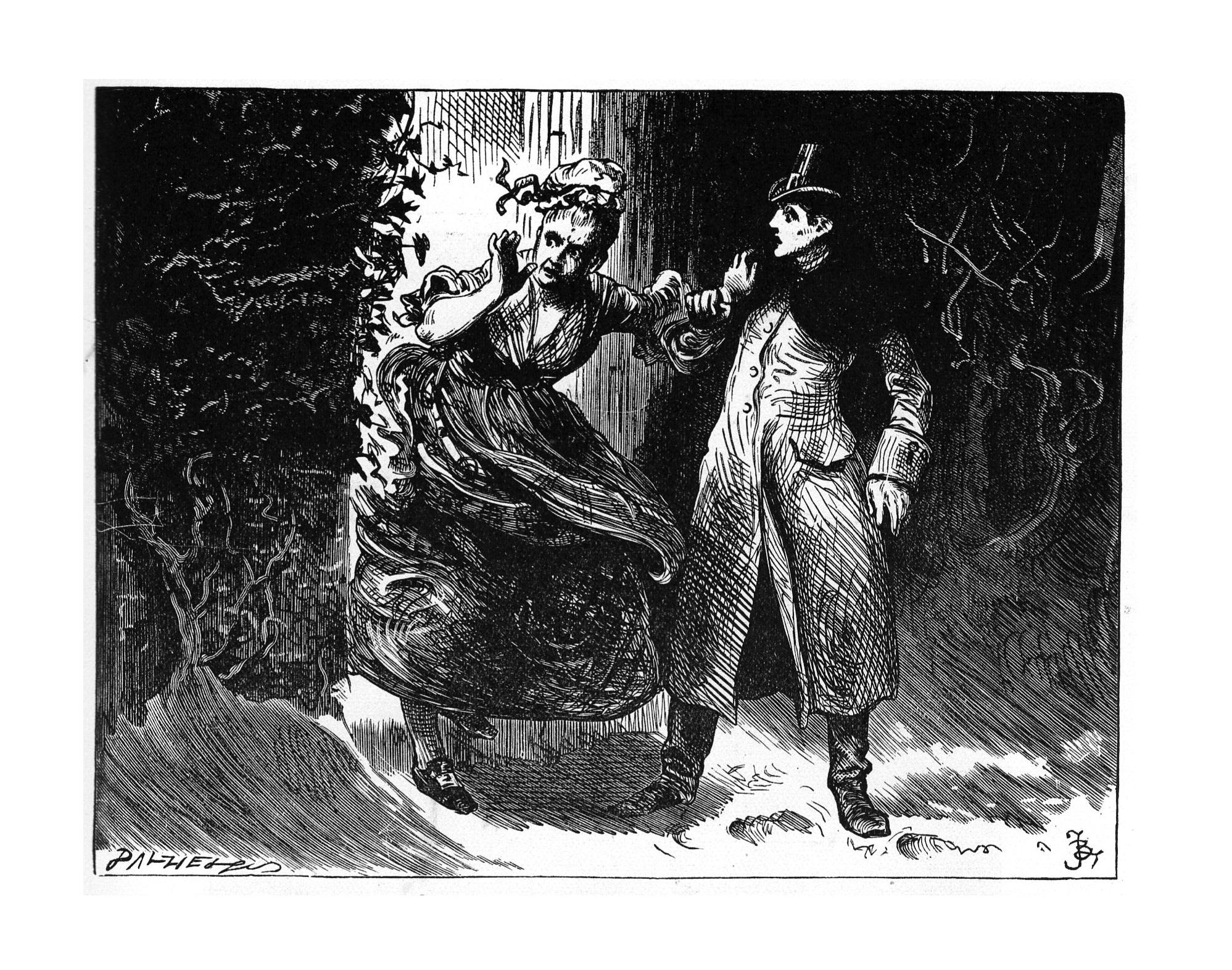

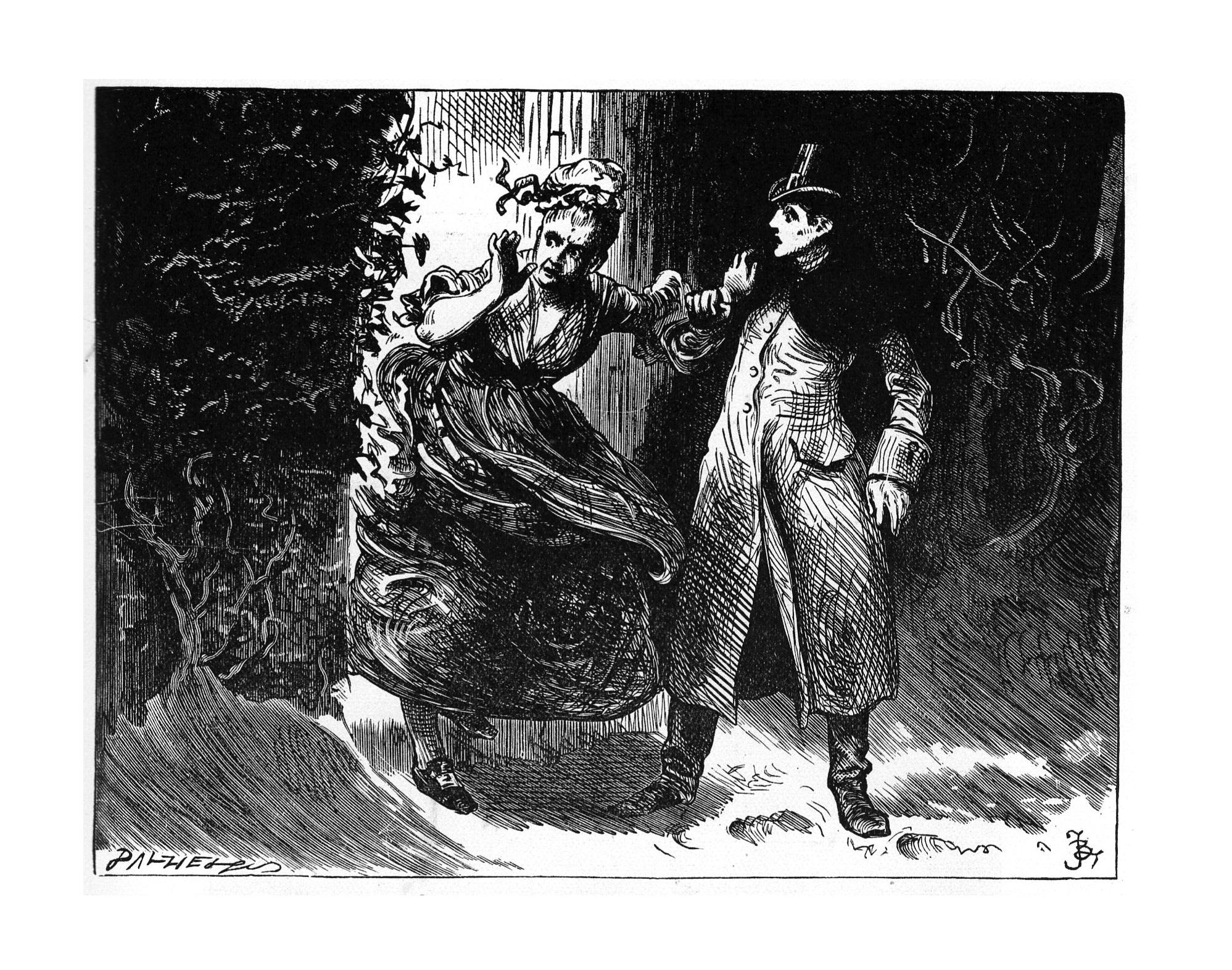

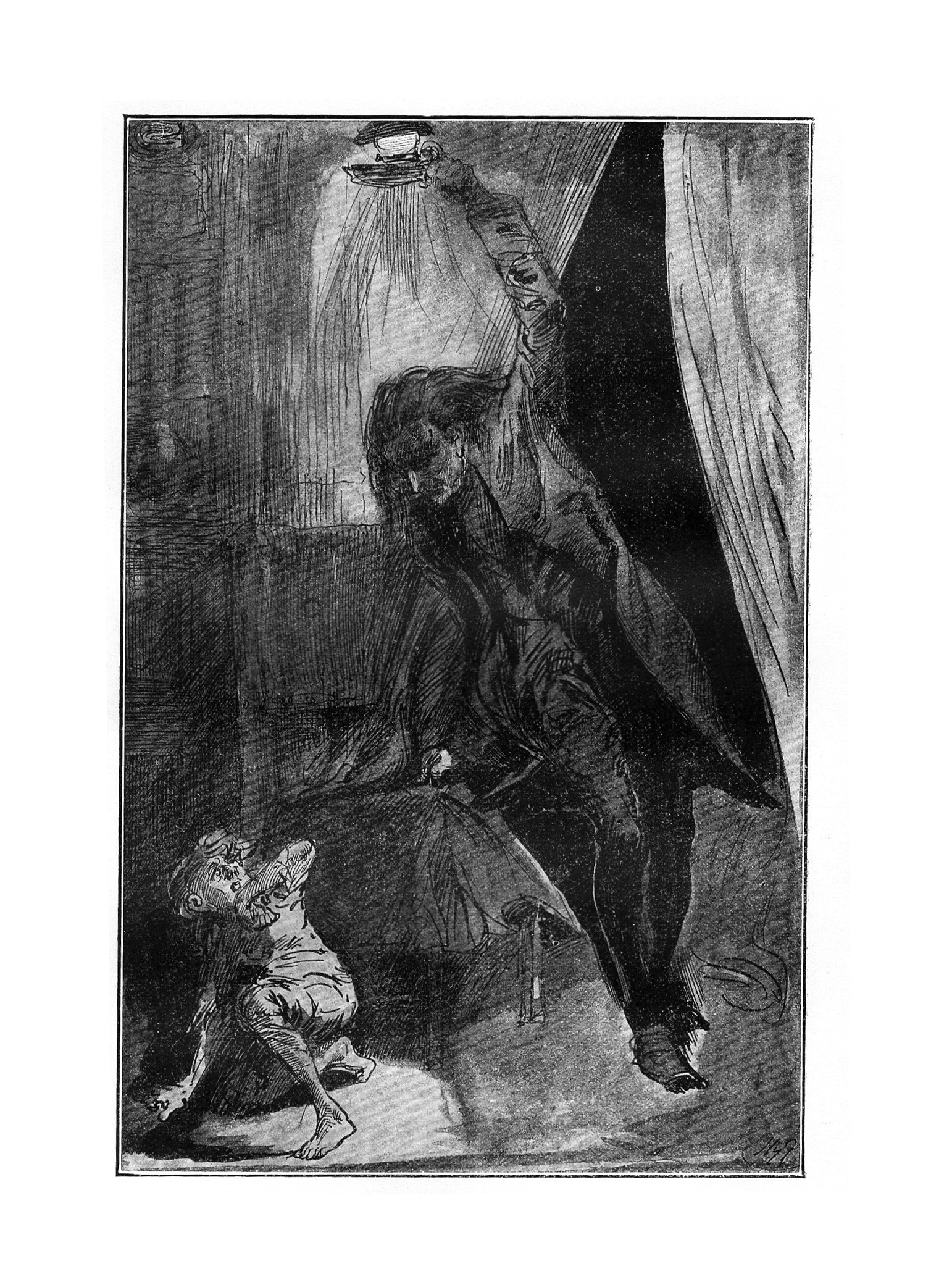

As Christmastime approaches, few novelists come to mind as readily as Charles Dickens. This owes mainly, of course, to A Christmas Carol, and even more so to its many adaptations, most of which draw inspiration from not just its text but also its illustrations. That 1843 novella was just the first of five books he wrote with the holiday as a theme, a series that also includes The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Battle of Life, and The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain. Each “included drawings he worked on with illustrators,” writes BBC News’ Tim Stokes, though “none of them displays quite the iconic merriment of his initial Christmas creation.”

“Anyone looking at the illustrations to the Christmas books after A Christmas Carol and expecting similar images to Mr Fezziwig’s Ball is going to be disappointed,” Stokes quotes independent scholar Dr. Michael John Goodman as saying.

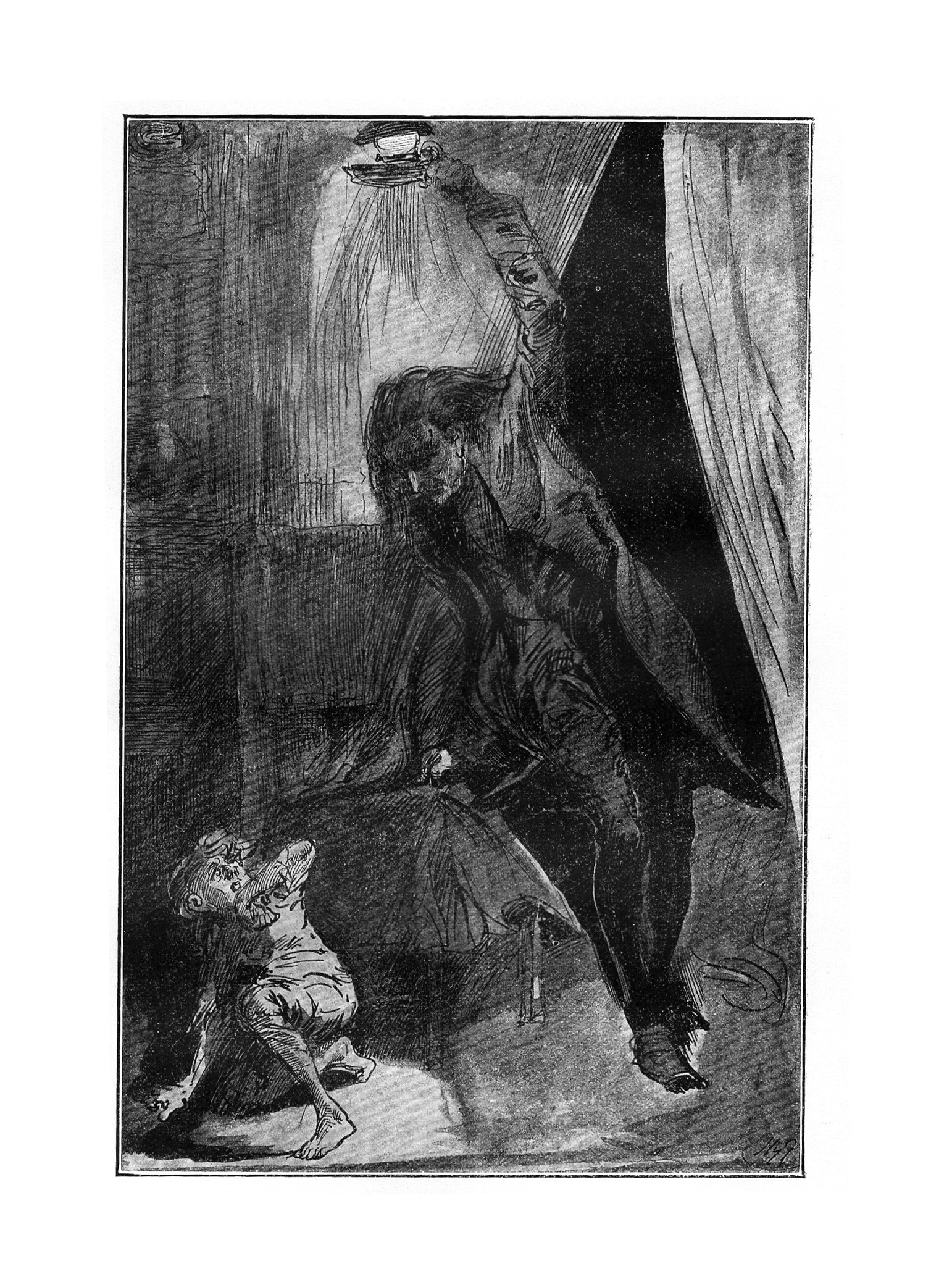

Primarily concerned less with Christmas as a holiday and more “with the spirit of Christmas and its ideals of selflessness and forgiveness, as well as being a voice for the poor and the needy,” Dickens “had to create some very dark scenarios to give this message power and resonance, and these can be seen in the illustrations.”

Goodman’s name may sound familiar to dedicated Open Culture readers, since we’ve previously featured his online Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery, whose digitized art collection has been growing ever since. It now contains over 2,100 illustrations, including not just A Christmas Carol and all its successors, but all of Dickens’ books from his early collection of observational pieces Sketches by Boz to his final, incomplete novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood. And those are just the originals: every true Dickens enthusiast sooner or later gets into the differences between the waves of editions that have been published over the better part of two centuries.

The Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery has entire sections dedicated to the posthumous “Household Edition,” which have even more art than the originals; the later “Library Edition,” from 1910, featuring the work of esteemed and prolific illustrator Harry Furniss; and even the 1912 “Pears Edition” of the Christmas books, put out by the eponymous soap company in celebration of the centenary of Dickens’ birth. But none of them quite matched the lavishness of that first Christmas Carol, on which Dickens had decided to go all out: as Goodman writes, “it would have eight illustrations, four of which would be in color, and it would have gilt edges and colored endpapers.” Alas, this extravagance “left Dickens with very little profit” — and with an unusually pragmatic but nevertheless unforgettable Christmas lesson about keeping costs down. Enter the Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery here.

Related content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.