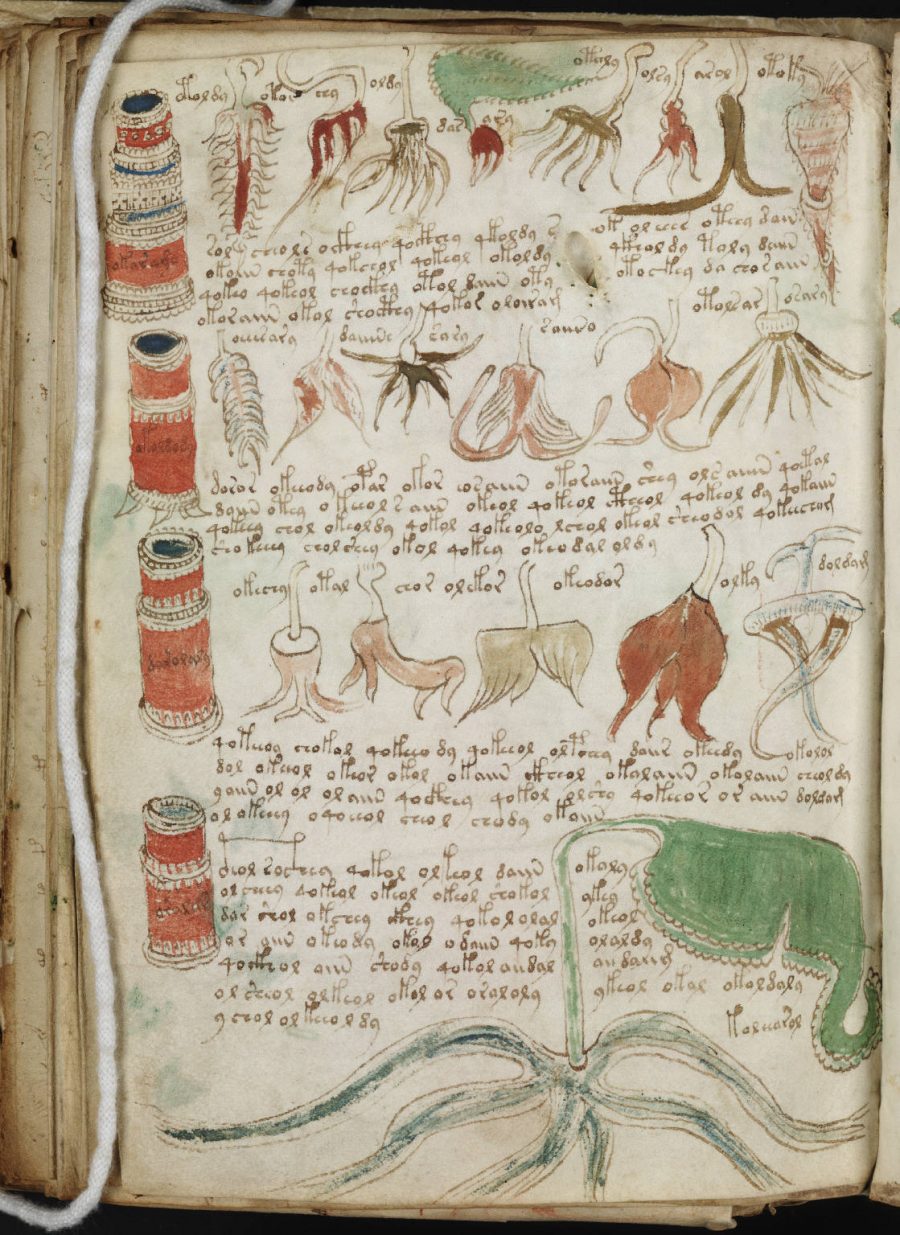

A 600-year-old manuscript—written in a script no one has ever decoded, filled with cryptic illustrations, its origins remaining to this day a mystery…. It’s not as satisfying a plot, say, of a National Treasure or Dan Brown thriller, certainly not as action-packed as pick-your-Indiana Jones…. The Voynich Manuscript, named for the antiquarian who rediscovered it in 1912, has a much more hermetic nature, somewhat like the work of Henry Darger; it presents us with an inscrutably alien world, pieced together from hybridized motifs drawn from its contemporary surroundings.

The Voynich Manuscript is unique for having made up its own alphabet while also seeming to be in conversation with other familiar works of the period, such that it resembles an uncanny doppelganger of many a medieval text.

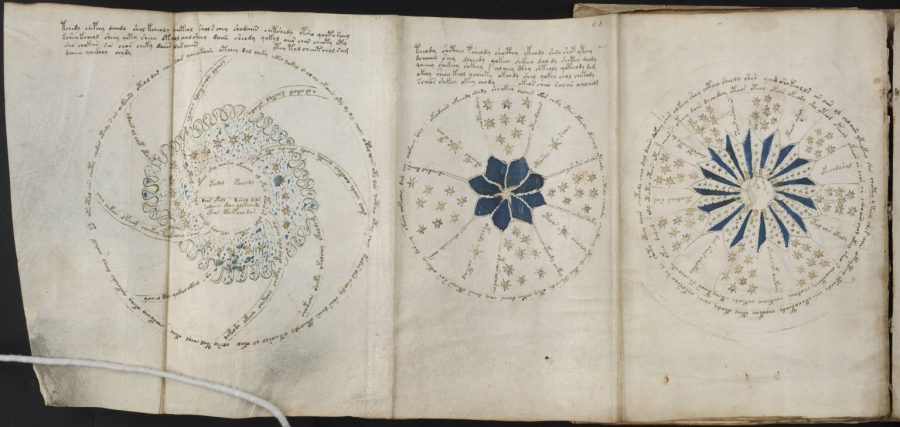

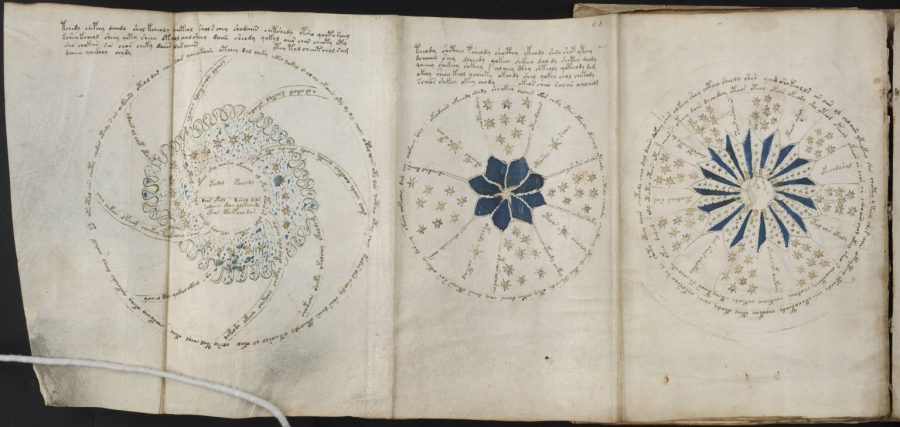

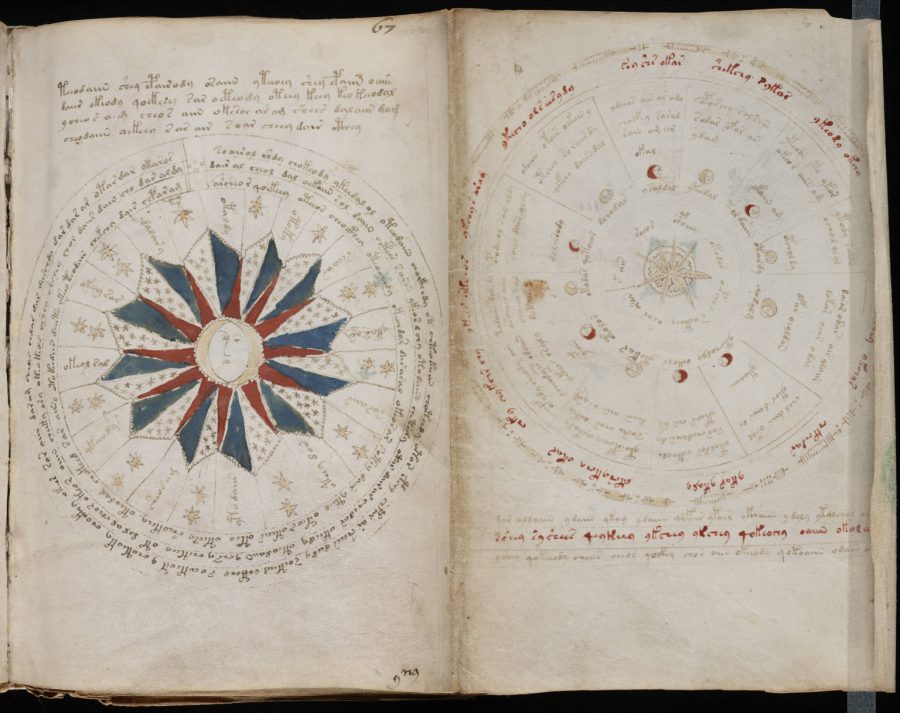

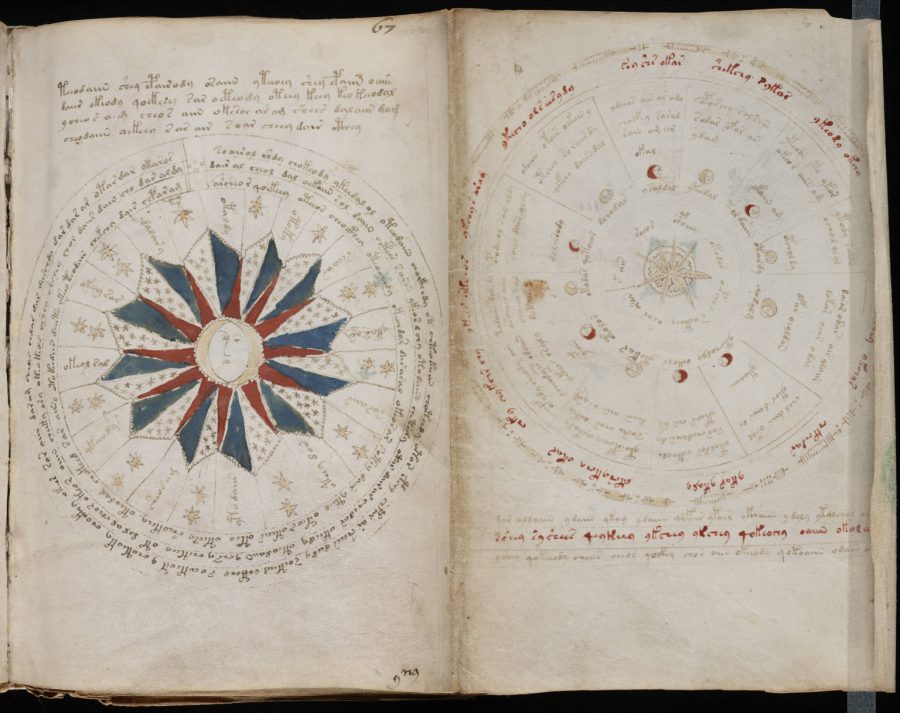

A comparatively long book at 234 pages, it roughly divides into seven sections, any of which might be found on the shelves of your average 1400s European reader—a fairly small and rarefied group. “Over time, Voynich enthusiasts have given each section a conventional name” for its dominant imagery: “botanical, astronomical, cosmological, zodiac, biological, pharmaceutical, and recipes.”

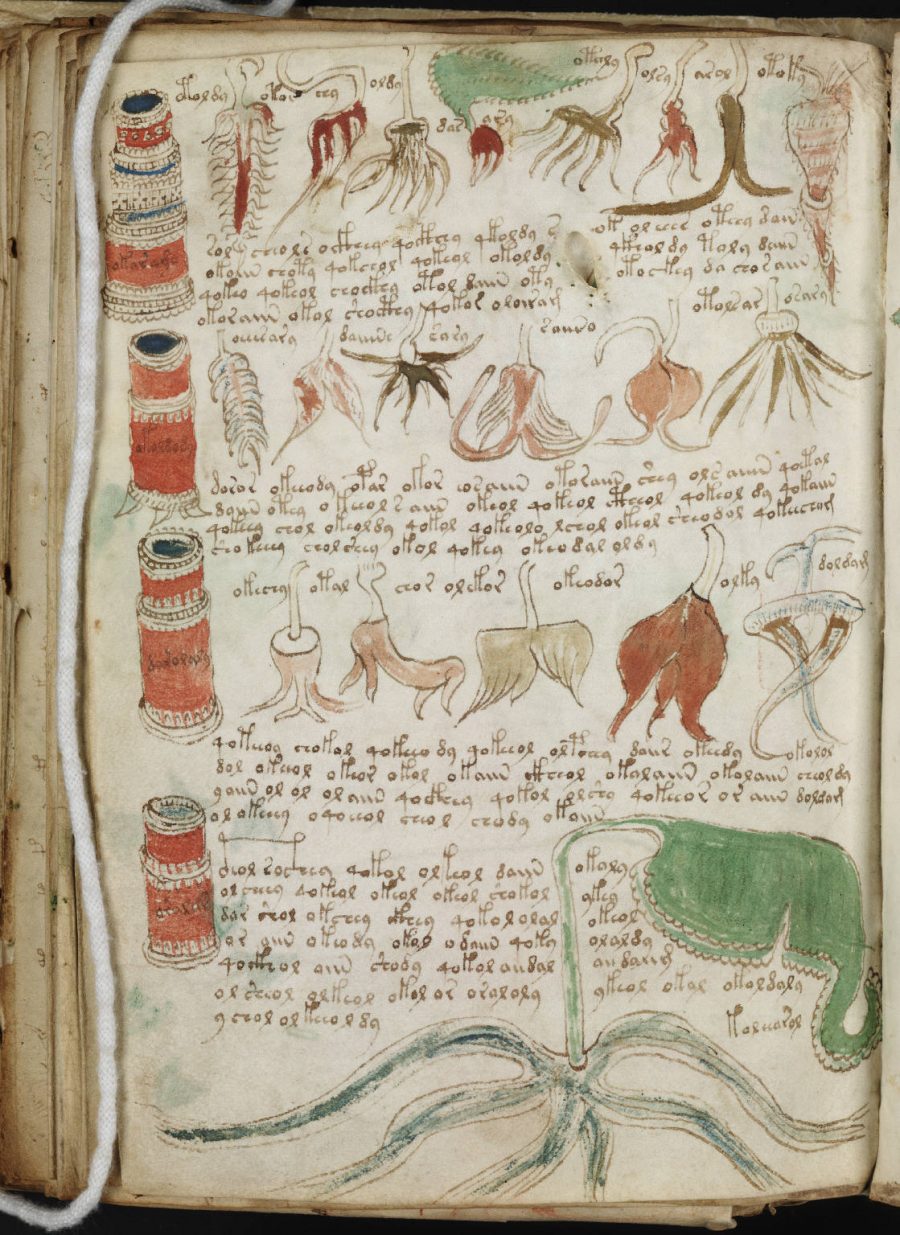

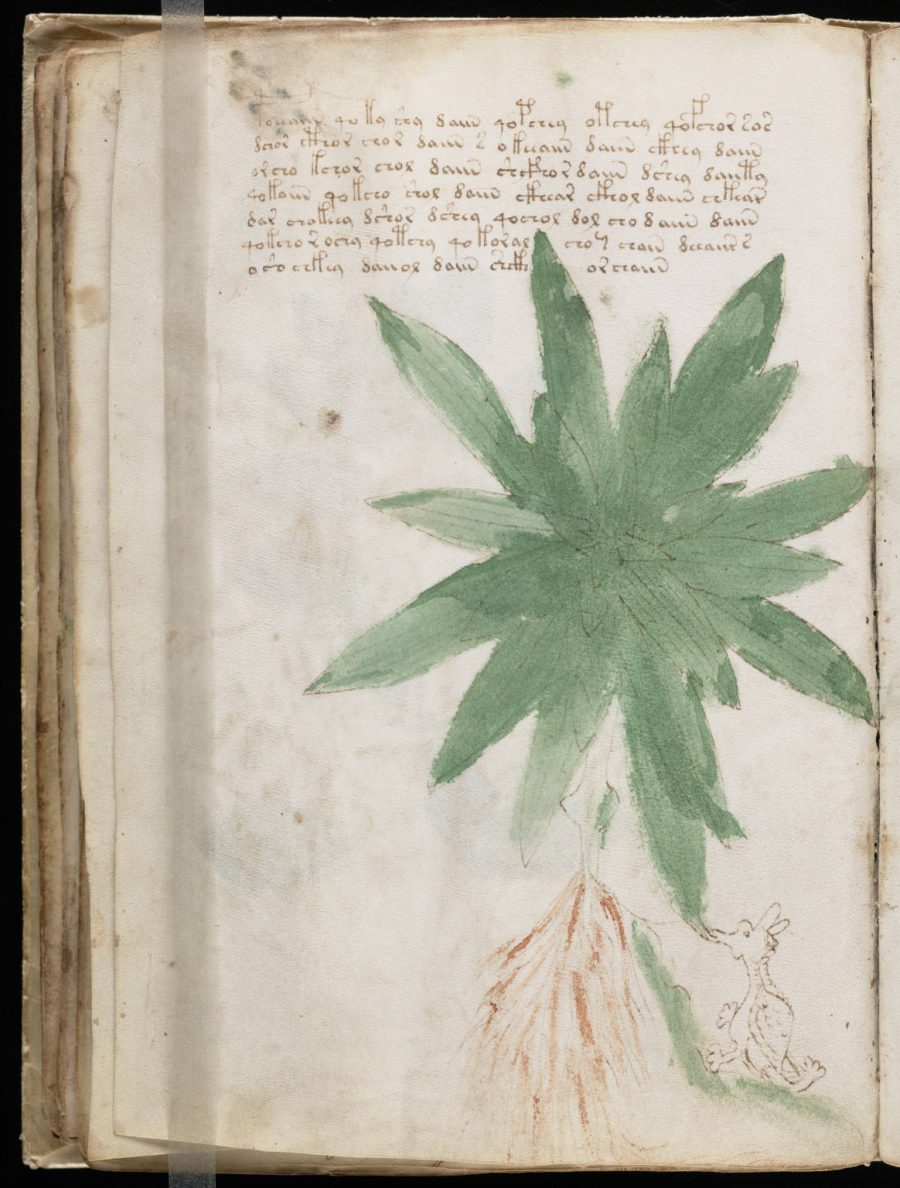

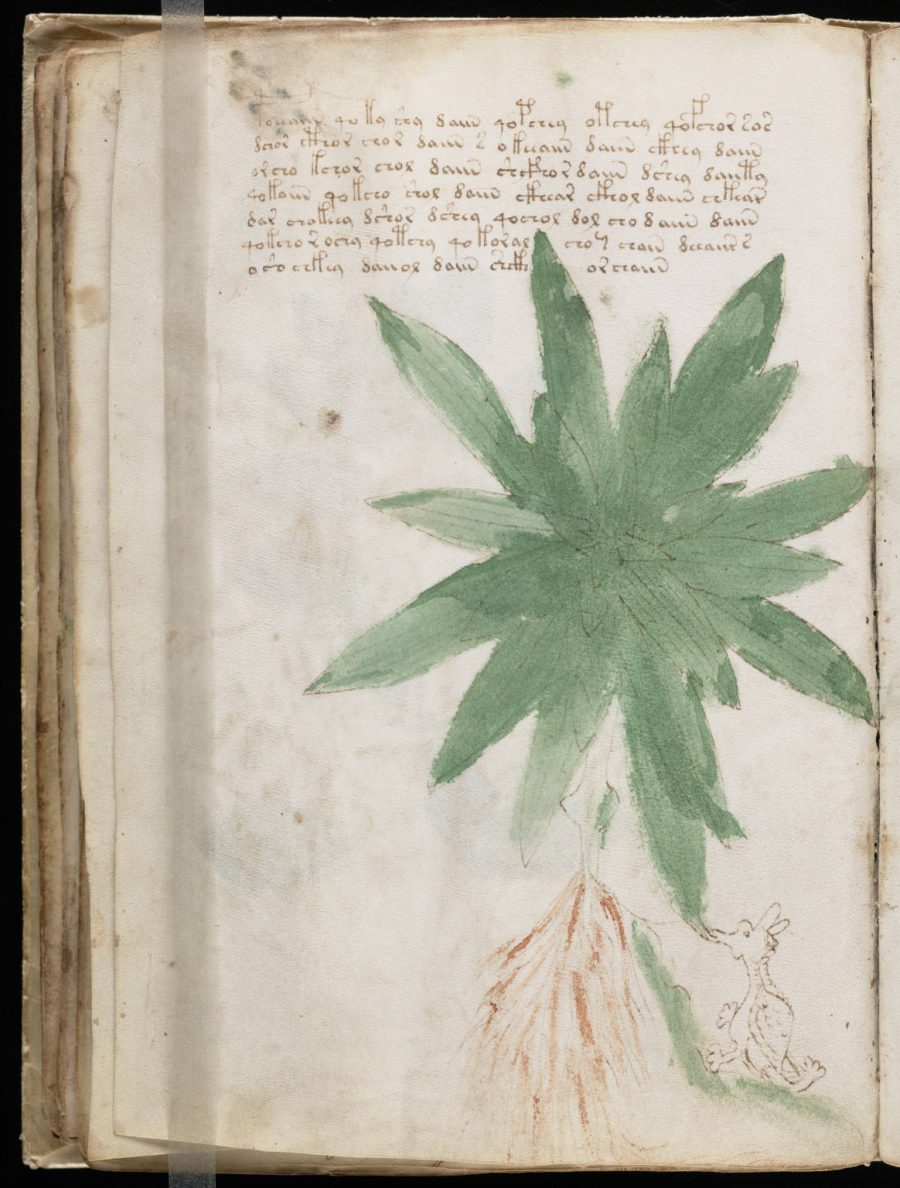

Scholars can only speculate about these categories. The manuscript’s origins and intent have baffled cryptologists since at least the 17th century, when, notes Vox, “an alchemist described it as ‘a certain riddle of the Sphinx.’” We can presume, “judging by its illustrations,” writes Reed Johnson at The New Yorker, that Voynich is “a compendium of knowledge related to the natural world.” But its “illustrations range from the fanciful (legions of heavy-headed flowers that bear no relation to any earthly variety) to the bizarre (naked and possibly pregnant women, frolicking in what look like amusement-park waterslides from the fifteenth century).”

The manuscript’s “botanical drawings are no less strange: the plants appear to be chimerical, combining incompatible parts from different species, even different kingdoms.” These drawings led scholar Nicholas Gibbs to compare it to the Trotula, a Medieval compilation that “specializes in the diseases and complaints of women,” as he wrote in a Times Literary Supplement article. It turns out, according to several Medieval manuscript experts who have studied the Voynich, that Gibbs’ proposed decoding may not actually solve the puzzle.

The degree of doubt should be enough to keep us in suspense, and therein lies the Voynich Manuscript’s enduring appeal—it is a black box, about which we might always ask, as Sarah Zhang does, “What could be so scandalous, so dangerous, or so important to be written in such an uncrackable cipher?” Wilfred Voynich himself asked the same question in 1912, believing the manuscript to be “a work of exceptional importance… the text must be unraveled and the history of the manuscript must be traced.” Though “not an especially glamorous physical object,” Zhang observes, it has nonetheless taken on the aura of a powerful occult charm.

But maybe it’s complete gibberish, a high-concept practical joke concocted by 15th century scribes to troll us in the future, knowing we’d fill in the space of not-knowing with the most fantastically strange speculations. This is a proposition Stephen Bax, another contender for a Voynich solution, finds hardly credible. “Why on earth would anyone waste their time creating a hoax of this kind?,” he asks. Maybe it’s a relic from an insular community of magicians who left no other trace of themselves. Surely in the last 300 years every possible theory has been suggested, discarded, then picked up again.

Should you care to take a crack at sleuthing out the Voynich mystery—or just to browse through it for curiosity’s sake—you can find the manuscript scanned at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which houses the vellum original. Or flip through the Internet Archive’s digital version above. Another privately-run site contains a history and description of the manuscript and annotations on the illustrations and the script, along with several possible transcriptions of its symbols proposed by scholars. Good luck!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

An Introduction to the Codex Seraphinianus, the Strangest Book Ever Published

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness