree.

In other words, given the scale of the economic stakes for Mexico, with just over 80% of all its exports destined for the US market, it’s likely that the Sheinbaum government, like the AMLO government before it, will eventually accommodate US demands. In recent days, the ruling Morena party has even agreed to rewrite recently proposed laws aimed at eliminating a half-dozen independent regulatory and oversight agencies in order to precisely mimic the minimum accepted requirements under the trade accord.

But the Mexican government has also threatened to impose retaliatory tariffs against the US. And that is likely to hit sales of US producers in Mexico, lowering incomes and shrinking output further.

“If you put 25% tariffs on me, I have to react with tariffs,” said Ebrard a couple of weeks ago. “If you apply tariffs, we’ll have to apply tariffs. And what does that bring you? A gigantic cost for the North American economy.”

On Friday, the investor-state dispute panel into Mexico’s ban on GMO corn for human consumption is scheduled to publish its ruling. As we reported a couple of weeks ago, recent statements from senior officials in Mexico, including Ebrard, suggest that the panel will rule in the US’ favour. As a result, Mexico will face the starkest of choices: withdraw its 2023 decree banning GM corn for human consumption — or face stiff penalties, including possibly sanctions.

If the rumours prove true, the Sheinbaum government is likely to face similar legal challenges to many of the other sweeping constitution reforms it plans to pass in the coming months, including of the mining sector, housing, water management, energy and workers’ rights. As we noted, while the Mexican economy may have benefited enormously from rising trade with the US over the past five years, the price tag is growing as it becomes harder and harder to legislate in ways that benefit the people but harm the interests of US or Canadian businesses.

At the same time, trade with the US is guaranteed to suffer as Trump’s tariffs hit their mark. In other words, the benefits of USMCA membership are likely to recede in the coming months for all involved while the costs are likely to rise. And that is hardly the foundation for a healthy, long-term relationship.