Listening to music, especially live music, can be a religious experience. These days, most of us say that figuratively, but for medieval monks, it was the literal truth. Every aspect of life in a monastery was meant to get you that much closer to God, but especially the times when everyone came together and sang. For English monks accustomed to that way of life, it would have come as quite a shock, to say the very least, when Henry VIII ordered the dissolution of the monasteries between the mid fifteen-thirties and the early fifteen-forties. Not only were the inhabitants of those refuges sent packing, their sacred music was cast to the wind.

Nearly half a millennium later, that music is still being recovered. As reported by the Guardian’s Steven Morris, University of Exeter historian James Clark found the latest example while researching the still-standing Buckland Abbey in Devon for the National Trust.

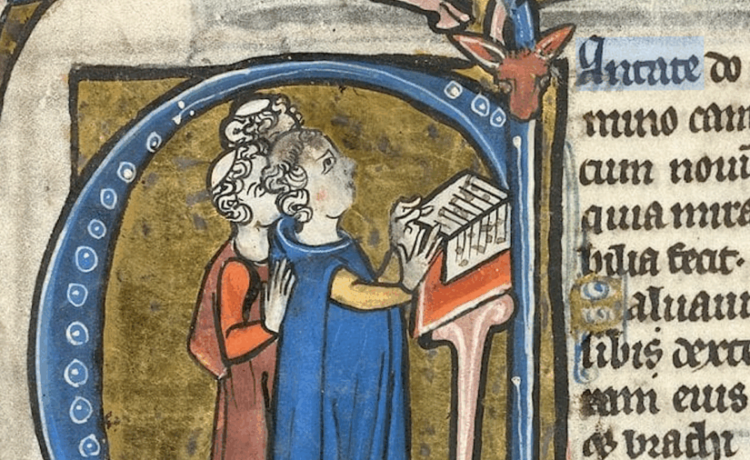

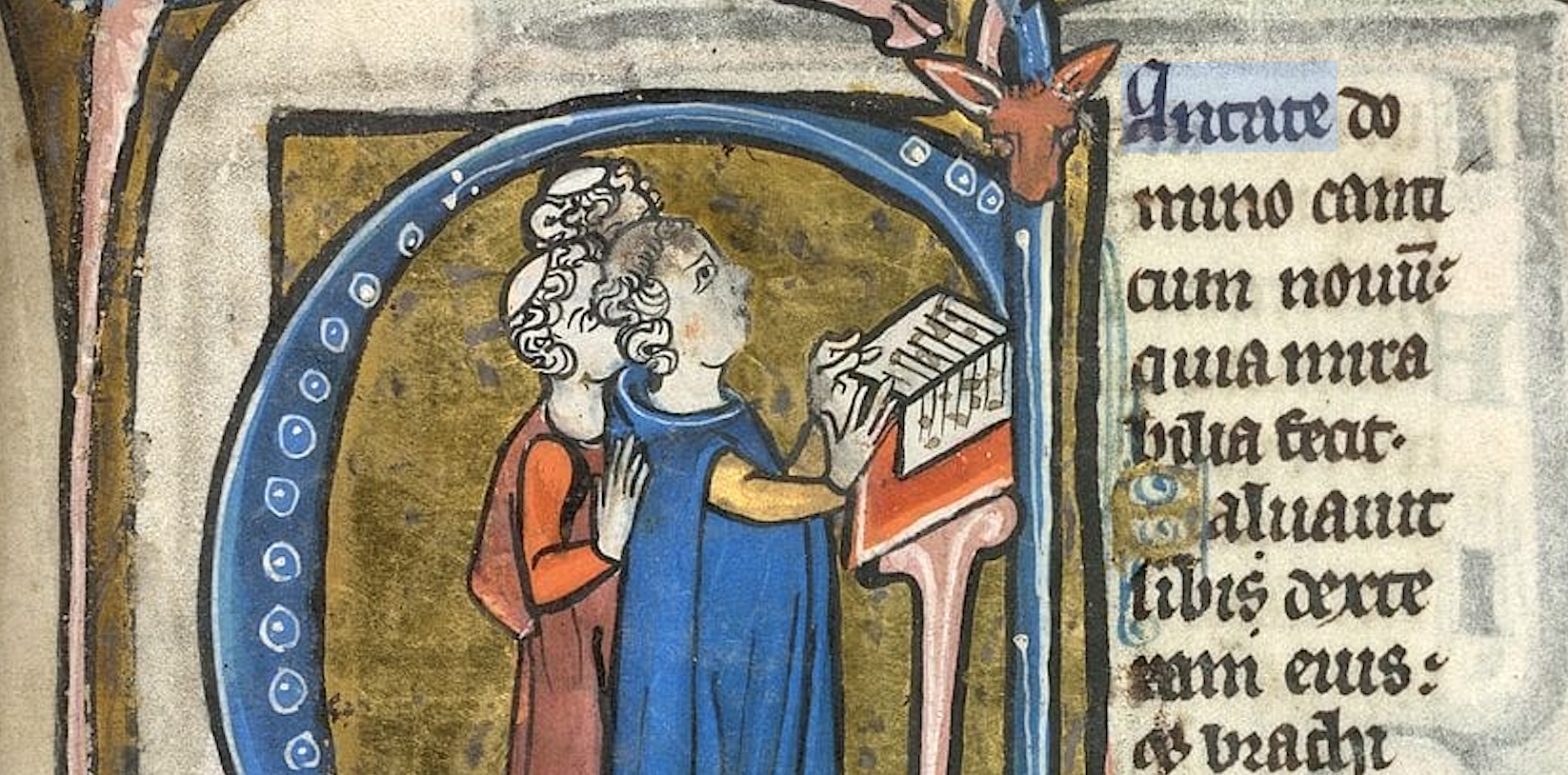

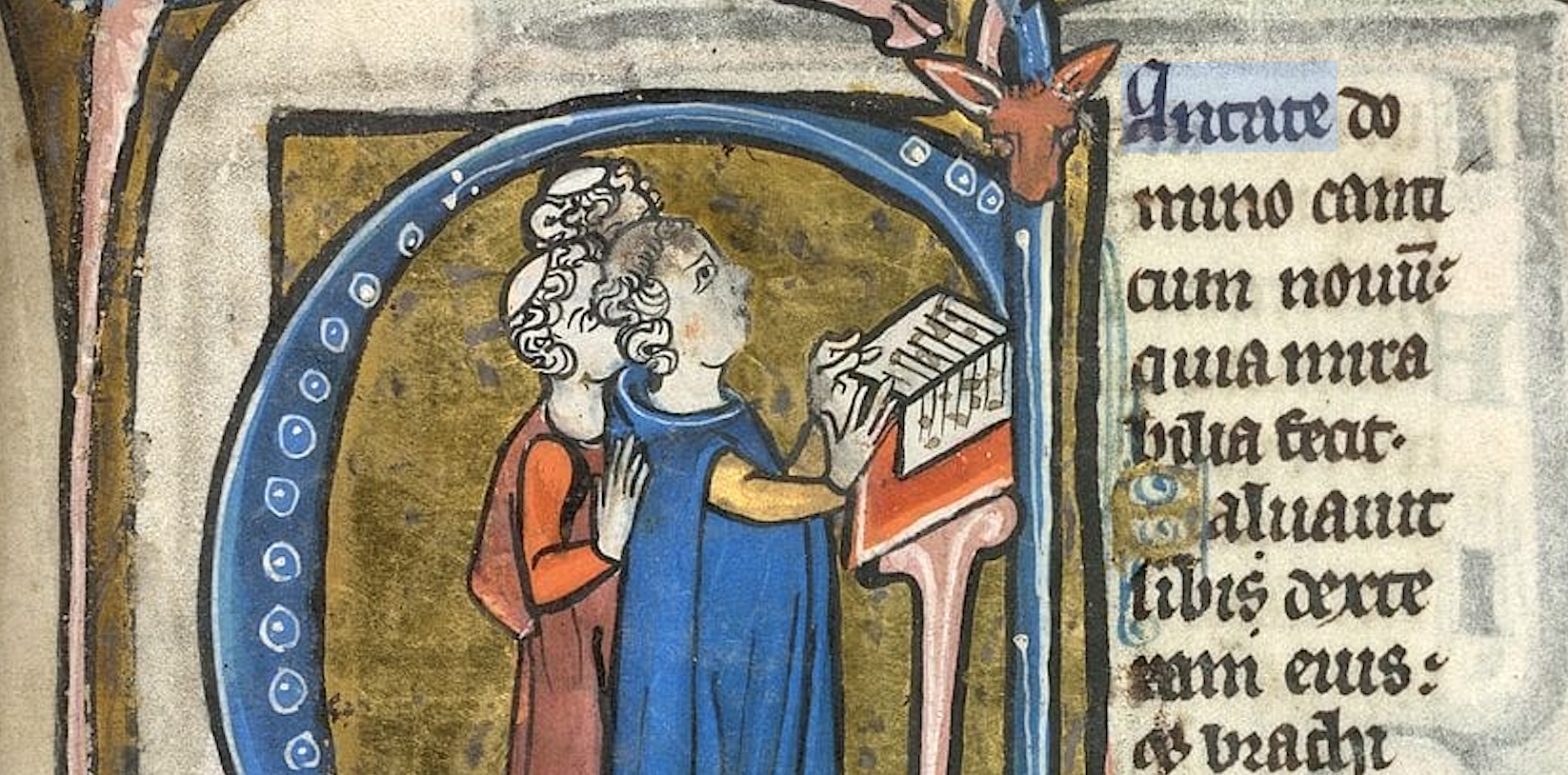

“Only one book — rather boringly setting out the customs the monks followed — was known to exist, held in the British Library.” But lo and behold, a few leaves of parchment stuck in the back happened to contain pieces of early sixteenth-century music, or rather chant, with both text and notation, a vanishingly rare sort of artifact of medieval monastic life.

Just this month, for the first time in almost five centuries, the music from the “Buckland book” resonated within the walls of Buckland Abbey once again. You can hear a clip from the University of Exeter chapel choir’s performance just above, which may or may not get across the grimness of the original work. “The themes are heavy — the threats from disease and crop failures, not to mention powerful rulers — but the polyphonic style is bright and joyful, a contrast to the sort of mournful chants most associated with monks,” writes Morris. For listeners here in the twenty-first century, these compositions offer the additional transcendental dimension of aesthetic time travel. The only way their rediscovery could be more fortuitous is if it had happened in time to benefit from the nineteen-nineties Gregorian-chant boom.

Related content:

See the Guidonian Hand, the Medieval System for Reading Music, Get Brought Back to Life

The Medieval Ban Against the “Devil’s Tritone”: Debunking a Great Myth in Music Theory

A Beatboxing Buddhist Monk Creates Music for Meditation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.