(The Conversation) — Since JD Vance became the Republican vice presidential nominee, his record has come under intense scrutiny. In a 2021 interview, for example, Vance criticized Vice President Kamala Harris as “one of a bunch of childless cat ladies” who lived “miserable lives” and were forcing their misery on the rest of the country, even though they had no “direct stake” in the country’s future without offspring.

The term cat lady is often used today as a derogatory term for women with no children and who are believed to be reclusive as well as obsessed with their pets. For the record, Harris is the stepmother of her husband’s two children. In addition, the choice to bear children or not has nothing to do with women’s contributions to American society.

Moreover, Vance’s views on childless women are sharply at odds with the attitude of his present Catholic faith. As a scholar of medieval Catholicism, I know that Catholic history is full of childless women respected for their work, many of them members of religious communities. They often contributed to lasting social and cultural change. In fact, the very existence of women’s religious communities is a testament to the value Catholicism puts on childless women’s lives.

Monastic women

The monastic movement, which originated in Egypt in the early days of Christianity, was rooted in the desire of some men and women to focus on solitude and prayer as a way to lead a more perfect Christian life. In fact, choosing a life of celibacy was considered a higher spiritual calling, for single women as well as for men. They left the towns and cities to live in prayerful solitude in the wilderness.

Some of these men and women lived alone, as hermits; others joined together in isolated communities of all men or all women.

The dominant form of communal monasticism in medieval Western Christianity from the sixth century on was Benedictine monasticism, which organized monastic life, prayer and work according to a text written by the Italian monk St. Benedict of Nursia: the Rule of Saint Benedict. Monasteries of childless women as well as of childless men followed this rule, pledging themselves to chastity as well as poverty and obedience. The Benedictine life still called for withdrawal from society but also stressed hospitality for guests and visitors.

Like the monks, who taught boys, Benedictine nuns became known for teaching young girls, often the daughters of noblemen and other influential families. Some of the girls stayed to become nuns themselves, from personal choice or out of obedience to their parents. Others returned to their families, usually to marry.

European movements

But marriage or entering a monastery were not the only choices for medieval women. Some joined monasteries as lay sisters who ran errands outside of monasteries for the cloistered nuns. Others decided to remain unmarried and care for elderly parents or other relatives.

By the 12th century, single women could also choose to live as solitary hermits, not in a desert or forest but in the middle of a town. These women were known as anchoresses, living in small, single-roomed cells.

These cells, or anchor-holds, were built onto the side of the local church, with two or three windows looking into the church or a side garden. A female servant would take care of errands outside of the anchoress’s cell. Anchoresses could be financially supported by their own wealth or by donations from others.

Anchoresses were considered metaphorically dead to the outside world; part of the ritual for enclosing an anchoress echoed a funeral service. They committed to live in their cells for the rest of their lives.

However, they did become important parts of the wider community. They often did sewing and embroidery, either for use in the church’s worship or to be given to the poor or sold. Anchoresses were also consulted by other women for advice, visited by pilgrims asking for prayers, or asked to teach small groups of girls. Interactions with men were severely limited and almost never one on one.

During the 12th century, other single childless women in parts of Europe began to come together in less formally organized groups. Known as beguines, they did not take permanent religious vows but privately pledged to live lives of poverty, chastity and obedience through informal, temporary vows.

By the 14th century, they usually lived together in small, separate sections of towns and cities called beguinages. Beguines served their local communities by working in existing hospitals, acting as midwives, visiting the sick and the poor, taking in orphans and educating children.

As an independent movement of women without much male supervision, however, they came under suspicion in the 13th century from some church authorities who began to fear that they were teaching heretical ideas. Many were interrogated and and at least one was executed by being burned at the stake during the Inquisition. They gradually diminished in number during the Reformation.

Contributions in education

In the 19th century, women’s religious orders experienced a remarkable expansion. Both old and new orders spread widely beyond Europe and made an enormous impact in the young United States. One important area was education. For example, the Religious of the Sacred Heart, founded after the chaos of the French Revolution by St. Madeline Sophie Barat in 1800, established schools for girls in several cities in the United States and Canada.

Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini.

Wikimedia Commons

At the request of the bishop of Louisiana, she sent a small group of sisters, led by St. Rose Philippine Duchesne, to the United States in 1818 to set up a school for French and Native American children. Today, there are 25 American schools, part of a global network of Sacred Heart Schools in over 40 countries.

Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini, who founded the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Italy, worked with new immigrants to the United States. She established schools and orphanages not just in North America but in Central and South America as well. Mother Cabrini was canonized in 1946 and is the patron saint of immigrants.

Caring for the sick

Catholic sisters have also been very visible in health care in Europe and the United States.

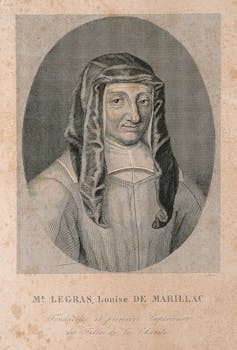

Louise de Marillac.

Wellcome Collection, Artist Louis Hercule Sisco, 1778-1861.

Beginning in the 13th century, Augustinian nuns, following a rule of life based on the teaching of St. Augustine, had cared for the sick for centuries in one of the oldest hospitals in Europe: the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. Later, a new order of French sisters, the Daughters of Charity, was founded by St. Vincent de Paul and St. Louise de Marillac in 1633. They also served as nurses in the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. Today, they still focus on health care for the elderly and disabled, as well as education, in 94 countries, including the United States.

Inspired by their example, the American widow and Catholic convert Elizabeth Ann Seton founded the Sisters of Charity in Maryland in 1809, which continued with the work of these French sisters in the United States.

Other religious orders of nuns, such as the Irish Sisters of Mercy, set up hospitals in the 19th century in Pittsburgh and San Francisco. Like the Sisters of Charity, they continue to work in both nursing and education.

However, there have been scandals. For example, an institution run by the Bon Secours Sisters in Ireland was the site of terrible abuses. The bodies of almost 800 babies and children were secretly buried at the Bon Secours Mother and Baby home in the mid-20th century. And for almost a century, Native American children were subjected to physical and sexual abuse in schools run by Benedictine nuns in Minnesota.

Since then, both the Bon Secours Sisters and the Benedictines have issued apologies. These abuses and others like them must be eliminated and acknowledged as a taint upon 15 centuries of positive work.

Contemporary American society is improving in terms of valuing the contributions of both mothers and childless women equally, irrespective of their religious affiliation. But it is important to note that, for centuries, while marriage and children were important, childless women in the Catholic Church were valued for their contributions.

(Joanne M. Pierce, Professor Emerita of Religious Studies, College of the Holy Cross. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()