The Wall Street Journal published a seemingly pretty good piece, Elite Colleges Have a Looming Money Problem. However the funding squeeze has long been in the making and it might have behooved the Journal to call more attention to the management lapses earlier.

Readers are likely broadly familiar with the operating side. We’ll turn to the Journal’s account soon, but the very short version is that college tuitions have risen strongly over time, without an improvement in university economics, due to wild bulking up of the adminisphere, significantly due to the weird perceived need to chase donors to fund a higher cost base that did not translate into improved instruction or more funding of research.

Instead, the improvement was pure Potemkin: glitzier dorms, fancy gyms, so as to create more donor naming opportunities. Pray tell, since when does glamorous housing translate into sharper minds? But one can see from a social engineering standpoint why some may have favored getting students used to living high. They’d be more easily tracked into elite-suitable, well-paying (or deemed as suitable employ by well-paid spousal material), since taking a more modestly paid but arguably more productive-to-the-public post would amount to a lifestyle hit.

The Journal does correctly point out that a a whole series of bad policies and practices are coming home to roost, to the degree that even heftily endowed universities are having to engage in some rethink. However, it seems extremely unlikely that they will engage in desirable and one might argue necessary changes, like returning to their roots as schools of higher learning, rather than hedge funds and real estate investors with education subsidiaries.1

Having lived lavishly for so many years, the top schools are now feeling pinched for (at least) two reasons. First is a falloff in new donations due to unhappiness among Zionist donors over what they deemed to be insufficient crackdowns on university protests over genocide in Gaza and student criticism of Israel’s apartheid. Second is that Trump China/immigrant-bashing has resulted in reduced applications and enrollments of foreign nationals, who were very attractive to these institutions because many paid full fees, effectively subsidizing other students. Even if Trump does not make this situation directly worse by tightening visa rules, a continued strong dollar will exert a dampening effect.

But to those who have been following our work on private equity, CalPERS, and investment management over the years, the cheeky part of the Journal account is depicting underwhelmeing investment performance at university endowment offices, which typically have very well paid in-house teams that then select outside managers, as if that were news. It most assuredly is not.

The story unwittingly signals that it’s really not on top of this topic by making former Harvard president Larry Summers the first expert it cited:

Former Harvard President and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers estimated this year that if Harvard had been able to just keep up with other Ivies and “large endowment schools” in the past several years, it would have $20 billion more. For perspective, he says that just $1 billion could fund 100 professorships or permanently cover tuition for 100 students.

Two paragraphs later:

During the financial crisis, when donations plunged and costs rose, Harvard also faced steep investment losses and collateral calls on derivatives. With some investments hard to sell and money already committed to the university, HMC had to exit some stakes at distressed prices and the university was forced to postpone capital projects and borrow to cover the shortfall.

Today it doesn’t face the same derivatives exposure….

Help me. Summers was the arsonist who burned all that Harvard money! From a 2013 post :

Summers, unduly impressed with his own economic credentials, overruled two successive presidents of Harvard Management Corporation (the in-house fund management operation chock full of well qualified and paid money managers that invest the Harvard endowment). Not content to let the pros have all the fun, Summers insisted on gambling with the university’s operating funds, which are the monies that come in every year (tuition and board payments, government grants, the payments out of the endowment allotted to the annual budget). His risk-taking left the University with over $2 billion in losses and unwind costs and forced wide-spread budget cuts, even down to getting rid of hot breakfasts….

Without overburdening you with detail on the swaps that blew up Summers’ piggy bank (see this Bloomberg story for the particulars) let there be no doubt that Summers signed up to be a chump to Wall Street. As Epicurean Dealmaker remarked when the Bloomberg expose came out (emphasis ours):

Now forward swaps, or forward start swaps—which behave like normal swaps except the offsetting fixed and floating rate payments are scheduled to start at a date certain in the future—by themselves count as little more than rank interest rate speculation, specifically in this instance as a bet that short-term interest rates will rise in the future. They can make a great deal of sense when an issuer intends to sell bonds in the relatively near future and when the issuer wants to hedge against budgetary uncertainty by converting floating rate obligations into fixed rate debt. That being said, I have rarely encountered a corporate client who feels confident enough about both their absolute funding needs and current and impending market conditions to enter into a forward swap starting more than nine months into the future. Entering into a forward start swap for debt you do not intend to issue up to 20 years in the future sounds like either rank hubris or free money for Wall Street swap desks.

The next unintended tell the use of the work of the dean of quant analytics and investment, Richard Ennis, right after the first mention of Summers:

But even Harvard’s peer group isn’t doing as well as it could. Veteran investment consultant Richard Ennis wrote this month that high costs and “outdated perceptions of superiority” have stymied Ivy League endowment returns, which could have been worth 20% more since the 2008 financial crisis if invested in a classic stock and bond mix.

That section makes it sound as if the Ennis finding about endowments having high expenses and as a result, flagging performance was news. It isn’t. Ennis has been publicizing his findings about this for years. See some of our posts on his papers: New Study Slams Public Pension Funds’ Alternative Investments as Drag on Performance and An Indictment of the “Standard Model” for Pension and Endowment Investing in 2020 and Endowments’ Money Management Destroying Value Demonstrates Economic Drain of Asset Management Business in 2021.

Even worse, the Journal does not explain why endowments have become investment laggards. This is the further discussion of Ennis’ work:

Harvard has more than three-quarters of its endowment in private equity, hedge funds or real estate and just 14% in publicly traded stocks. Harvard Management Co. doesn’t break out fees in its reports and a spokesman didn’t provide that information, but Ennis estimates that the all-in cost of management for such assets is easily 3%, which is a gigantic drag.

This does not give any clue as to why costs are out of line. Ennis made the point clear in the an early 2020 paper we highlighted. From our post:

We are embedding an important new study by Richard Ennis, in the authoritative Journal of Portfolio Management…

Ennis’ conclusions are damning. Both the pension funds and the endowments generated negative alpha, meaning their investment programs destroyed value compared to purely passive investing.

Educational endowments did even worse than public pension funds due to their higher commitment level to “alternative” investments like private equity and real estate. Ennis explains that these types of investments merely resulted in “overdiversification.” Since 2009, they have become so highly correlated with stock and bond markets that they have not added value to investment portfolios. From the article:

Alternative investments ceased to be diversifiers in the 2000s and have become a significant drag on institutional fund performance. Public pension funds underperformed passive investment by 1.0% a year over a recent decade; the annual shortfall of endowments is 1.6% a year.

Note that we’ve been telling readers since we started covering private equity regularly, in 2014, that it did not outperform equities on a risk-adjusted basis. The case against private equity has only gotten stronger over the years. Yet investors like CalPERS and Harvard finessed the flagging returns by adjusting benchmarks and in CalPERS’ case lowering the risk premium, without providing a credible justification, from 300 basis points to 150.

The Journal also omits one reason for endowments’ undue enthusiasm for alternatives: to curry favor with, or at least not alienate, big fund managers among its alumni who have been or might become big donors.

Admittedly, these top schools are facing pressure on a new front: being less than fully tax exempt by virtue of those fat endowments. Again from the Journal:

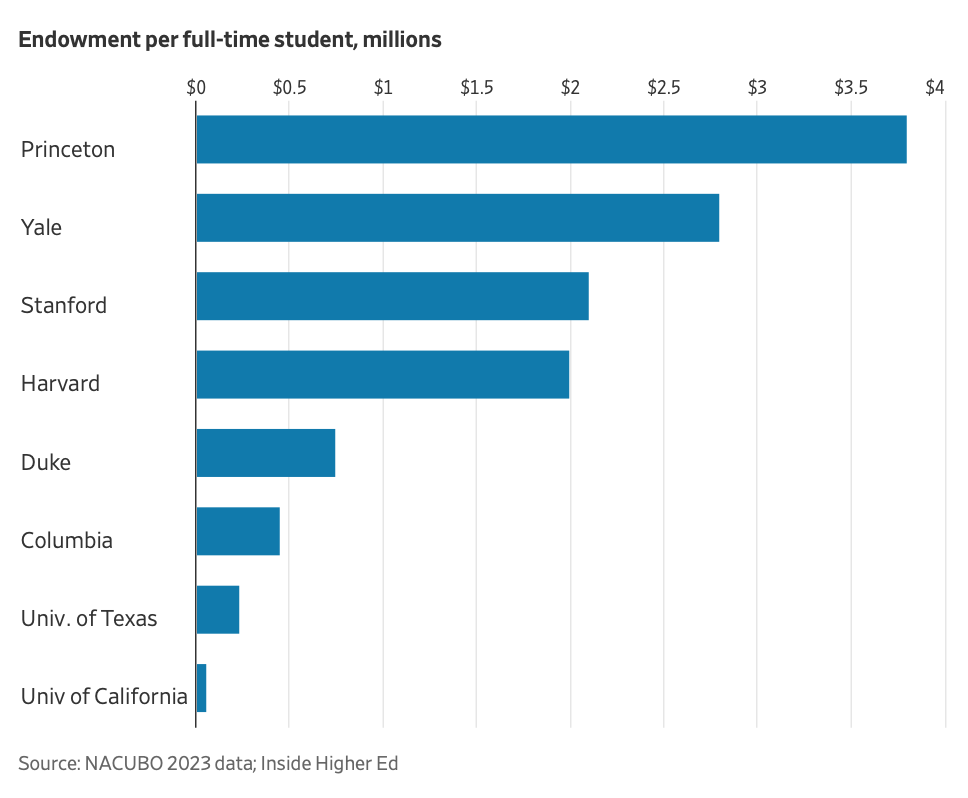

Two Trump administration policies could further weigh on Ivies’ finances. One is a 1.4% tax on income levied as part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on endowments larger than $500,000 per student at schools with more than 500 students. A few dozen schools have had to pay it and there is talk of increasing the levy.

The article concludes that like overvalued stocks, universities have considerable downside risks:

Domestic demographics won’t help. Paul Weinstein Jr. of the Progressive Policy Institute writes that, starting next year, colleges will face an “enrollment cliff” that will see them lose 575,000 students over four years. Yet a booming stock market and competition for student tuition dollars has led to massive growth in university bureaucracies far exceeding tenured staff hires. More than three million people are employed by four-year colleges and Weinstein notes that some actually have more non-faculty employees than students, including Duke and Caltech.

The more elite the college, the less they will suffer from a drop in overall U.S. enrollment…A drop in stocks, or a reckoning that reveals their opaque private-equity funds aren’t as valuable as they look on paper, would leave a mark, though.

Some Journal readers objected to the criticism of Caltech’s level of non-faculty workers, contending that many were working on funded research and thus paying their own way. But they did complain about tenured faculty often being paid $200,000 to $400,000 a year. I find more disturbing the number how earn even more than their uni compensation on outside consulting. This is particularly true for law and business profs at top schools.

The general point remains: smaller, less well endowed schools are already under duress, with some even closing. Even the biggest, fattest institutions look set to feel some pain. The open question seems to be how much.

_____

1 For instance, Columbia University is the third biggest land-owner in New York City, after the city itself and the Catholic Church.