While the world clamoured for him, Farida and her daughters Naayab and Reva remained in Pankaj’s world. A world that turned silent with his passing away at 72 on 26 February 2024. His presence, however, is palpable in his stately bungalow at Carmichael Road. In the larger-than-life frame that adorns the foyer. In the lamp that glows beside it relentlessly. In Farida Udhas’ eyes that light up with love just as they well up with lament. “Pankaj liked me in coloured clothes. He hated it when I wore white, even if it was for a funeral. But now I don’t want to wear colours. I just can’t,” sighs the lady in white as she relives her life and times with the legendary singer. In Farida Udhas’ own words:

Friends for Life

I first met Pankaj at his neighbour’s house on Warden Road in 1979. He was beginning his career in those days while I was flying with Air India. My first impression of him was of a kind and gentle person, something that remained unaltered. Initially, we were just friends – we enjoyed playing cards, spending time together, and going out occasionally. Gradually, our friendship deepened. It was never about gifts or material things for me. What I valued most was Pankaj’s simplicity. Yes, I did borrow money to help Pankaj release his first album, Aahat (1980). It was a small gesture on my part. I understood his worth and the struggle he was going through. Luckily, the album took off and he never looked back. Aahat was followed by Mukarar, Tarrannum, Mehfil, Pankaj Udhas Live at Royal Albert Hall in 1984, Nayaab, and Aafreen among others.

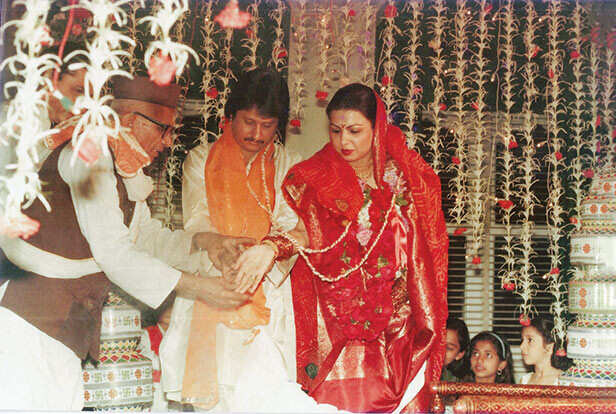

Marriage Matters

Ours was a three-year courtship, which culminated in marriage on 11 February 1982. My aunt was instrumental in getting us married. She told my father, an ex-police officer, that we were meant to be (Pankaj was a Hindu and I a Parsi). Pankaj had charisma. My father, as strict as he was, was charmed by him and loved him like a son. Pankaj gave him as much respect and love. Eventually, Dad gave his licensed gun to Pankaj. At first, Pankaj and I rented a place in Bandra. We moved here to Carmichael Road in 1986. Our first daughter, Nayaab, was born the same year. He named his album Nayaab (which includes the famous Ek taraf usska ghar) after her. Reva was born in 1995. Marriage entails give and take. When Pankaj began travelling for shows, I gave up my job to be around the kids. He relied on me for everything. Initially, I was short-tempered. But gradually, I changed for the better. Through time we remained best friends. We understood each other; we could have honest conversations and tell each other where we were going wrong. There was tremendous faith and trust between us. If a female reporter came to interview him while on his tours, he’d never call her to his room. He’d go down to the lobby for the meeting; such was his respect for them.

Religion of Love

We respected each other’s religions. My prayer room venerates every deity. If on certain days I couldn’t light the diya, Pankaj would do it and recite the Parsi prayer just as he did the Hanuman Chalisa every day. We held a Satyanarayana Katha on Dussera and poojas at our office and studio during Diwali. I fasted during Navratri. We’d drive down to Pankaj’s ancestral home in Gujarat to pay our respects during Navratri. I visit the fire temple, dargahs, churches and mandirs. God is one. How you worship Him doesn’t matter! I want to be cremated like Pankaj. I want my loved ones to be present during my last rites. In fact, I’d shared this sentiment with Pankaj as well. But sadly, he went before me.

Art and Heart

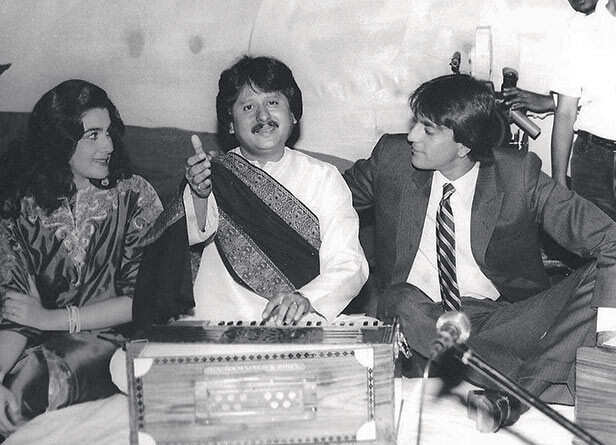

Pankaj did riyaz every day, which ensured the smoothness in his voice. Pankaj learnt Hindustani vocal classical music from Ghulam Qadir Khan Sahab and trained under Navrang Nagpurkar from the Gwalior Gharana in Mumbai. He never copied anyone. He had his own individuality. He simplified ghazals for the masses. He learnt Urdu from a Maulvi and perfected his diction. His commitment towards the genre was immense. He’d be upset when his ghazals were alleged to be only about sharab (wine). They were not about intoxication but were metaphors of love and life. He encouraged new poets including Mumtaz Rasheed (Jheel mein chaand nazar aaye), Sheikh Adam Abuwala (Chand chamka hai chandni ke liye), Nasir Kazmi (Dil dhadakne ka sabab), Zafar Gorakhpuri (Aur ahista kijiye baatein), Saeed Rahi (Yeh hai fasana), S. Rakesh (Thodi thodi piya karo)… along with veterans.

He won fame in film playback with Chitthi aayee hai in Mahesh Bhatt’s Naam (1986), where he played himself. Ironically, for some reason (the film industry was on strike), Filmfare Awards were not

held that year. Or I guess he’d have won it. There’s so much heart in the song. The first time he sang it ‘live’ was at Madison Square Garden in New York. People were sobbing, crying. The song evokes so much yearning, so much nostalgia amongst Indians across the world. He couldn’t end any show without Chitthi aayee hai. Later, Pankaj, playing himself, rendered ghazals Jeeye toh jeeye kaise in Saajan (1991), Kisine bhi toh na dekha in Dil Aashna Hai (1992) and Dil deta hai ro ro duhai in Phir Teri Kahani Yaad Aayi (1993) among others.

Usually, you associate hysteria with pop artistes. But the frenzy for his genre, the ghazal, was unique. Last year, he held a private show in Benares with about 2000-3000 people. There were at least 600 people waiting outside the hall. There were ‘old faithfuls’ who’d always make it for his shows. Like a mother-daughter duo, who attended all his concerts at Nehru Centre in Worli. Or the devoted fan from Nagdwara, who made it a point to hear him perform live. Pankaj was never rude to his fans. Pankaj would seek honest reviews from the children and me. During the interval, he’d ask us, “Was I okay?” Four months before he passed away, he held a concert at the Royal Opera House in Australia. It was perhaps his most memorable show given the audience’s enthusiasm. Moreover, the sight of his daughters seated in the audience made him sentimental and moved him to tears

End That Isn’t

Pankaj had been suffering from diverticulitis for a couple of years. Until October 2023 he was fine until there began fluid accumulation in the lungs. He was to undergo a procedure at the hospital (Breach Candy Hospital) for it on February 26, 2024. We had dinner together at the hospital the previous night. He watched the film Sholay. Around midnight, the children left for home. At 3.30 am, his pressure suddenly dropped. Reva returned immediately. She left at 7.30 am when his oxygen saturation was better and Nayaab came in. Suddenly, within one and a half hours, things changed. It was all over. No one imagined the end would be so quick. Last year, all four of us visited Benares and cherished the spiritual experience. As a tribute to that, we immersed half of Pankaj’s asthi (ashes) at the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi and the other half in Triveni Sangam near Somnath Temple in his birthplace, Gujarat.

After Pankaj passed away, we received many messages from friends and strangers sharing how Pankaj had touched their lives. During the funeral, a gentleman told Nayaab, “I’ve come to say thank you. When my father came to Mumbai, he had no money. Your father gave him Rs 20,000 every month. I owe everything, my education and my life to Pankajji.” Pankaj was deeply compassionate. Khazana – A Festival of Ghazals (an initiative started by Pankaj, Talat Aziz and Anup Jalota in 2002 in partnership with CPAA – Cancer Patients Aid Association and PATUT – Parents Association Thalassemic Unit Trust) expressed his support for the ailing. Also, the platform gave budding singers a chance to sing with veterans. Hopefully, Nayaab will carry the legacy forward. As for me, it’s difficult to accept life without Pankaj. I don’t believe the intensity of the pain will ever lessen. I just want my daughters to settle in life. The way he loved me makes me miss Pankaj so much. I miss him with every breath. If reborn, I’d wish Pankaj to be my husband yet again.