The abstract from article forthcoming in the Journal of International Money and Finance.

We begin by examining determinants of aggregate foreign exchange reserve holdings by central banks (size of issuing country’s economy and financial markets, ability of the currency to hold value, and inertia). But understanding the determination of reserve holdings probably requires going beyond the aggregate numbers, instead observing individual central bank behavior, including characteristics of the holding country (bilateral trade with the issuing country, bilateral currency peg, and proxies for bilateral exposure to sanctions), in addition to the characteristics of the reserve currency issuer. On a currency-by-currency basis, US dollar holdings are somewhat well explained by several issuer characteristics; but the other currencies are less successfully explained. It may be that the results from currency-by-currency estimation are impaired by insufficient sample size. This consideration offers a motivation for pooling the data across the major currencies and imposing the constraints that reserve holdings are determined in the same way for each currency. In this setting, most economic determinants enter with significance: economic size as measured by GDP, bilateral currency peg, and bilateral trade share. While one geopolitical factor (congruence in voting in the UN) is typically significant in the expected manner (with the exception of the US dollar), the other geopolitical factor (sanctions) does not enter with significance.

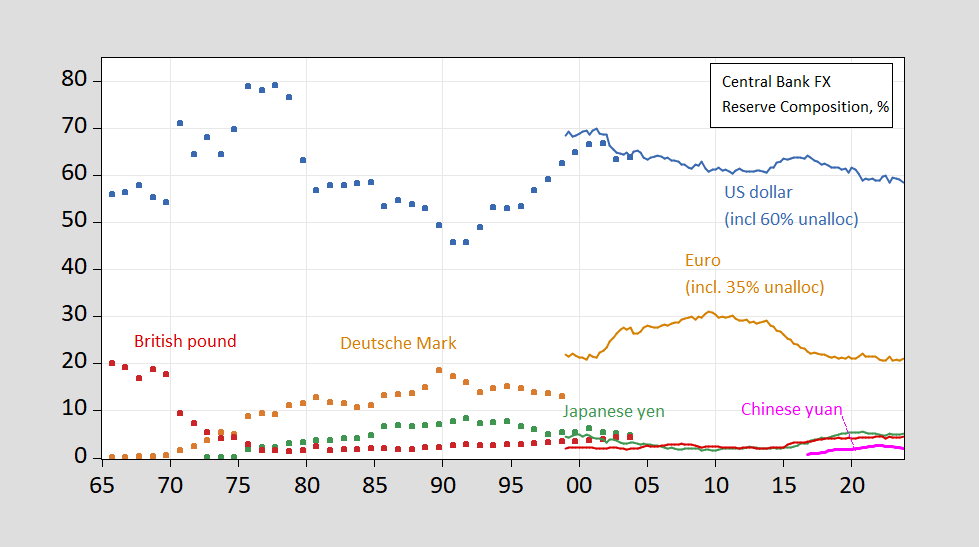

Here’s a picture of the aggregate currency shares, from the IMF’s COFER database, updated data released on June 11th.

Figure 1: Share of foreign exchange reserves held by central banks, in USD (blue), EUR (orange), DEM (tan squares), JPY (green), GBP (sky blue), Swiss francs (purple), CNY (red). For 1999 data onward, estimates based on COFER data, and apportionment of unallocated reserves, described in text. Source: Chinn and Frankel (2007), IMF COFER accessed 6/20/2024, and author’s estimates.

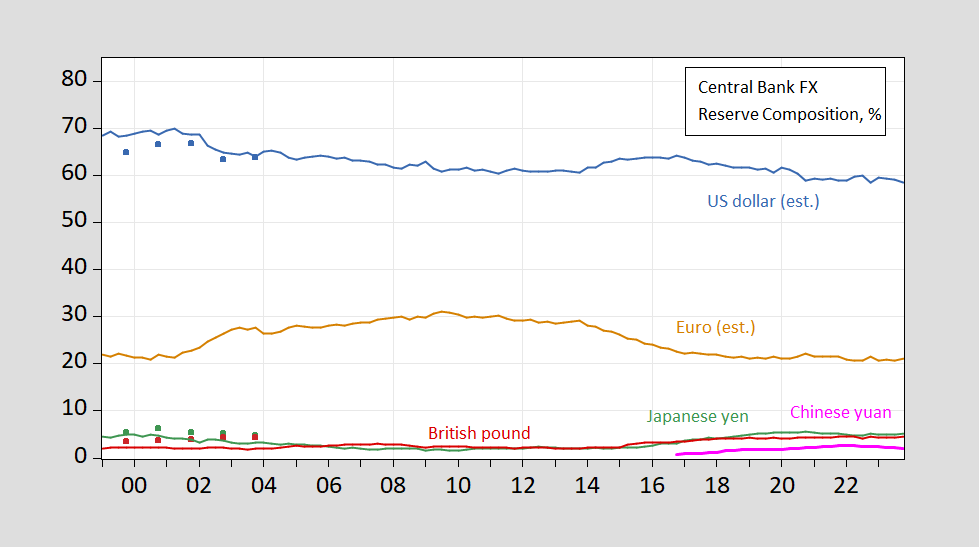

And here’s a detail, for 1999 onward:

Figure 2: Share of foreign exchange reserves held by central banks, in USD (blue), EUR (orange), JPY (green), GBP (sky blue), Swiss francs (purple), CNY (red). For 1999 data onward, estimates based on COFER data, and apportionment of unallocated reserves, described in text. Source: Chinn and Frankel (2007), IMF COFER accessed 6/20/2024, and author’s estimates.

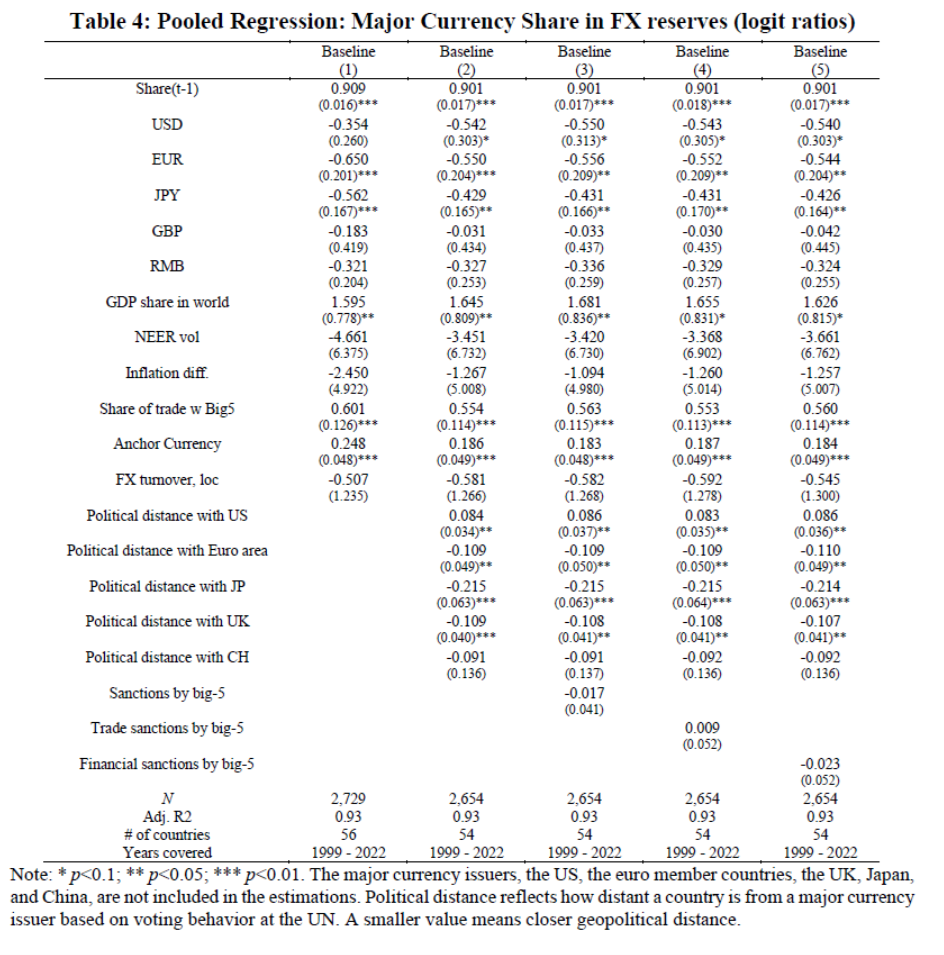

Equations used to estimate aggregate shares pre-EMU are pretty useless in predicting shares now. Hence, in this new paper, we rely on individual central bank data to estimate the determinants of shares. The results of a pooled cross-country cross-currency, unconstraining the geopolitical distance coefficient to vary across currency, are reported in Table 4.

Source: Chinn, Frankel, Ito (forthcoming, JIMF).

Following the results in Chinn and Frankel (2007), we find economic size matters, as well as inertia. While we find store of value measures (inflation, exchange rate volatility) have a negative impact, those effects are not statistically significant. This special data set (central bank by year) allows us to investigate the impact of trade flows and peg, which turns out to be important. We replicate the finding obtained by Goldberg and Hannaoui (2024) that more geopolitically distant countries (as measured by coincidence in UN GA voting) hold greater dollar shares, while the reverse is true for the other currencies. While financial sanctions have a negative impact, the measured sensitivity is not statistically significant.

While we don’t explicitly record how dollar shares have declined, it’s useful to note that other studies (see Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell (2024), and references therein) have documented that the slack is not in general being mostly take up by the RMB, but other unconventional currencies.

See also Eswar Prasad’s recent Foreign Affairs piece, the Third annual Fed-FRBNY conference on the international roles of the dollar, Kamin and Sobel (2024), Atlantic Council “Dollar Dominance Monitor”.