Yves here. Rajiv Sethi makes the point that successfully bullying Colombia with tariff threats over deportation flights is the sort of show of crude power in a very uneven situation that looks likely to generate resistance, particularly from bigger players.

This tactic is backfiring with Trump’s bizarre aggressive statements towards Putin about Ukraine. The Ukraine-skeptic comment sphere, which includes quite a few Trump fans, is speaking almost with one voice as to what a dumb move this is. It does nothing to improve the US position in negotiations (charitably assuming they happen) and show Trump to be overeager (as in further weakening his stance) and wildly uninformed. And recall Trump threw away additional leverage he might have had by turning on the EU and NATO, who even if they can’t save Ukraine, could still make life difficult for Russia (think Kalingrad and the Baltic Sea, for starters). And while the US can buy coffee from places other than Colombia, experts have pointed out that the very few things the US still buys from Russia, like enriched uranium, are substances we need (and are thus also likely price inelastic too, so it’s not as if those small Russian sales would suffer).

And that’s before looking at the coffee trade through a broader lens:

If you’re wondering why we use the colorful phrase “social-democracy is the left wing of fascism,” try to understand how ghoulish it is to see this through the lens of “Americans will have to pay more for coffee.”

Coffee is one of the most egregious examples of unequal exchange. https://t.co/GUp0syjrhq

— A. V. Dremel 🔻 (@BmoreOrganized) January 27, 2025

Mind you, even though a lot of this looks like Trump engaged in dominance display, he has surrounded himself with men who roll the same way (think Tom Homans, Sebastian Gorky and Steve Witkoff). We’ll see soon enough what happens when this sort of threat display meets well-armed targets.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University &; External Professor, Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at his site

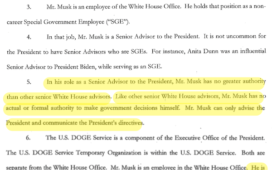

The dispute between Colombia and the United States regarding deportation flights appears to have been resolved, and the threatened trade war between the two countries has been averted for the time being. The Colombian president wanted returning citizens to be treated with dignity and respect. Perhaps some concessions were made in this regard, though his government’s official statement does not contain specifics. The White House is declaring victory.

The American economy is about thirty times as large as that of Colombia. With the possible exception of cut flowers and coffee, turning to other suppliers for imported goods would have been quite easy. We are Colombia’s largest trading partner by far, accounting for a quarter of its exports. Meanwhile Columbia absorbs just one percent of our total exports. A prologed trade war would have imposed some costs on American consumers, especially with Valentine’s Day approaching. But it would have been utterly devastating for Colombia.

Furthermore, the range of threats extended far beyond tariffs—some Colombian nationals working for the World Bank had their visas revoked and were deportedduring the standoff. I suspect that this kind of heavy-handed tactic will be used with some frequency over the next few years.

Such exercise of raw power can bring other countries (and domestic institutions) to heel. It can produce decisive victories in the short run. But it can also have significant long term consequences, affecting patterns of trade and geopolitical alliances.

As an example, consider the oil price shocks of the 1970s, driven in part by the exercise of market power by the OPEC countries. The global price of crude oil quadrupled in January 1974 and inflation in the US reached double digits during that year. A second shock in 1979 pushed inflation even higher, and it took a severe recession engineered by the Federal Reserve to bring it back down. Meanwhile oil exporters enjoyed windfall profits even while slowing the depletion of their reserves.

Over time, though, a number of adjustments took place. People switched to smaller and more fuel-efficient vehicles. Japanese automakers (led by Toyota, Honda, and Nissan) met this demand and made major inroads in global markets. Their share of the US automobile market was negligible in 1970, but had risen to more than one-fifth a decade later. Several countries moved towards energy independence, with France achieving it—based largely on nuclear power—and becoming a major energy exporter. High prices induced non-member states to step up production, and tempted member states to periodically violate agreements to restrict output. All these changes progressively weakened the power of the cartel.

The shock experienced by Columbia is a lesson to others who would defy the Trump administration in any way—in fact it is intended as precicely as such a warning. The logic here is similar to that of the chain store paradox. Convince enough people that you are willing to hurt yourself in order to hurt them more, and you will often get your way.

But as with the oil price shocks, there will be long term consequences. Colombia (and other countries watching closely) will want to reduce their vulnerability to such actions, by changing their patterns of trade and their geopolitical alliances.

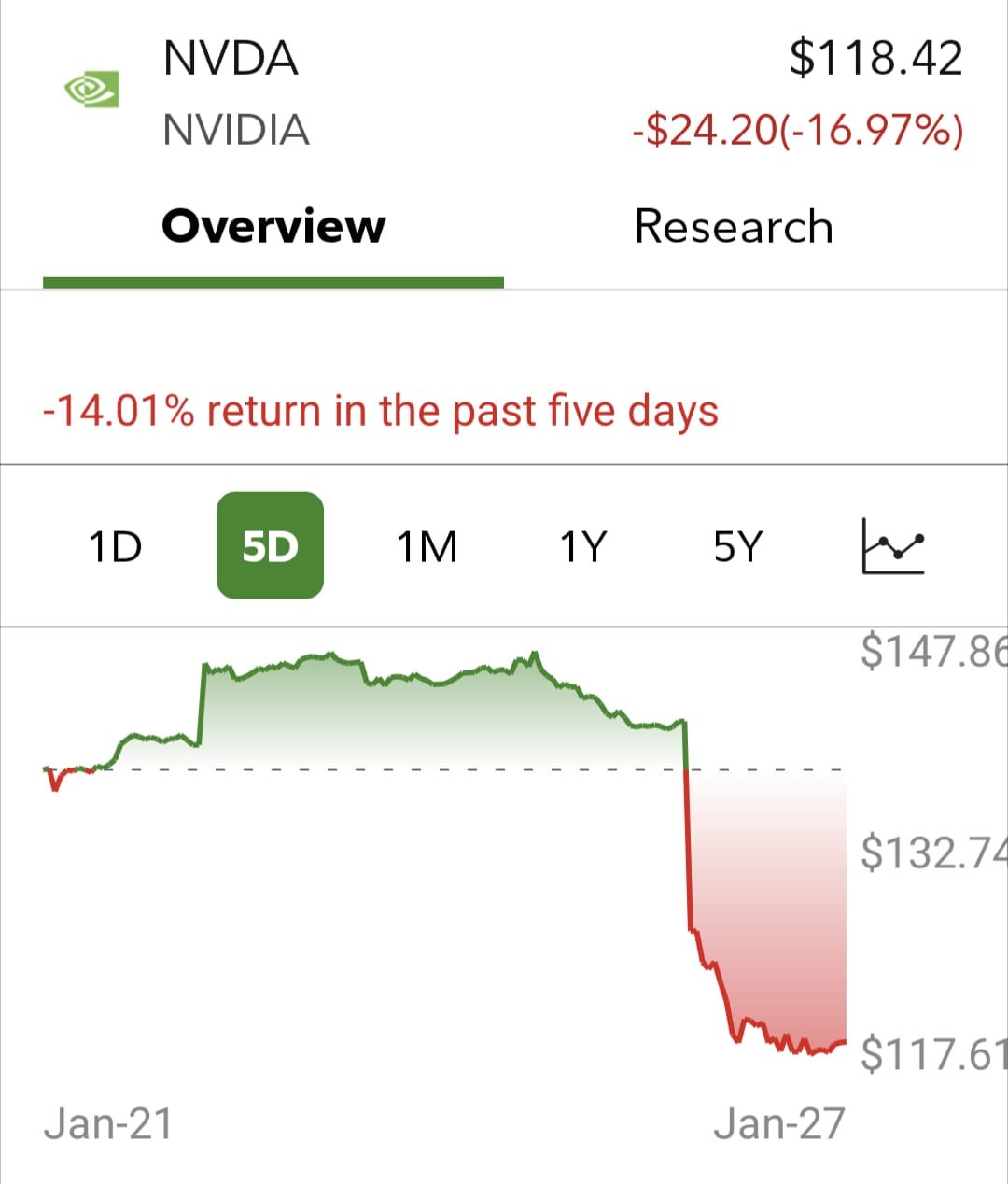

The only serious countervailing force in global affairs at the moment is China, which demonstated its capacity for shifting the technological frontier with the release of DeepSeek just a few days ago. The high-performance chip maker Nvidia lost $600 billion in value in a single day as anticipated demand for its most lucrative products was revised downwards:

These two geopolitical shocks—the humiliation of a relatively small trading partner and a shot across the bow by a much larger one—both have implications for what the future might bring. The needless humiliation will push Colombia and other potential victims into the arms of an emerging global power, and the embrace will be reciprocated. While champagne corks are popping to celebrate a small victory against a weak adversary, quiet celebrations may also be underway on the other side of the world.