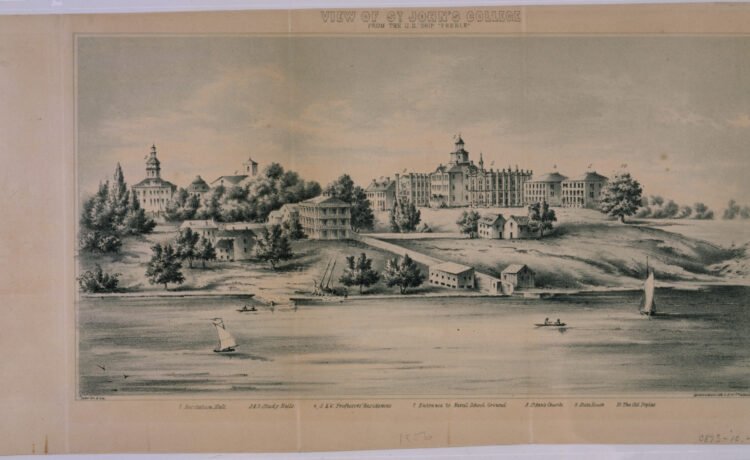

Known as King William’s School in its early years, the Maryland Assembly formally chartered the institution as St. John’s College in 1784. Five buildings constructed on the campus predate 1864, the year Maryland abolished slavery: McDowell Hall (1789), Humphreys Hall (1837), Chase-Stone House (1857), Pinkney Hall (1858), and the Paca-Carroll House (1855). Given that slavery was omnipresent in Maryland prior to the Civil War, St. John’s College undoubtedly used enslaved people as a source of wealth and labor. Unfortunately, records frequently do not provide much detailed information on slave labor in construction projects. But as historian Ira Berlin has said: “[i]f slaves didn’t lay the bricks, they made the bricks. If they didn’t make the bricks, they drove the wagon that brought the bricks. If they didn’t drive the wagon, they built the wagon wheels.” Thus, a literal view of whose hands constructed a building can obscure the larger, more important concept that enslaved people were essential to the creation of the American built landscape.

In 2023 and 2024, with funding from the Maryland Historical Trust’s (MHT’s) Historic Preservation Non-Capital Grant Program, St. John’s College embarked upon a broad project to examine its 329-year history. The project was spearheaded by the College History Task Force, established to research the school’s history in relation to indigenous and enslaved people and make recommendations on how the past should be acknowledged. The grant-funded endeavor included two components: (1) the architectural survey of historic buildings and objects on the school’s Annapolis campus and (2) research into the role of enslaved people in the development of the campus and to the people for whom campus buildings were named.

“Architectural survey” is simply the process of gathering information on historic properties, and surveys conducted in the state of Maryland are incorporated into the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties (MIHP), which researchers can access via the Medusa application on MHT’s website. With the MHT grant funding, St. John’s College hired the services of E.H.T. Traceries, a firm of architectural historians. Traceries completed surveys of sixteen buildings, two monuments, and one demolished site feature (the Liberty Tree, which was irreparably damaged in 1999). The surveyed buildings include McDowell Hall, which served as the first building on St. John’s campus, and Pinkney Hall, which was a dormitory and faculty boarding house constructed from 1855 to 1858. The research component of the project concluded that it is likely that enslaved people constructed the college’s early buildings.

The original college charter gifted a partially-constructed building in Annapolis (once intended to be the governor’s residence) to house classrooms and dormitories for faculty and students. Wealthy local men, including Charles Carroll of Carrollton, William Paca, and Thomas Stone, donated the majority of the funding necessary to complete the building, now known as McDowell Hall. Joseph Clarke, who served as the designer of the State House dome, was in charge of finishing construction. These men all benefited from slavery: the funders derived their wealth by exploiting the labor of enslaved people, primarily in agriculture, and Joseph Clarke and his wife Isabella enslaved two people at their home in Annapolis, per the 1783 Federal Direct Tax Lists. The building was formally named McDowell Hall in 1857 in honor of the first president of St. John’s College, John McDowell. From historic records, it appears that John McDowell enslaved at least one individual, Joseph Williams, during his tenure at St. John’s from 1790 to 1806. McDowell left St. John’s to take a position at the University of Pennsylvania, and it appears that Williams accompanied him there, despite a Pennsylvania law forbidding the transport of enslaved people into the state. Perhaps because of this law, McDowell manumitted Williams a year later in 1807.

Architect Nathan G. Starkweather designed Pinkney Hall, and local builders Daniel M. Sprogle and Daniel H. Caulk oversaw its construction from 1855 to 1858. It served as a dormitory and faculty boarding house. Tax assessment records indicated that Sprogle personally enslaved five people (a man, woman, and three children). It is unclear, however, as to whether Sprogle employed slave labor in his construction projects. According to available historic documentation, it does not appear that Caulk was an enslaver. The building’s namesake is politician and lawyer William Pinkney, who attended King William’s School. Pinkney was an enslaver, although ironically he began his career as an outspoken critic of slavery. His views transformed, however, and in his later years as a U.S. Senator for Maryland he supported the spread of slavery into new territories and states and maintained that the Federal government did not have the right to abrogate slavery, which was supposedly under states’ purview.

In addition to the era of slavery, the project also conducted some targeted research on the college’s twentieth-century history. A particularly dark chapter of the past occurred in 1906, when St. John’s College students participated in the lynching of Black man, Henry Davis (according to contemporary newspaper accounts). Further, the racial integration of St. John’s College was difficult and slow. Prompted by the rejection of African American student Willie Washington in 1944, white students at St. John’s voted on a resolution to welcome students of any race or color to the school. Martin Dyer was the first Black student admitted to St. John’s in 1948, but he remained the sole African American enrolled at the college during his four-year education.

The full report can be found on MHT’s website, as well as the website of the St. John’s College History Task Force. They would like to take future steps to acknowledge this difficult past, and have requested ideas from students, alumni, faculty, and community members. Other Maryland institutions have a history with slavery and are also undertaking this important work.