The Harris Walz plan for reining in grocery prices appears to contain two components, one of which has attracted a lot of attention (stopping price gouging), while the second (antitrust against food processors) has garnered less criticism (see agenda here). While it might be the case that grocery store chains are exploiting some monopoly power, it’s not clear to me it’s the most important aspect of grocery price developments.

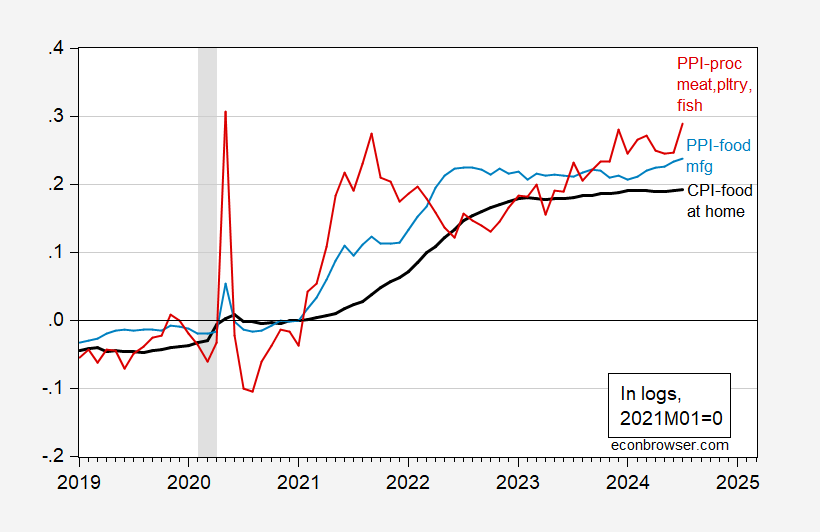

Here’s a picture of food-at-home retail prices vs. wholesale manufacturing food prices (as well as processed meat prices), all normalized in logs to 2021M01=0.

Figure 1: CPI food at home component (bold black), PPI food manufacturing (light blue), and PPI processed meats, poultry and fish (red), all in logs, 2021M01=0. NBER peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray.

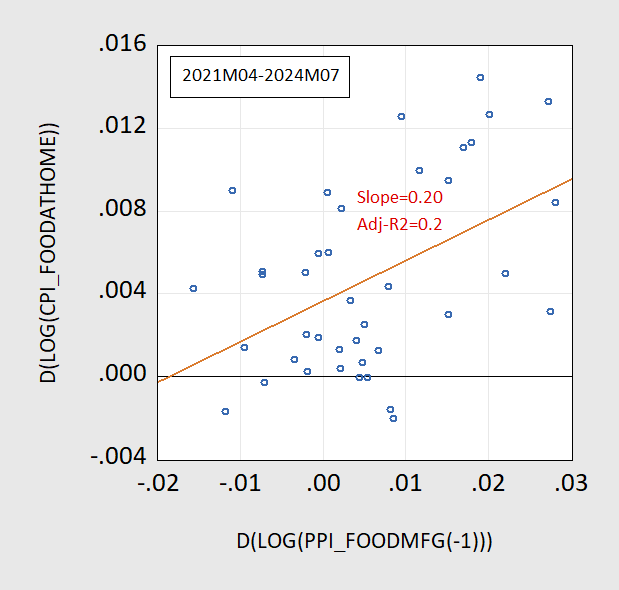

Note that processed meat prices jumped during the pandemic, partly because of the jump in wages (due in part to the pandemic induced constraints in labor supply). See how wages in food processing jumped as foreign born labor supply fell, here. Did the higher manufactured food prices “cause” the higher grocery prices? That’s a complicated question to answer. What one can say is that from the period a year after the NBER-defined trough, to 2024M07, a Granger causality test rejects the null hypothesis that changes in manufactured food prices don’t affect changes in the food-at-home component of the CPI at the 1% msl. The reverse fails to reject, at the 5% msl. Here’s a scatterplot of log first differences of CPI-food at home on lagged PPI-food mfg:

Figure 2: First log differences of CPI-food at home vs lagged PPI food mfg, and regression line.

Now, is the increasingly concentrated nature of the food processing at fault? As MacDonald, Dong and Fuglie, (2023) point out, it’s not clear, at least in the pre-pandemic period.

From the paper (p.36):

Meat and poultry processing industries were transformed as packers built large plants to achieve economies of scale. Processors also formed tighter linkages with a reorganized livestock production sector to assure a dependable supply of livestock to keep plants at near-full capacity. Those transformations led to striking increases in concentration, particularly in slow-growing pork and beef industries, while also leading to lower costs in livestock production and slaughter. However, while there were some significant mergers among processors, much of the growth in concentration came about from the construction of new, or the expansion of, existing plants by the large processors, rather than from mergers among rivals. Despite high levels of concentration, studies of cattle market pricing prior to 2010 found limited evidence of packer market power. Lower processing costs appeared to be largely passed to consumers, and the resulting increased demand for beef in turn led to higher cattle demand and prices. There have been fewer studies of poultry or pork markets, but those studies found only small or local effects from concentration on prices in those industries. However, developments since 2010, which show rising spreads between processor prices paid for livestock and received for meat, as well as new entrants to the industry, suggest that meatpackers now have been able to exercise greater market power over livestock prices than in earlier decades. New entry, and plant expansion among incumbent producers, will determine whether such market power can be maintained.

The offsetting effects from exploiting greater economies of scale vs. greater price power could lead to small increases or even net decreases in output prices. However, the imposition of tightly binding constraints from limited labor supply could change that balance.

Anti-trust actions are much less likely to have distortionary effects on food markets than outright price controls. In any case, it’s unclear to me that outright price controls are what the Harris-Walz campaign has in mind.