Zaha Hadid died in 2016, at the age of 65. She certainly wasn’t old, by the standards of our time, though in most professions, her best working years would already have been behind her. She was, however, an architect, and by age 65, most architects are still very much in their prime. Take Rem Koolhaas, who today remains a leader of the Office of Metropolitan Architecture in his eighties — and who, back in the seventies, was one of Hadid’s teachers at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London. It was there that Koolhaas gave his promising, unconventional student the assignment of basing a project on the art of Kazimir Malevich.

Specifically, as architect Michael Wyetzner explains in the new Architectural Digest video above, Hadid had to adapt one of Malevich’s “arkhitektons,” which were “objects that took his ideas of shapes that he used in his paintings” — the most widely known among them being Black Square, from 1915, previously featured here on Open Culture — “and turned them into a 3D piece.”

To understand Hadid’s formation, then, we must go back to the early-twentieth-century Russia in which Malevich operated as an avant-garde artist, and in which he launched the movement he called Suprematism, whose name reflects “the idea that his art was concerned with the supremacy of pure feeling, as opposed to the representation of the real world.”

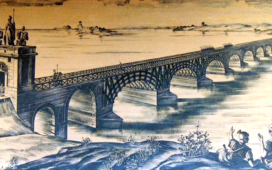

As a pioneer of “non-objective” art, Malevich did his part to inspire Hadid on her path to designing buildings that come as close to abstraction as technologically possible. In fact, during the initial phases of Hadid’s career, what we think of as her signature curve-intensive architectural style — exemplified by buildings like the London Aquatics Centre and the Dongdaemun Design Plaza in Seoul — wasn’t technologically possible. Examining her early paintings, such as the one of the arkhitekton-based bridge hotel she turned in to Koolhaas, or her first built projects like the Vitra Fire Station in Weil am Rhein, shows us how her ideas were already evolving in directions then practically unthinkable in architecture. Zaha Hadid has now been gone nearly a decade, but her field is in many ways still catching up with her.

Related content:

An Introduction to the World-Renowned Architect Zaha Hadid, “the Queen of the Curve”

What Makes Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915) Not Just Art, But Important Art

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.