Rosa Parks wasn’t the first African American to publicly protest segregation in regional and local transportation systems in the modern civil rights era. Thirteen years before Ms. Parks refused to move for a white passenger, Bayard Rustin had a similar encounter. After purchasing a one-way ticket from Louisville to Nashville, Mr. Rustin was beaten and arrested for refusing to comply with the bus driver’s directive to sit in the back row. Mr. Rustin described this encounter and illustrated the power of nonviolent protest in one of his early essays “Nonviolence vs. Jim Crow” (1942), which we excerpt below:

Recently I was planning to go from Louisville to Nashville by bus. I bought my ticket, boarded the bus, and, instead of going to the back, I sat down in the second seat back. The driver saw me, got up, and came back to me.

“Hey you, you’re supposed to sit in the back seat.”

“Why?”

“Because that’s the law. N——s ride in back.”

I said, “My friend, I believe that this is an unjust law. If I were to sit in back I would be condoning injustice.”

Angry, but not knowing what to do, he got out and went into the station, but soon came out again, got into his seat, and started off.

This routine was gone through at each stop, but each time nothing came of it. Finally the driver, in desperation, must have phoned ahead, for about thirteen miles north of Nashville I heard sirens approaching. The bus came to an abrupt stop, and a police car and two motorcycles drew up beside us with a flourish. Four policemen got into the bus, consulted shortly with the driver, and came to my seat.

“Get up, you—N——!”

“Why?” I asked.

“Get up, you Black——!”

“I believe that I have a right to sit here,” I said quietly. “If I sit in the back of the bus I am depriving that child”—I pointed to a little white child of five or six—“of the knowledge that there is injustice here, which I believe it is his

right to know. It is my sincere conviction that the power of love in the world is the greatest power existing. If you have a greater power, my friend, you may move me.”

How much they understood of what I was trying to tell them I do not know. . . . Read more

Bayard Rustin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and raised by his grandparents, including a grandmother who was a Quaker and a charter member of the NAACP. He studied briefly at Wilberforce University and in 1937 moved to New York City, where he furthered his education at City College of New York. In 1938 he joined the Youth Communist League but severed his ties with that organization within a few years. In 1941 he accepted A. Philip Randolph’s invitation to assist in planning the first March on Washington, and later that year he became youth secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), the nation’s most influential pacifist organization. A decade before the quickening of the civil rights movement in the 1950s, Rustin and FOR, in conjunction with FOR’s civil rights offshoot, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), organized a series of Freedom Rides to give effect to a 1946 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that invalidated state-mandated segregation on interstate buses.

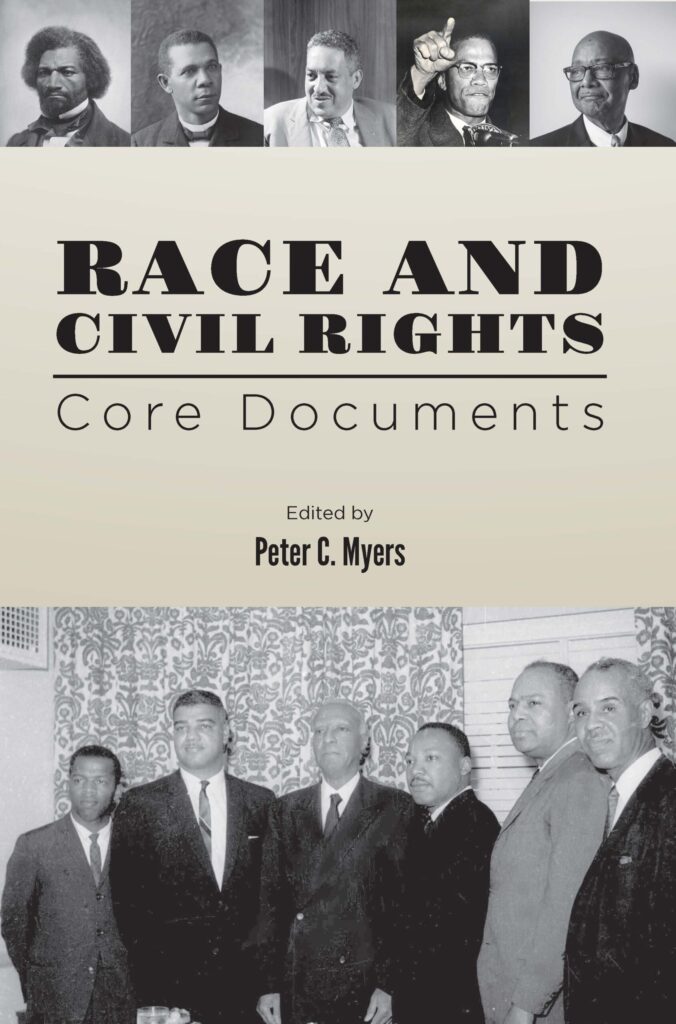

This document is excerpted from our CDC volume Race and Civil Rights, which contains classroom-ready primary sources, introductory essays and discussion questions. Download or purchase your copy today from our bookstore!