If you think of the Big Bang as an explosion, we can trace it back to a single point-of-origin. But what if it happened everywhere at once?

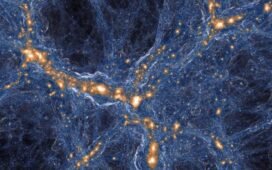

One of the most difficult concepts for anyone — even a professional astrophysicist — to wrap their minds around is the idea of the Big Bang and the expanding Universe. Off in the far-flung distance, at the limit of what even our most powerful telescopes can see, are galaxies speeding away from us so quickly that the light their stars emitted has been stretched to as much as twelve times their original wavelength. These stretched light waves are a consequence of the expanding Universe, and they are nearly, but not quite, identical for galaxies that we see in all directions in space.

Does that difference, and the fact that one direction has a slightly greater redshift for its objects than the opposite direction, tell us anything about where, all those billions of years ago, the Big Bang actually occurred? That’s what Finlay Matheson wants to know, asking:

“If you use redshift for light coming toward us and blueshift for receding light, can we tell where we are in the universe in relation to the origin of the Big Bang?”