(RNS) — Growing up in Philadelphia in a typical American family, “I just really wasn’t from a place that prioritized introspection and nor did I,” said Amelia, who, posting as “sotce,” has become a social media guru offering Buddhist meditation and philosophy through artistic, oddly, or perhaps spiritually, aloof videos and memes.

Amelia, 23, conceals her last name because she says she doesn’t want to distract her audience from her message. “Sort of like a deity,” she said.

In 2021, while studying at a Buddhist monastery in India, Amelia posted her first video on the social media app TikTok. The clip showed a black cat walking along a path in front of a church with natural sound, and overnight it received more than 3 million views.

She continued to post videos demonstrating hand positions, or “mudras,” the Sanskrit word for the gestures that serve in Buddhist art as symbols representing sentiments, such as the expulsion of negativity or the evocation of pure intention. Like clockwork, after posting each clip, Amelia would wake up to millions of views.

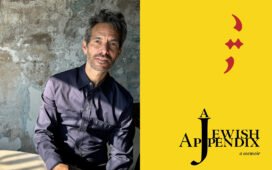

Amelia, an artist and Buddhist influencer who goes by “sotce,” poses in a garden in Manhattan, New York, June 20, 2024. (Photo by Fiona Murphy)

Her audience, as she tells it, fell into her lap. “The algorithm chose me,” she said. “I felt as if the algorithm had selected me to be the one to go viral. Then, I went about it in a way that I thought would bring purification to myself and others.”

After a year in India, Amelia returned to Pennsylvania and launched an account on Patreon, a subscription-based online platform where artists, podcasters, writers and other internet personalities share their work for a monthly fee.

Under the title “the sotce method,” she publishes her writing, answers people’s questions and posts guided meditations. Her accounts on Patreon and Substack, a blogging site, have collectively attracted more than 20,000 paying subscribers. She charges according to a three-tier payment system, with the lowest subscription costing $3 per month and the highest $15. On TikTok, she currently has 424,400 followers, and on Instagram she has nearly 100,000.

The success of her online content has made it possible for Amelia to move into a studio apartment in Manhattan. “I don’t feel worthy of it,” Amelia said. “But no one else is coming. I think my role is necessary. No one else is coming to help.”

By help, she seems to mean the wisdom she dispenses in response to the hundreds of questions she gets sent every day, mostly to women in their late teens and twenties. Her audience asks about topics such as loneliness, how to find happiness and whether they’re too attached to their boyfriend. Some divulge their secrets.

When asked about how to cope with a deep desire for romantic connection, sotce wrote: “We seek our attachments to avoid the present, which would require us to face the groundless meaningless void that is our lives. It’s tragic and also funny … try not to be too hard on yourself.”

Amelia, a follower of Vajrayana Buddhism, or tantric Buddhism, which developed in India and was later adopted by the Tibetans around the 7th century, often cites Buddhist texts in her answers. A core tenet of Vajrayana is a relationship between a student and a teacher on the path to enlightenment. Her comment section features statements such as “sotce is my religion” and “ur our generation’s guru.”

A TikTok post by Venerable Tri Dao. (Video screen grab)

Amelia, an attractive, thin white woman, isn’t the first person to try to build a Buddhism-centered platform online, and there are of course other resources available online for those who want to learn about Buddhism. Right now on TikTok, nearly a quarter of a million videos feature the hashtag “buddhism.” Several of the most popular accounts are run by Buddhist monks like Venerable Tri Dao, who posts several videos a day showing the behind-the-scenes of monastic life.

Other creators, such as Meditate with Mal, post how-to videos that explain the process of making wellness products. Mal also posts short meditation guides. Many of these creators are older than sotce, though her account routinely gets more engagement.

Ophélie Couëlle, a 27-year-old French art student, said she started following sotce in 2021. “Her approach to meditation is super interesting and innovative,” Couëlle said. “I like how she expresses her truth and metaphors of Buddhism.” Couëlle doesn’t consider herself a Buddhist, but often watches meditation videos online.

Blair Seidman, a woman from Florida in her 20s, said, “What resonates with me about sotce’s work is the way that she is able to meet you in those intense profound places that we often find ourselves in alone.” Seidman described sotce as “our creative guide,” adding that the creator is “refreshingly just as vulnerable as we are on the journey.”

Seidman doesn’t consider herself Buddhist or religious in any sense but said she appreciates the religious perspective sotce brings online: “I think oftentimes they (the audience) look for an expression of my faith,” Amelia said, “for me to sort of hold them up to the light, you know?”

Amelia said she sees her role as one resembling the “bodhisattva” — one dedicated to attaining enlightenment and striving to liberate others in doing the same. “I really love answering the questions,” she said. “I think out of everything I’ve done, that’s what I’m proud of.” When asked what role she thinks sotce has in the life of her audience, Amelia says, “I’m not sure what I am to them, but I take it really seriously.”

“In Vajrayana, the idea is that everybody should take the bodhisattva vow and strive to help other people,” Paul Harrison, co-director of the center for Buddhist studies at Stanford University, said. “It’s a feature of Tibetan Buddhism that is particularly strong.”

Amelia posts on TikTok as “sotce.” (Screen grab)

The growing popularity of online influencers like sotce puts into question the faith of a generation considered to be the least religiously affiliated in America’s history. Buddhism, unlike other organized religions, doesn’t require taking vows or formal conversion. “The sotce method” invites the audience to experiment with mudras, meditation and minimalism, which are inherently Buddhist, but not exclusively.

Amelia never outwardly encourages her audience to adopt Buddhism or to take vows.

Half-jokingly, Amelia’s response to why her work is so popular is simply, “my facial symmetry.” The irony of using social media, a platform often criticized for stoking ego, to encourage spiritual enlightenment isn’t lost on the influencer. She believes, however, in the discernment of her audience. “Meditation makes you a better person,” Amelia said. “A better writer, artist, sister, daughter, partner. It just, in every way, helps your life.”

Recently, Amelia posed for a sponsored ad by the luxury fashion brand Coach. As an influencer, she often receives expensive gifts from wellness and fashion brands, and on Reddit there is a page apparently created to criticize her because of these partnerships. One anonymous user wrote: “I feel like building a brand on being spiritual is misleading and her content has become narcissistic.”

Jason Elias, chairman of the board of Shambhala, a global organization founded by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, is a Buddhist scholar widely credited for bringing Tibetan Buddhism to the West. Elias has been practicing Buddhism for 25 years. “I’ve had teachers within the Shambhala tradition say, ‘of course we want people to understand (Buddhism).’ They need to hear about it, and they need to understand it,” he said. “But we don’t ever want to hook them.” “Hooking” people, explained Elias, who works in advertising, relates to the capitalist notion that someone is incomplete without a certain product.

Despite some schools of thought that argue the dharma, or the knowledge of truth that leads to enlightenment, should always be free, Harrison said Buddhism posits no strict moral standard against being an influencer, even if you profit from it.

“The risk of course is that the guru or the teacher will abuse the trust that’s placed on them,” he said.

Amelia, who says that in five years she’d like to be “further along the path,” acknowleges the criticism online. “I am deeply faithful, and my practice and the expression of my practice are very important to me,” she said. “And I also love beauty and fashion and Prada. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t.”