Western economists and financiers have so regularly predicted a crash or zombification outcome to China’s spectacular run of growth that it’s too easy to dismiss stories about deflation risk as yet more Chicken Littledom. But that would be a mistake. The warning sign this time is coming not from tea-leaf reading prognosticators but the domestic investor dominated, very large and therefore not manipulable Chinese government bond market. Its plunge in yields to deflation-warning levels is a sign of profound concern about growth prospects. And if actual or borderline inflation becomes entrenched, it’s hard to reverse.

Before we turn to the evidence, a wee bit of background. As much as inflation-whacked Americans might find it hard to believe, deflation is far more destructive than inflation. Falling prices across most of an economy signals weak demand. That can easily become self-reinforcing. Businesses and consumers put off spending because they aren’t certain if and when things will pick up. Continued diminished outlays results in less hiring and eventually reductions in hours and layoffs, producing yet more belt-tightening. A trend of declining prices leads directly to even more savings. After all, if you don’t buy something now, it will probably be cheaper later. Since future dollars are worth less than present dollars, prices of risk assets like stocks and housing tend to fall, making those holders feel poorer, once again whacking spending.

And a further accelerant is debt dynamics. As the general price level falls, the real value of debt increases. That in combination with a flagging economy means more business failures, and so with that, less commercial spending, more job losses and a further contraction in economic activity. See Irving Fisher’s classic paper for details.

Since Chinese economic statistics are often criticized as unreliable. For instance, Michael Pettis has explained long-form how their GDP figures are not comparable to those in the West.1 When I started this site, analysts would regularly say they did not use reported GDP but instead uses electricity consumption. A few years later, for reasons I don’t recall clearly, those figures came to be regarded as fudged.

So one reason for a pessimistic bias among China commentators has not been Orientalism (although that plays a role) but that key Chinese data really does have a bias, much more than Western stats, to exaggerate, so that when any negative figures or factoids appear, they are deemed as “truer” due to looking like admissions against interest.

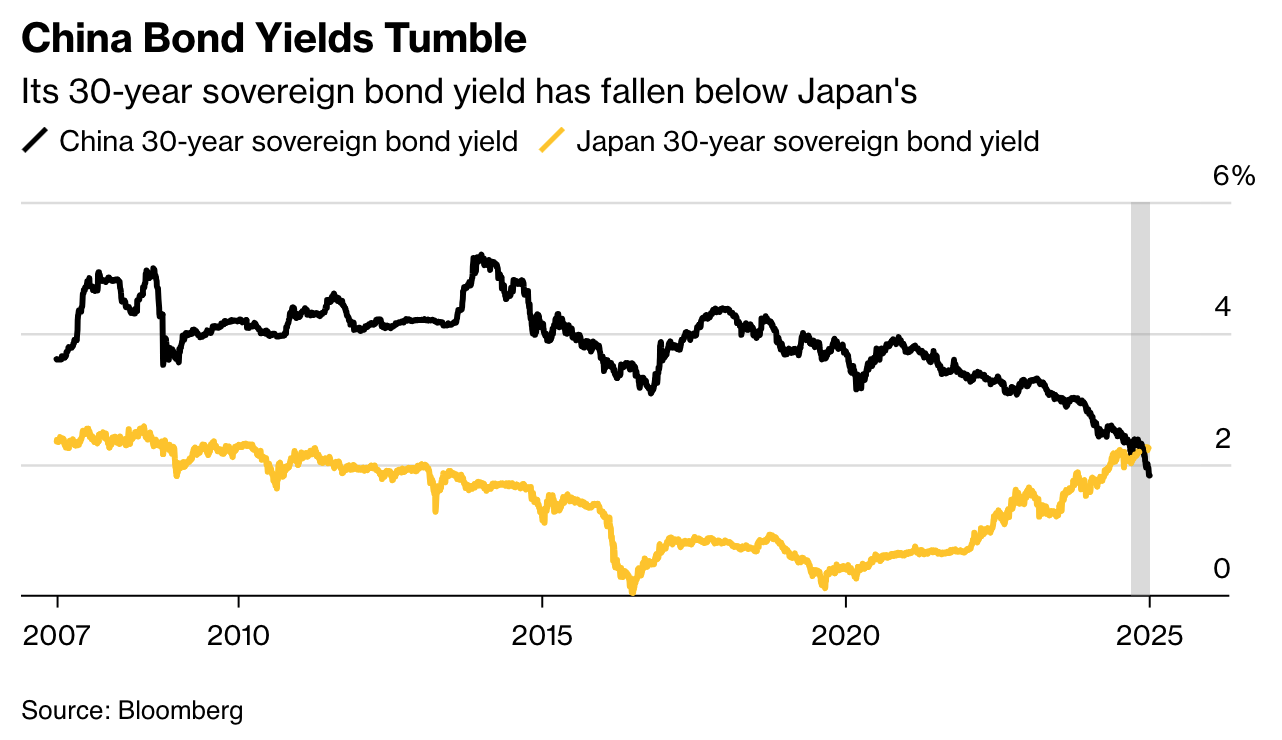

To the bond market warning sign, and then other reasons to think that deflation and zombification risk in China is real. From Bloomberg:

Investors in China’s $11 trillion government bond market have never been so pessimistic about the world’s second-largest economy, with some now piling into bets on a deflationary spiral mirroring Japan’s in the 1990s..

The plunge, which has dragged Chinese yields far below levels reached during the 2008 global financial crisis and the Covid pandemic, underscores growing concern that policymakers will fail to stop China from sliding into an economic malaise that could last decades….

In a sign of how seriously investors are taking the risk of Japanification, China’s 10 largest brokerages have all produced research on the neighboring country’s lost decades….

While an echo of post-bubble Japan is far from certain, the similarities are hard to ignore. Both countries suffered from a real estate crash, weak private investment, tepid consumption, a massive debt overhang and a rapidly aging population. Even investors who point to China’s tighter control over the economy as a reason for optimism worry that officials have been slow to act more forcefully. One clear lesson from Japan: Reviving growth becomes increasingly difficult the longer authorities wait to stamp out pessimism among investors, consumers and businesses.

“The bond market is already telling the Chinese people: ‘you are in balance sheet recession’,” said [Richard] Koo, chief economist at Nomura Research Institute. The term, popularized by Koo as a way to explain Japan’s long struggle with deflation, occurs when a large number of firms and households reduce debt and increase their savings at the same time, leading to a rapid decline in economic activity…

The problem is that the policy prescriptions so far haven’t been nearly ambitious enough to reverse falling prices, with weak consumer confidence, a property crisis, an uncertain business environment combining to suppress inflation. Data due Thursday will likely show consumer price growth remained near zero in December while producer prices continued to slide. The GDP deflator — the broadest measure of prices across the economy — is in its longest deflationary streak this century.

One issue with the latest Chinese stimulus approach is that China has been trying to shift from growth via debt-fueled investment in real estate to tech industry growth. The problem is that this still amounts to focusing on increasing production as opposed to consumption. Even though many Twitterati and reader pooh-pooh the notion that there is such a thing as overinvestment, have a look at the railroad industry in the mid-late 1800s which was rife with overbuilding and bankruptcies, or now, the office space market in most US cities, which is in considerable overcapacity due to work at home. Too much output in relationship to demand for product and services results in aggressive competition for the existing buyers and so either price cutting or covert discounting via freebies. Enough of that and you get capacity cutbacks via operation closures and/or bankruptcies. The output level (ex continuing government subsidies) eventually contract to a level that can be supported by sales volumes.

But China’s policy-makers seem to have a case of having changed their minds but not their hearts. Even though many agree that the Middle Kingdom needs to shift to a more consumer-driven economic model, China recoils from taking the big step to getting consumers to save less, which is stronger and more extensive social safety nets. Consider:

To promote common prosperity, we cannot engage in ‘welfarism.’ In the past, high welfare in some populist Latin American countries fostered a group of ‘lazy people’ who got something for nothing. As a result, their national finances were overwhelmed, and these countries fell into the ‘middle income trap’ for a long time. Once welfare benefits go up, they cannot come down. It is unsustainable to engage in ‘welfarism’ that exceeds our capabilities. It will inevitably bring about serious economic and political problems.

— Xi Jinping

If anything, China’s meager social safety net has become more threadbare of late. From the Hudson Institute:

Local governments are responsible for more than 90 percent of China’s social services costs but only receive about 50 percent of tax revenues. For decades, they have relied on land sales and related real estate revenues to meet their budgets, but both sources have declined precipitously as the housing boom has reversed course. According to the Rhodium Group, more than half of Chinese cities face difficulties paying down their debt, or even meeting interest payments, severely limiting their resources for social services. China’s total debt levels are estimated to be around 140 percent of GDP, limiting budget flexibility for supporting social services.

While the bond market data is arresting, other statistics point in the same direction. Youth unemployment is high, reported recently at between 16% and 19% until China stop publishing that date series. Prices have fallen for six consecutive quarters. One more would put it at China’s modern record, during the 1990s

Asian crisis.

Bloomberg, in a different story right before year end, noted:

Prices rocketed in the US and other big economies when they reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic, as pent-up demand coincided with shortages in the supply of many goods. Predictions the same would happen in China proved to be wrong. Consumer spending power is weak and a real estate slump has dented confidence, holding people back from buying big-ticket items.

A tightening of regulations on high-paying industries from tech to finance has led to lay-offs and salary cuts, further dampening the appetite for spending. A policy push to develop manufacturing and high-tech goods led to increased production, but demand for the goods has been weak, forcing businesses to mark down prices….

Transport has been the biggest drag on consumer prices lately, driven mostly by falling car and gasoline prices. Carmakers including BYD Co. have asked suppliers to cut prices, signalling an intensified price war in China’s auto-market. For the broader economy, real estate and manufacturing are the sectors that recorded the deepest contraction in prices in the first three quarters of 2024, based on an industry-level gross domestic product deflator calculated by Bloomberg. A persistent property bubble has led to a housing inventory glut, while the government’s support for manufacturing — from cheap loans to favourable tax policies — has increased the supply of goods that consumers are hesitant to purchase.

These and other articles have pointed out that China’s recent stimulus measures are weaker than past ones. They are also directed to consumers only to a limited degree, with some aid to students and the poor, subsidies for auto and appliance purchases, pressure on banks to lend for the purpose of completing stalled developments, and exhortations to local governments to purchase unsold residential units and convert them to public housing (the latest stimulus package does include local government debt relief, so they might have enough budget room to do that to at least a degree). The Bank of China has also been cutting rates over the last two years. But as we have repeatedly pointed out, putting money on sale does not lead businesses to invest more unless their business is leveraged speculation (like financial traders, banks, private equity and often real estate developers). Enterprises will borrow to fund growth if they see opportunity; the cost of money can be a constraint but cheap money isn’t sufficient cause in and of itsself for most managers to commit to an expansion plan. As we saw with ZIRP, the side effects of a long period of too-low interest rates is income inequality and a painful exit, since at very low rates, the financial asset price whackage of rate increases is much greater than at “normal” levels (say 2% or higher policy rates).

So far, China has done an excellent job of escaping the usual fate of economies that move from being export and investment-lead to consumption-lead, that of suffering a serious financial crisis. Has its luck finally run out?

_____

1 The eye-catching start to his January 2019 article:

The Chinese economy is not growing at 6.5 percent. It is probably growing by less than half of that. Not everyone agrees that the rate is that low, of course, but there is nonetheless a running debate about what is really happening in the Chinese economy and whether or not the country’s reported GDP growth is accurate….

….when you speak to Chinese businesses, economists, or analysts, it is hard to find any economic sector enjoying decent growth. Almost everyone is complaining bitterly about terribly difficult conditions, rising bankruptcies, a collapsing stock market, and dashed expectations. In my eighteen years in China, I have never seen this level of financial worry and unhappiness.