It may well be that the major pivot points of history are only visible to those around the bend. For those of us immersed in the present—for all of its deafening sirens of violent upheaval—the exact years future generations will use to mark our epoch remain unclear. But when we look back, certain years stand out above all others, those that historians use as arrestingly singular book titles: 1066: The Year of Conquest, 1492: The Year the World Began, 1776. The first such year in the 20th century gets a particularly grim subtitle in historian Paul Ham’s 1914: The Year the World Ended.

It sounds like hyperbolic marketing, but that apocalyptic description of the effects of World War I comes from some of the most eloquent voices of the age, whether those of American expatriates like Gertrude Stein or T.S. Eliot, or of European soldier-poets like Wilfred Owen or Siegfried Sassoon.

In France, the horrors of the war prompted its survivors to remember the years before it as La Belle Epoque, a phrase—wrote the BBC’s Hugh Schofield in the centenary essay “La Belle Eqoque: Paris 1914,”—that appeared “much later in the century, when people who’d lived their gilded youths in the pre-war years started looking back and reminiscing.”

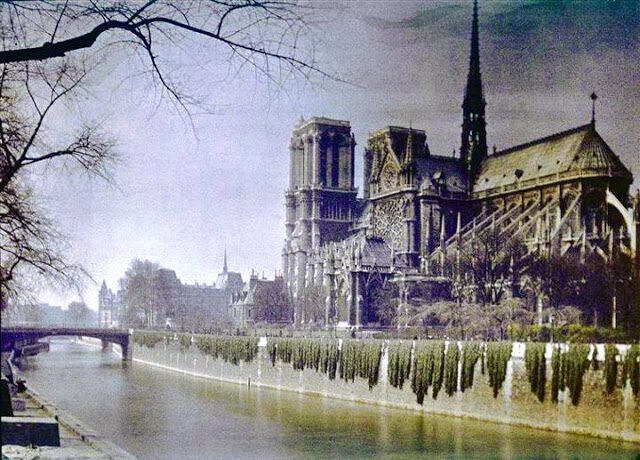

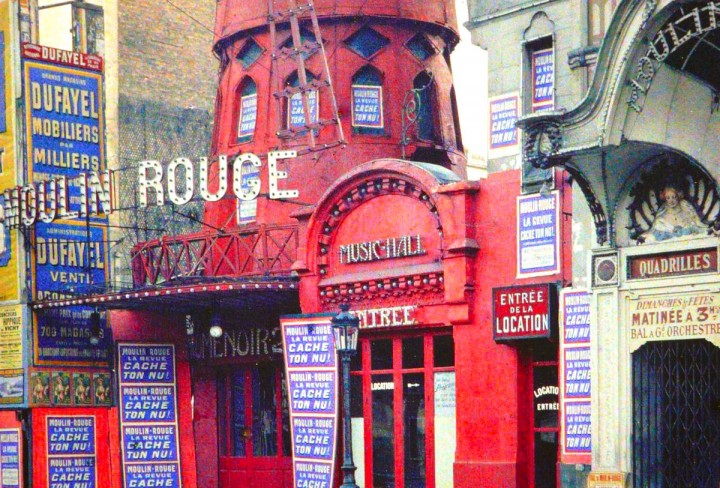

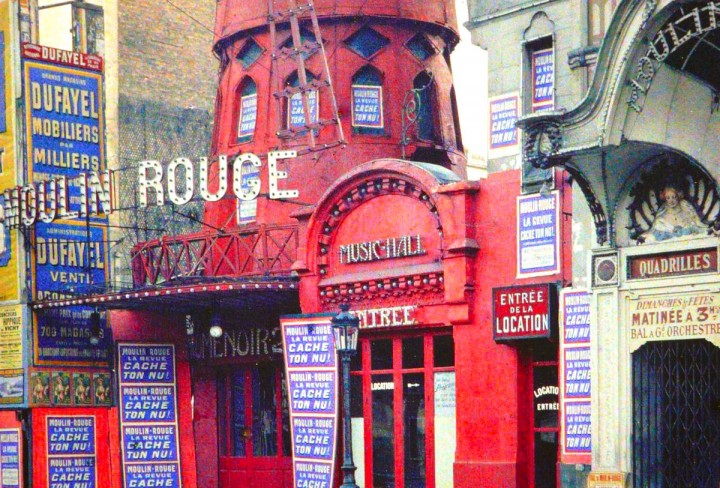

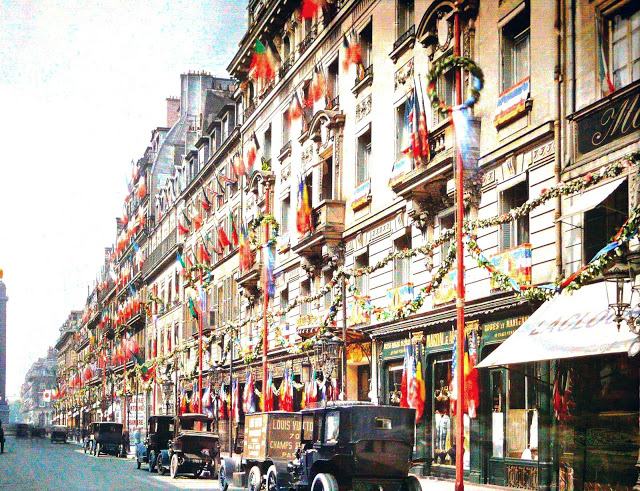

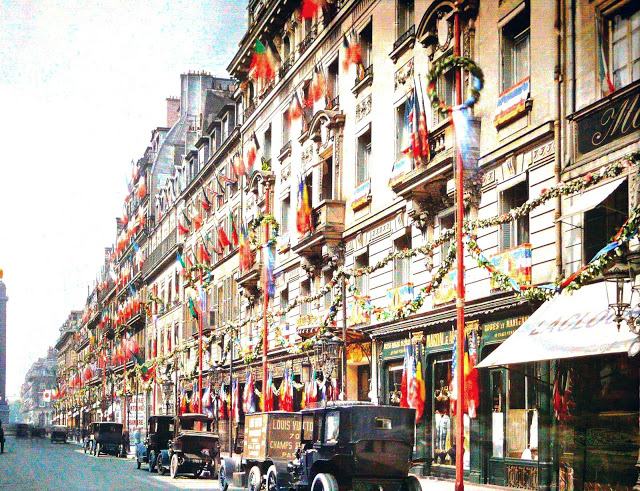

We’re used to seeing the period of 1914 in grainy, dreary black-and-white, and to seeing nostalgic celebrations of La Belle Epoque represented graphically by the lively full-color posters and advertisements one finds in décor stores. But thanks to the full color photos you see here, we can see photographs of World War I‑era Paris in full and vibrant color—images of the city 110 years ago almost just as Parisians saw it at the time. Icons like the Moulin Rouge come to life in bright daylight, above, and lighting up the night, below.

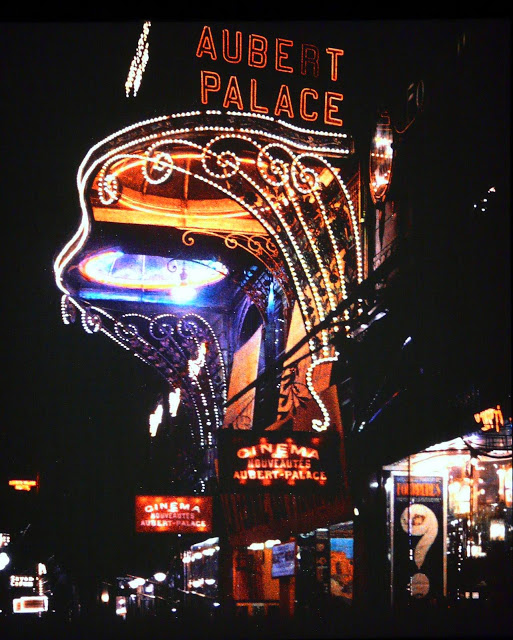

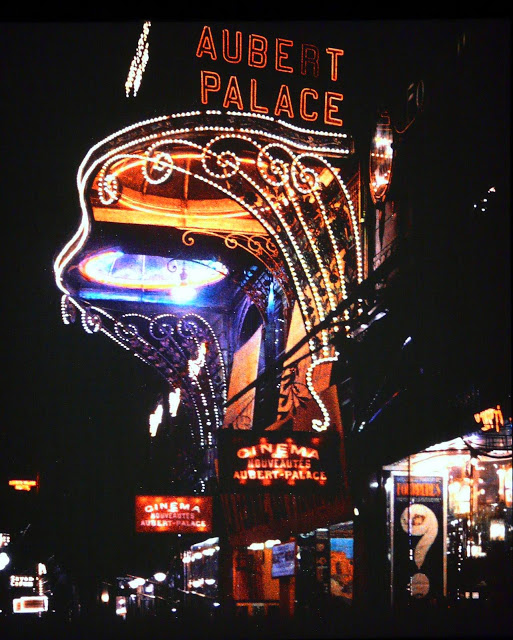

Early cinema Aubert Palace, below, in the Grands Boulevards, shimmers beautifully, as does the art-deco lighting of the Eiffel Tower, further down.

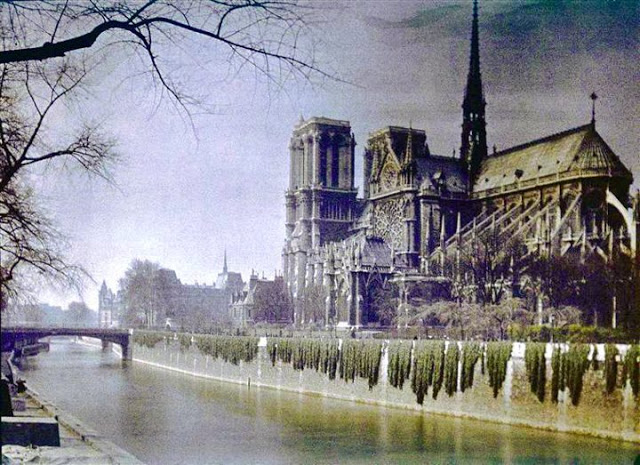

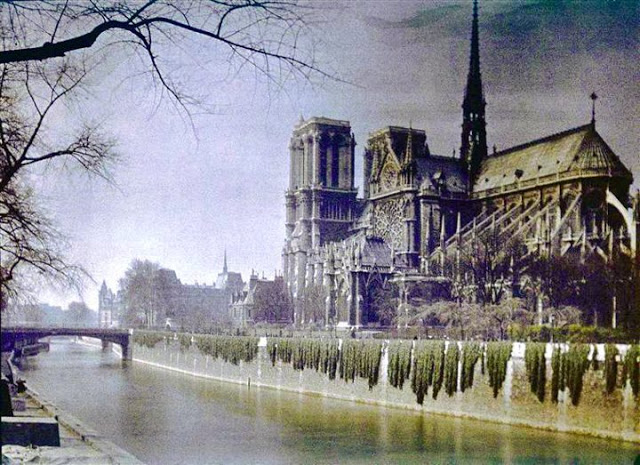

Below, hot air balloons hover in the enormous Grand Palais, and further down, a photograph of Notre Dame on a hazy day almost looks like a watercolor.

The photographs were made, writes Messy N Chic, “using Autochrome Lumière technology between 1914 and 1918 [a technique developed in 1903 by the Lumière brothers, credited as the first filmmakers]…. [T]here are around 72,000 Autochromes from the time period of places all over the world, including Paris in its true colors.”

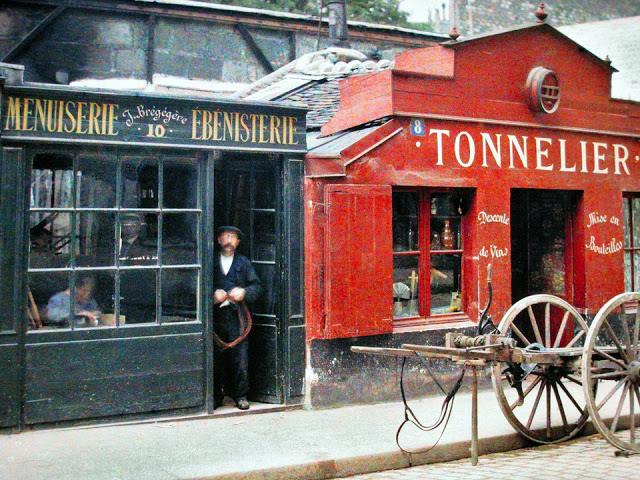

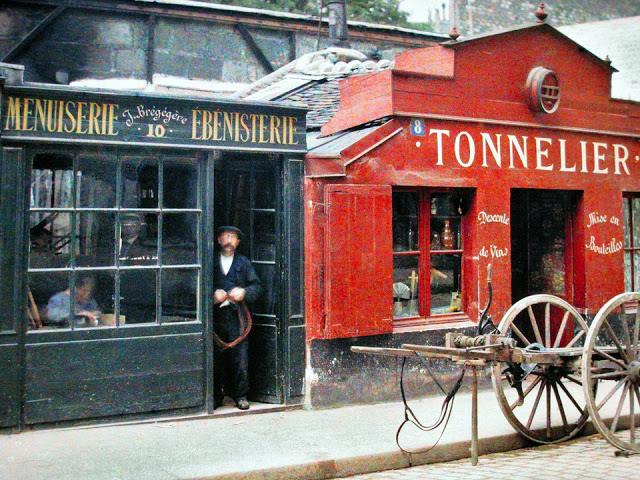

Not all of the photographs are of famous architectural monuments or nightlife destinations. Very many show ordinary street scenes, like those above, one depicting a number of bored French soldiers, presumably awaiting deployment.

The Paris of 1914 was a European capital in major transition, in more ways than one. “Modernity was the moving spirit,” writes Schofield; “It was the time of the machine. The city’s last horse-drawn omnibus made its way from Saint-Sulpice to La Villette in January 1913.”

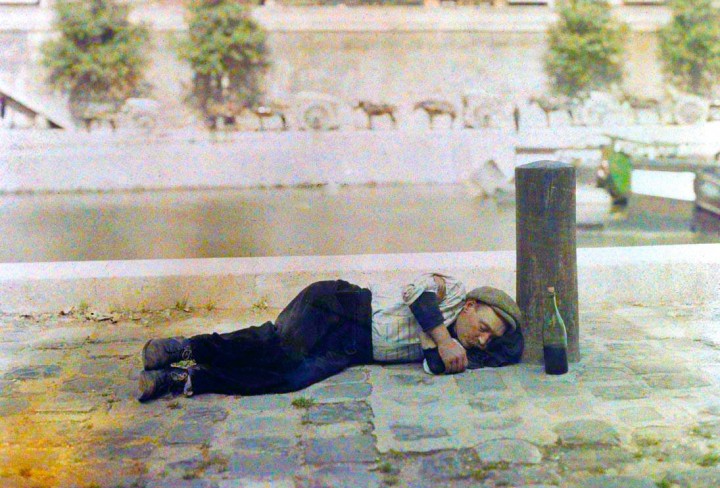

Schofield also points out that, like Gilded Age New York, “the public image of Paris was the creation of romantic capitalists. The reality for many was much more wretched… there were entire families living on the street, and decrepit, overcrowded housing with nonexistent sanitation.”

Modernity was leaving many behind, class conflict loomed in France as it erupted in Russia, even as the global catastrophe of World War I threatened French elites and proletariat alike, who both served and who both died at very high rates.

You can see many more of these astonishingly beautiful full-color photographs of 1914 Paris—at the end of La Belle Epoque—at Vintage Everyday and Messy N Chic.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

Paris Had a Moving Sidewalk in 1900, and a Thomas Edison Film Captured It in Action

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.