(RNS) — The latest Catholic commotion is over the Vatican’s promotion of an accused abuser priest’s art.

Not long ago, the Vatican’s chief spokesman told 350 media professionals that Vatican media would still use art by Fr. Marko Ivan Rupnik, 69, currently under investigation for accusations of abusing women religious.

Paolo Ruffini, 67, prefect of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Communication, defended the official use of art by the accused serial rapist at the annual meeting of the Catholic Media Association in Atlanta. In Rupnik’s defense and by comparison, Ruffini asked the roomful of media professionals, “What about Caravaggio?”

What about him?

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was a philandering reprobate who produced stunning art. By an extraordinary use of light and dark, his paintings present a realistic view of what it means to be human, drawing the viewer into the deep human emotions he so realistically portrayed.

After killing a rich gangster, Ranuccio Tommasoni, in Rome — they fought over a gambling debt, or perhaps over a prostitute — Caravaggio remained on the run until he died in 1610. Some say he was traveling to accept a pardon for his sentence of death.

Caravaggio’s art influenced painters of the Baroque era and beyond, from Rubens to Rembrandt.

Lawyer Laura Sgro, from left, Gloria Branciani and Mirjam Kovac, former member of the Loyola community of sisters co-founded by the Rev. Marko Ivan Rupnik, during a news conference in Rome, Feb. 21, 2024. Gloria Branciani is one of the first women who accused Rupnik of spiritual, psychological and sexual abuse. (RNS photo/Claire Giangravè)

Rupnik is no Caravaggio.

Caravaggio’s paintings were commissioned for new churches and influential cardinals’ palaces. Rupnik’s mosaics adorn some 43 chapels or churches in Rome, and there are 231 works worldwide.

They are quite unusual. Some people find them ugly.

Rupnik’s mosaics invariably present the human person as long-faced and big-eyed. Dismissive of nature, they evoke the work of a primary school student enamored of bright colors and glitter.

Aside from Rupnik’s artistic departures from reality, his 20 or 30 accusers (so far) say he coerced them into sexual acts through spiritual and emotional abuse. Their stories are horrifying. One accuser said he abused multiple female members of the Loyola Community, which he founded in his native Slovenia, before decamping for Rome, where he founded the Centro Aletti art institute in the early 1990s.

Rupnik’s accusers say his sexual and spiritual abuse were essential to his creative processes.

The Society of Jesus — the Jesuit order Rupnik joined in 1973 — found the allegations credible and dismissed him in 2023 when he refused to abide by its restrictions. He promptly attached himself to a Slovenian diocese. He continues to produce and sell his work.

Some places are considering removing his work, but the Vatican’s Ruffini doesn’t think that’s a good idea. Even so, there is precedent for covering existing art. Mosaics commissioned in 1965 by Pope Paul VI in Rome’s major seminary are now hidden by a false wall with floor-to-ceiling Rupnik depictions of Biblical scenes in bright reds, oranges and yellows. That would be easy to take down.

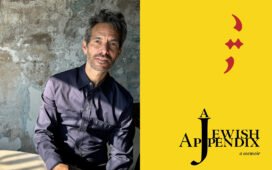

Fr. Marko Ivan Rupnik in a video from 2022. (Video screen grab)

But the question was not so much about removing Rupnik’s mosaics as it was about his art’s continued promotion in Vatican materials. The Vatican maintains several Rupnik images on its websites, and Ruffini told the Atlanta assembly he had no intention of taking them down, saying removing art would not show “closeness” to Rupnik’s victims.

What about the other victims, especially the female victims, of sexual and spiritual abuse by clerics around the world?