In the credits of Phil Collins’ No Jacket Required appears the disclaimer that “there is no Fairlight on this record.” Cryptic though it may have appeared to most of that album’s many buyers, technology-minded musicians would’ve got it. In the half-decades since its introduction, the Fairlight Computer Musical Instrument, or CMI, had reshaped the sound of pop music — or at least the pop music created by acts who could afford one. The device may have cost as much as a house, but for those who understood the potential of playing and manipulating the sounds of real-life instruments (or of anything else besides) digitally, money was no object.

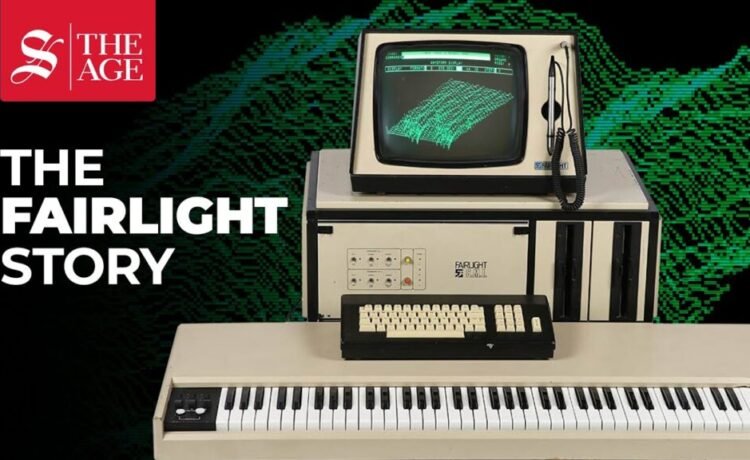

The history of the Fairlight CMI is told in the video above from the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, incorporating interviews from its Australian inventors Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie. According to Ryrie, No Jacket Required actually did use the Fairlight, in the sense that one of its musicians sampled a sound from the Fairlight’s library. To musicians, using the technology not yet widely known as digital sampling would have felt like magic; to listeners, it meant a whole range of sounds they’d never heard before, or at least never used in that way. Take the “orchestra hit” originally sampled from a record of Stravinsky’s The Firebird (and whose story is told in the Vox video just above), which soon became practically inescapable.

We might call the orchestra hit the Fairlight’s “killer app,” though its breathy, faintly vocal sample known as “ARR1” also saw a lot of action across genres. A desire for those particular effects brought a lot of musicians and producers onto the bandwagon throughout the eighties, but it was the early adopters who used the Fairlight most creatively. The earliest among them was Peter Gabriel, who appears in the clip from the French documentary above gathering sounds to sample, blowing wind through pipes and smashing up televisions in a junkyard. Kate Bush embraced the Fairlight with a special fervor, using not just its sampling capabilities but also its groundbreaking sequencing software (included from the Series II onward) to create her 1985 hit “Running Up That Hill,” which made a surprise return to popularity just a few years ago.

The Fairlight’s high-profile American users included Stevie Wonder, Todd Rundgren, and Herbie Hancock, who demonstrates his own model alongside the late Quincy Jones in the documentary clip above. With its green-on-black monitor, its gigantic floppy disks, and its futuristic-looking “light pen” (as natural a pointing device as any in an era when most of humanity had never laid eyes on a mouse), it resembles less a musical instrument than an early personal computer with a piano keyboard attached. It had its cumbersome qualities, and some leaned rather too heavily on its packed-in sounds, but as Hancock points out, a tool is a tool, and it’s all down to the human being in control to get pleasing results out of it: “It doesn’t plug itself in. It doesn’t program itself… yet.” To which the always-prescient Jones adds: “It’s on the way, though.”

Related content:

Watch Herbie Hancock Demo a Fairlight CMI Synthesizer on Sesame Street (1983)

How the Yamaha DX7 Digital Synthesizer Defined the Sound of 1980s Music

Thomas Dolby Explains How a Synthesizer Works on a Jim Henson Kids Show (1989)

How the Moog Synthesizer Changed the Sound of Music

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.