.pod-stream-buttons {

display: flex;

justify-content: center;

margin-bottom: 1.5rem;

}

.stream-button {

flex: 1 1;

margin-right: 0.5rem;

}

.stream-button:last-child {

margin-right: 0;

}

.stream-button a {

display: flex;

}

.stream-button object, .stream-button img {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

.wp-remixd-voice-wrapper {

display: none !important;

}

(RNS) — Rabbi Yitz Greenberg is my oldest rabbi friend.

First, this modern Orthodox rabbi was one of the first rabbis to really touch my life and to engage me in what my Protestant colleagues would call “formation.”

Rabbi Yitz Greenberg was a congregational rabbi in Riverdale, New York, the founder of the Jewish studies program at City College of New York and the creator of the Center for Learning and Leadership (CLAL), a think tank for Jewish pluralism and intra-Jewish conversation.

I first met Rabbi Greenberg and his wife, Blu Greenberg, the major Jewish feminist leader, when he engaged me to work with a bunch of modern Orthodox teenagers on a CLAL retreat.

That encounter with Rabbi Greenberg, whom I would come to know as Yitz or Rabbi Yitz, changed my perception of Orthodox Jews and Orthodox Judaism. It made me more open to seeing the Jews as a unified people and not just a discrete collection of ideologies.

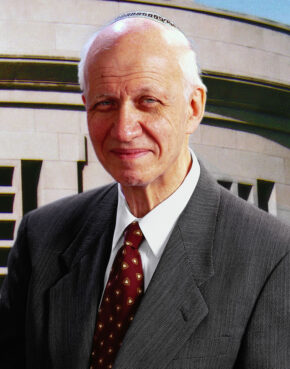

Rabbi Irving ‘Yitz’ Greenberg. (Courtesy photo)

Yes: This Orthodox rabbi helped shape the world view of this Reform rabbi. His vision of an observant Judaism that was open to the world, and freely encountered the world, moved me — so much so, that decades later, I would become a regular participant in the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, founded by Rabbi Greenberg’s colleague, the late Rabbi David Hartman — also an Orthodox rabbi and, like Yitz, also a rebel.

The second way in which Rav Yitz is my oldest friend in the rabbinate: He is 91 years old, and he has just published his magnum opus, his master work, the culmination of everything that he has taught for so long — “The Triumph of Life: A Narrative Theology of Judaism.”

This is the book that Yitz’s students — and frankly, the Jewish world — have been waiting for for more than a half century.

Yitz’s central idea: Judaism is a religion of life, that centers on life, in which every commandment affirms life and moves the human being toward higher affirmations of life and, ultimately, toward God.

The essence of the commandments is for us to live through them. When there is a choice between life/health and a religious duty, the Jew must set aside almost any religious duty in order to save life.

Yitz writes:

God wants the forces of order and life to win out. God asks humans to live in such a way that in their actions, they join in on the side of order and against chaos, on the side of life and against nonlife and death, on the side of increasing quality of life and against dumbing it down.

The meaning of the covenant between God and the Jewish people is that we might repair the world — tikkun olam — to perfect the world and to bring it closer to God’s ultimate vision of human perfection. At every stage of Jewish life, we are called upon to see our actions, and the arenas in which we play them out, as microcosms of that perfect world.

The Torah works with microcosms, inner circles that may be expanded.

The (ancient) Temple is the microcosm for space; Shabbat is the inner circle for time; the Jewish people is the inner circle for humanity.

In time the inner circles will expand and include all those in the outer circle. Thus holy space will encompass Jerusalem, then Israel, and eventually the whole world.

Shabbat will grow until the whole week is the zone of full life.

The holy people will expand until all of humanity are holy people.

For Yitz, what teaching forms the moral core of Judaism? “The great principle underlying the ethic of the Torah is that every human being — regardless of gender, race, skin color, nationality, or religion — is created in the image of God, and endowed accordingly with three fundamental dignities: infinite value, equality, and uniqueness.”

Infinite value and infinite worth. In the movie “The Monuments Men,” a team goes into Europe during World War II to find and save valuable pieces of art that the Nazis had stolen and threatened to destroy. I liked the movie; I greatly disliked the story. People worked admirably to save works of art; they labored far less admirably to save the real works of art — God’s children, God’s creations.

In Yitz’s words:

What is the value of an image of a human being?—that is, of a work of art created by a classic artist? Multiple Picassos have sold for over $100 million … In 1990 the world record for a painting at that time was set when one by Van Gogh — itself literally an image of a man, the Portrait of Dr. Gachet — was sold for $82.5 million to a Japanese insurance company.

This is precisely what formed Rav Yitz’s lifelong involvement in Holocaust remembrance. (He was one of the founders of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.) The Nazis incinerated Jewish children alive in order to economize on the cost of gas. The Holocaust was a unique assault on the divine image. Therefore, anything and everything that we can do to uphold the divine image is sacred work.

Upholding the divine image — that is our task — even as the divine seems to fade. In one of his most profound moves, Rabbi Yitz demarcates three eras in Jewish history — the biblical, the rabbinic and the modern. In each era, the presence of God changes. God is no longer manifest, as God was in biblical times; God withdraws into the divine self to allow greater human activism.

His words:

God is now totally hidden in natural laws and material processes. Today, God makes more miracles than ever, but only through human agency — our unlocking the miraculous powers in physical and biological matter that only we can exercise by understanding and utilizing nature’s laws.

Once upon a time, people lived lives of faith, sometimes interrupted by moments of doubt. Today, people live lives of doubt, sometimes interrupted by moments of faith.

“The Triumph of Life” is simply that — a triumph of the Jewish mind and spirit. It is a remarkable tribute to the life work of one of contemporary Judaism’s most treasured and cherished voices. That it emerges when he is 91 years old is itself a blessing — first, that he had the blessing to see his work come to light, and second, that, in the words of Deuteronomy in describing the elderly Moses, “his eye is undimmed” and his spirit as strong today as it was decades ago.

“The Triumph of Life: A Narrative Theology of Judaism” by Rabbi Irving Greenberg. (Courtesy image)

More than that: My friendship with Yitz and Blu has enriched my life immeasurably. Their hospitality to me, with the accompanying conversations about the challenges of modernity, and how our respective Judaisms confront those challenges, have become the true highlight of my July sojourns in Jerusalem.

Years ago, he said something that has always stayed with me — the job description of the Jews, in three Ps:

The Jews are pedagogues — teaching the idea of the infinite value, equality and uniqueness of every human being — even and especially in times and places when this idea would have been considered absurd.

The Jews are paradigms — a working model to show how we can perfect the world. A working model is not perfect, but nevertheless, the Jews can still be a model.

The Jews are partners — working with those of other faiths and even no faith in perfecting the world. It is only now, in a time of increased religious dialogue, that such a partnership is even thinkable.

One last thing.

It is not only that Rabbi Yitz Greenberg, at 91, is my oldest friend in the rabbinate (or anywhere else, for that matter).

It is far more than that.

Rabbi Yitz Greenberg is the last of his generation of Jewish thinkers.

I think of those from whom we have learned and who have died: Eugene Borowitz, Leonard “Leibel” Fein, David Hartman, Jacob Neusner, Richard Rubenstein, Harold Schulweis, Steven Schwarzchild, Elie Wiesel, Michael Wyschogrod. The list goes on and on.

No women? Actually, there are two — and both of them are still quite alive. There is Cynthia Ozick, 96 years old — novelist, literary critic and Jewish thinker. And there is, of course, Blu Greenberg, whose vision of Jewish feminism created and nurtured a generation of Jewish feminist thinkers.

But, that list of thinkers … All of them, born between 1924 and 1934. All of them, now studying together and arguing loudly and vociferously at a table in the world to come.

Only Yitz is still here.

Let’s keep it that way. Yitz Greenberg is the living witness to the words of the Psalmist: Do not cast us off into old age.

Until 120. Please.