Yvew here. On one level, it should not come a surprise that individuals cling to pre-existing beliefs on politicized topics like climate change even when facts pile up against them. This propensity has been well demonstrated in the social psychology literature, even if those findings have not gone mainstream.

For instance, one study many years ago demonstrated that when people are presented with contradictory evidence, most instead double down. In the period when even the US press had started retreating from the WMD in Iraq fabrication, a researcher gathered a group of still-true believers. He showed them a video of demonstrating why the claim was false, including, critically, a clip of President Bush admitting as much.

Even with the seeming showstopper of the Bush walk-back from his Administration’s once-dogged assertions, the viewers afterward scored as more, not less, convinced of the validity of the WMD in Iraq story.

Nevertheless, the notion that some who have actually suffered a climate change related disaster would go deeper into denial seems extreme. But this well-done study also includes the role of partisan media coverage around these event in help the doubters find backing for their views.

By Milena Djourelova, Ruben Durante, Elliot Motte, and Eleonora Patacchini. Originally published at VoxEU

As climate-related disasters become increasingly frequent and destructive, one might expect first-hand experience of these events to bring consensus on the urgency of addressing climate change. Yet, the deep ideological divide on this issue in the US and beyond – combined with highly polarised media coverage – may hinder this process. Combining data on the timing and location of US-based natural disasters with large-scale electoral surveys, this column shows that experiencing disasters actually deepens partisan divisions in climate change attitudes, with significant implications for the public debate and policymaking.

The question of how to increase public support for climate action is at the forefront of policy debates in many countries and is becoming increasingly urgent (Dechezleprêtre et al. 2022, Furceri et al. 2021, Douenne and Fabre 2022).

Yet, partisan differences in public perceptions about the existence and importance of climate change have been increasing over the past decades. For instance, in 2001, 48% of Republicans and 61% of Democrats in the US believed that the effects of climate change had already begun. Today, only 29% of Republicans share this belief, compared to 82% of Democrats (Saad 2021). These diverging trends are concerning, as they suggest that finding common ground on climate solutions may become increasingly difficult in the future.

At the same time, the frequency and severity of climate disasters have been increasing over time (International Panel on Climate Change 2014). Numerous studies have explored the relationship between disaster experience and views on climate change or environmental behaviours; yet, the evidence remains mixed. Some studies find a significant positive impact (Hazlett and Mildenberger 2020, Deryugina 2013, Baccini and Leemann 2020), others a mixed or qualitatively small positive impact (Konisky et al. 2016, Bergquist and Warshaw 2019), and yet others find no effect (Marquart-Pyatt et al. 2014, Carmichael et al. 2017).

In a recent paper (Djourelova et al. 2024a), we revisit the evidence by examining how individual beliefs about climate change respond to disaster experiences in the short term, with a particular focus on ideology as a lens through which these experiences are filtered.

Ideological Differences in the Attribution of Disasters to Climate Change

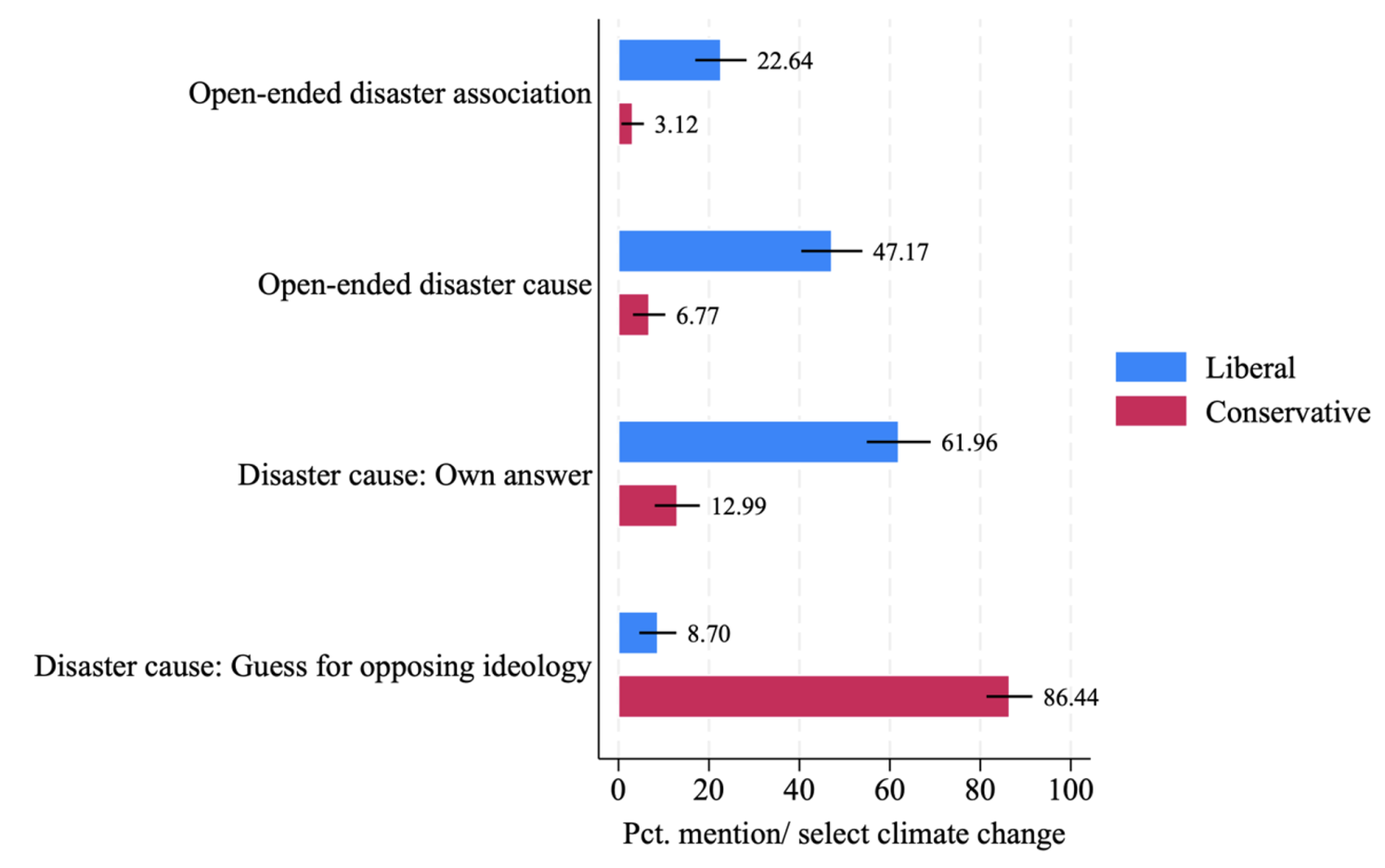

Our analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we conduct online surveys to understand how individuals reason about the causes of disasters and their association with climate change, using Hurricane Ian as a salient case study. Our findings suggest vast ideological differences in the attribution of the hurricane to climate change and, respectively, in the willingness to support climate action (Figure 1). This suggests that the occurrence of the same disaster is interpreted very differently depending on individual ideology. Eliciting second-order beliefs, we also find that individuals are very much aware of these partisan cleavages.

Figure 1 Attribution of disasters to climate change: Prolific survey

Ideological Differences in the Effect of Disaster Experience on Climate Change Beliefs

In the second and main part of our analysis, we study how individual beliefs on climate change evolve after exposure to a natural disaster. We do so by linking observational data on individual-level views on climate change, expressed in a large electoral survey (the Cooperative Election Study), to the exact timing and location of disasters declared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Our empirical strategy leverages variation in the occurrence of natural disasters in time and space relative to the survey’s roll-out. More specifically, we compare the attitudes of respondents surveyed in the four weeks after a local disaster to those surveyed in the four weeks before the event. We isolate the effect of disasters from other factors affecting climate change attitudes, such as geographical, temporal, or socio-demographic determinants, by comparing respondents living in the same county, who are interviewed during the same year and who share similar characteristics. In order to examine how polarisation on the issue evolves following a disaster, we allow for the effects of disaster exposure on climate change beliefs to differ based on respondents’ political ideology.

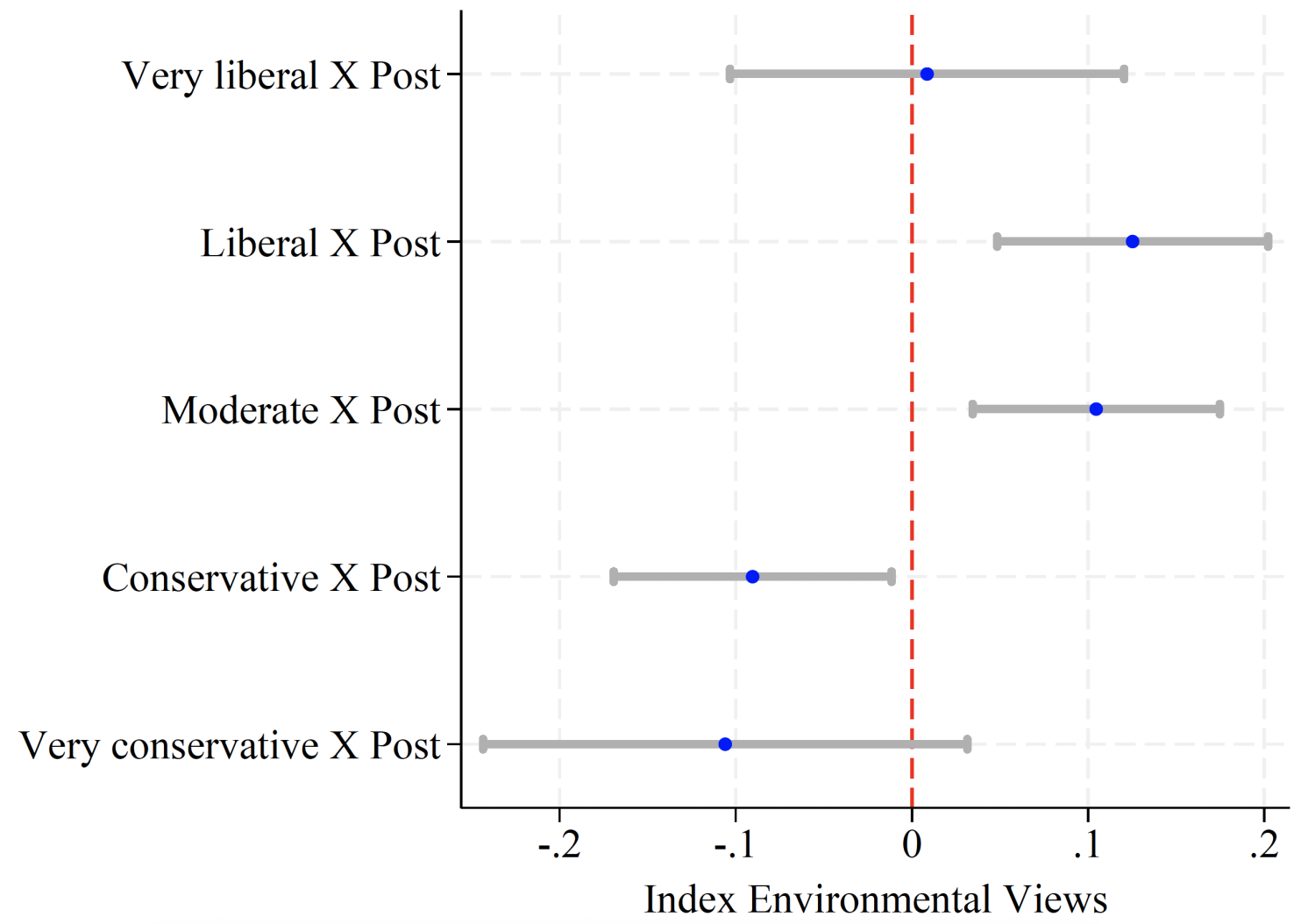

Our findings are striking. We observe that disaster exposure tends to widen the ideological gap in climate change beliefs, not close it. After experiencing a disaster, liberal respondents display an increase in their concerns about climate change of around 1.4–2.6 percentage points relative to their pre-disaster level. Meanwhile, conservative respondents’ concerns for climate change decrease by 2.5–2.6 percentage points. These changes are meaningful as they represent a widening of the partisan gap by around 11%. We do not find similar divergence in views on policy issues other than climate change and the environment, and are able to rule out differential reactions by socioeconomic characteristics correlated with ideology, such as income or age, as an explanation for this pattern.

Figure 2 Change in climate change beliefs following a local disaster

The Role of Media Narratives

One reason individuals may revert to and strengthen their pre-existing climate change beliefs is exposure to ideologically biased media accounts of disasters. Indeed, the media is a powerful lens through which people interpret complex events, and the way news outlets report on these events can significantly affect public opinion (Djourelova et al. 2024b).

To explore this explanation, we examine how local newspapers cover disasters and climate change and whether this coverage influences individuals’ beliefs. We gather all newspaper articles mentioning keywords related to natural disasters, on one hand, and to climate change, on the other, from around 1,200 local newspapers. We then measure differences in the quantity and tone of coverage dedicated to disasters and to climate change between liberal and conservative outlets around local disaster events.

Our findings reveal stark differences between liberal and conservative outlets, both in the quantity and in the tone of coverage. Whilst the volume of climate change coverage produced by liberal outlets increases following a local disaster, conservative outlets do not cover climate change more. This is despite liberal and conservative outlets increasing disaster-related coverage at a similar rate.

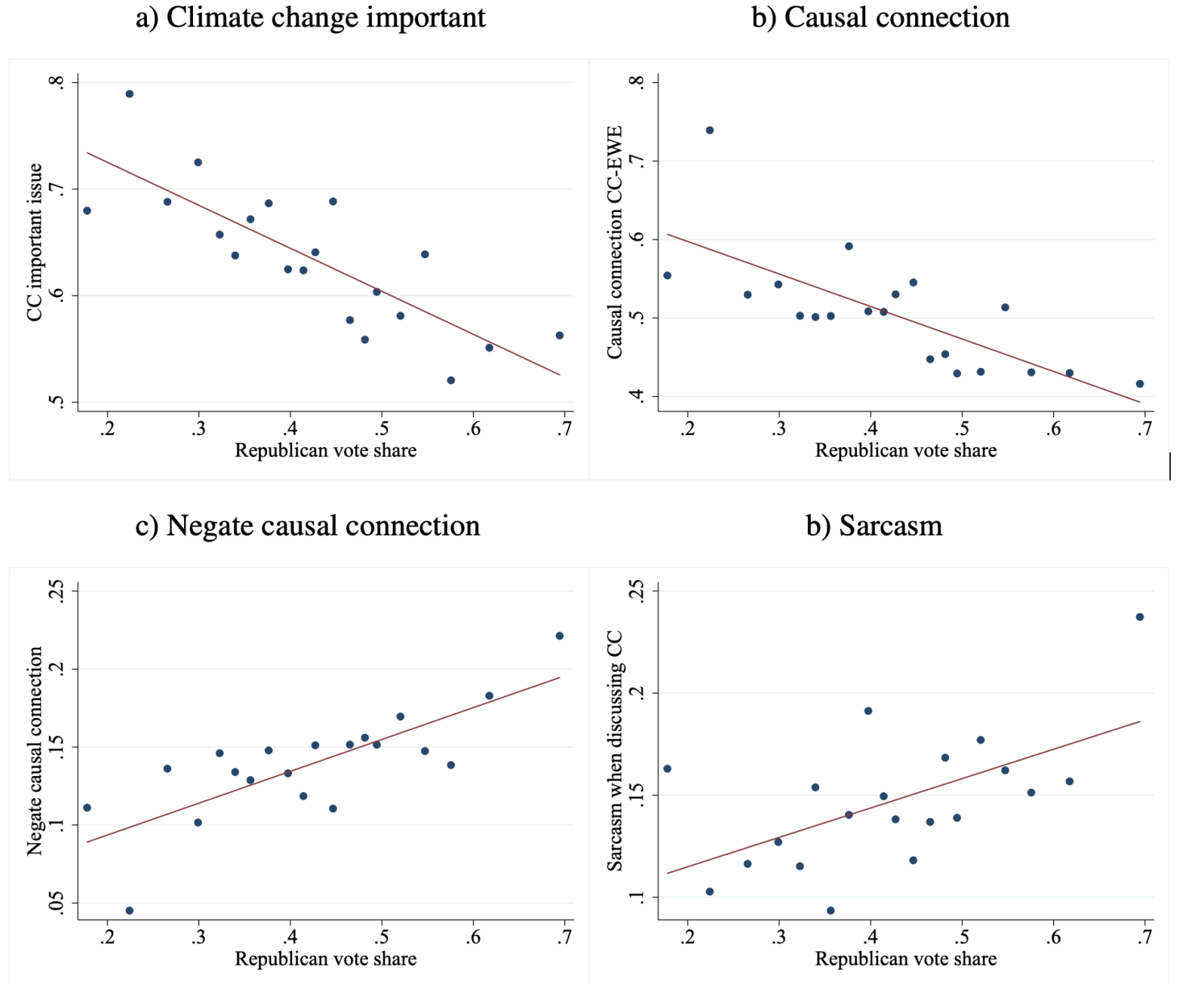

Additionally, we used the new capabilities provided by large language models such as GPT to capture subtle variations in the tone and content of news stories jointly related to climate change and disasters. Figure 3 shows that liberal outlets are more likely to suggest a causal connection between climate change and disasters. They also imply that climate change is an important issue more often than conservative outlets. Conversely, conservative newspapers have a higher tendency to actively negate the causal connection between climate change and disasters and to use sarcasm when discussing climate change. Our analysis shows that these ideological differences in tone are further amplified in the wake of disasters.

Figure 3 Partisan content differences in articles about climate change and disasters

Finally, our analysis suggests that these ideologically biased media narratives may play a role in polarising climate beliefs. Two pieces of evidence point in this direction. First, we find that the polarising effect of disasters is present only in counties with an active local newspaper, where residents are more likely to encounter ideologically framed climate stories. Second, the effect is more pronounced when local media coverage on climate change clashes with respondents’ ideology. For example, conservative individuals residing in areas with high climate-change coverage display the strongest decrease in climate-change concerns after a disaster. Conversely, liberals in areas with limited climate coverage strengthen their environmental concerns more.

Taken together, these findings underline a concerning trend: rather than fostering a united response to climate change, natural disasters may deepen ideological divides, especially when conflicting media narratives reinforce pre-existing beliefs. Our findings have implications for policymakers and activists. First, they suggest that the timing of attempts to raise awareness about climate change matters – as such, efforts may trigger conservative backlash in the immediate aftermath of disasters. Second, they demonstrate that the politicisation of climate change and conflicting messaging in the mass media is a major obstacle to achieving consensus on this matter.

See original post for references