By Lara Westwood, Librarian

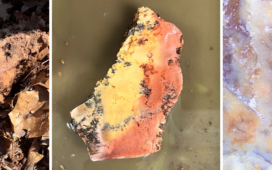

Each year, the nation’s lighthouses are celebrated on August 7th. The holiday commemorates the date “An Act for the Establishment and support of Lighthouses, Beacons, Buoys, and Public Piers” was signed in 1789. The Cape Henry lighthouse in Virginia was the first lighthouse commissioned by the new congressional act. Construction on the lighthouse was completed in 1792 and guided ships through the treacherous waters at the opening of the Chesapeake Bay until 1881 when a new lighthouse was built adjacent to it. The lighthouse was constructed of Aquia sandstone near the first landing site of the English colonizers at Jamestown. This project kicked off a boom of lighthouse construction along the banks of the bay and its tributaries. Nearly 40 of Maryland’s historic lighthouses have been documented in the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties (MIHP), including the remaining structures built during these early building efforts.

Planning for Maryland’s first lighthouses began in 1820. Sites near Baltimore on Bodkin Island, North Point, and Sparrows Point on the Patapsco River were selected to light the Chesapeake Bay to mark shoals that proved obstacles in navigation. Completed in 1822, the Bodkin Island lighthouse was the first lighthouse in Maryland. Thomas Evans and William Coppeck were initially hired to build the lighthouse, but they were fired after it was discovered that they were cutting corners in construction. Revolutionary-War veteran John Donahoo, who became Maryland’s most prolific lighthouse builder, was brought on to complete the project. A commercial fisherman by trade, it appears that Donahoo did not have any formal training in engineering or architecture. The tower rose thirty-five feet over the river with a small stone dwelling next door to house the keeper. The Seven-Foot Knoll lighthouse (B-4222) replaced it in 1856 when it was decided a screwpile lighthouse situated in the river would better serve the area, although the Bodkin Island lighthouse stood until 1914.

Donahoo built at least 12 lighthouses in Maryland between 1825 and 1853, including the oldest extant lighthouse in Maryland at Pooles Island (HA-1846), erected in 1825 and now a part of Aberdeen Proving Ground. The 40-foot tower lit the mouths of the Bush and Gunpowder Rivers in Harford County, and the site included a barn, boathouse, and keeper’s residence. In its prime, Pooles Island was an idyllic locale as it boasted an orchard of peach trees planted by a private owner after the War of 1812 and was a popular spot for bathing. The island even hosted a prize fight between Tom Hyer and James “Yankee” Sullivan in 1849. Boxing was illegal at the time, and the location was chosen due to its out-of-the-way location. The lighthouse was automated in 1917 and was in service until 1939. The structure is currently not accessible to the public as the United States Army used the site for bombing and shelling practice, littering the island with unexploded ordnance. Donahoo’s first attempt at building a lighthouse at Thomas Point near Annapolis was a failure; the ground chosen for the structure turned out to be unsuitable and prone to erosion, so the tower quickly became unstable. It was rebuilt on higher ground in 1838 and was later replaced by the screw pile lighthouse that stands today (AA-358). Of the other lighthouses constructed by Donahoo, those that still stand today include Concord Point/Havre de Grace (HA-251), Cove Point (CT-65), Point Lookout (SM-271), Turkey Point (CE-195), Piney Point (SM-270), and Fishing Battery Island (HA-1845).

Lighting and building technologies for lighthouses were ever improving. To provide illumination, a lighthouse required lanterns, lenses, and lamps. In the early days, lamps were lit with whale oil or lard. Sperm whale oil was preferred as it burned cleaner, but was tremendously costly. Oil lamps were eventually switched to kerosene, which was cheaper to procure. Lenses had to be constantly cleaned to remove the soot to keep the light shining bright, but over time the reflective silver coating wore off making the light less effective. By the 1850s, the United States Lighthouse Board replaced the old lenses with ones invented by Frenchman Augustin-Jean Fresnel (“Fresnel lenses”), which reflected light more effectively and reduced the amount of fuel used by the lamps. Electrification also greatly changed how lighthouses were maintained. By World War I, most lighthouses had automatic, electric lamps with an alarm system to alert the lighthouse keeper of burned-out lamps. Automatic radio beacons eventually were installed making the system completely automated.

Screw pile lighthouse completely revolutionized lighthouse building on the Chesapeake Bay. Beacons were needed out in the waters of the bay, but eroding land and its soft floor meant that the traditional tower-style lighthouses could not be built. Over 40 were built between 1854 and 1908, and those that remain standing today include Thomas Point Shoals Light Station, Drum Point (CT-68), and Seven-Foot Knoll. A screw pile lighthouse was suspended above the water on cast-iron stilts. The legs screwed into the bottom making it suitable for building on muddy or sandy ground. This style of lighthouse could be built more quickly than the traditional stone towers, and the keeper’s cottage could be prefabricated off-site. In 1863, a depot on Lazaretto Point in Baltimore was opened to build the lighthouse superstructures and operated until 1958 when the land was sold.

Situated in the water and exposed to the elements, lighthouses were threatened by storms and ice in particular. Several were actually carried off by ice floes and had to be abandoned by their keepers. Later lighthouses were built on caissons as opposed to screw piles, which proved to be much sturdier. Examples of lighthouses built on caissons that still remain are the Baltimore Lighthouse (AA-945), Bloody Point Bar Light (QA-297), Hooper Strait (D-644), Craighill Channel Lower Range Front Light (B-1551), Point No Point Light Station (SM-272), Sandy Point Shoal Light (AA-166), Sharps Island Light (T-477), and Solomons Lump Light Station (S-425). The Craighill Channel light near Baltimore is the oldest among the caisson lighthouses in Maryland. Built in 1873, the lighthouse was manned until 1964 when it was completely automated.

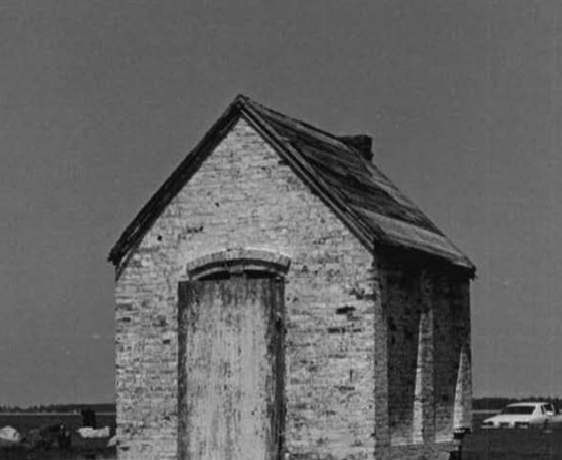

Constant maintenance of the light and grounds before the days of automation meant that lighthouse keepers often brought their families to live at the lighthouse. The keeper was expected to operate the light at appointed times–sometimes 24 hours a day during bad weather–and assist in the event of emergencies. Most lighthouses were built with adjacent or attached living quarters, which ranged from small cottages to sizable houses suitable for large families. In the case of screw piles, the house would be built suspended above the water below the light. The Drum Point lighthouse on the Patuxent River was noted for having a dining room, which was an unusual feature on screw pile lighthouses. Lighthouse keeper James Loch Weems and his wife Alice were noted entertainers and required a space to do so in their home at Drum Point. Families of keepers were eventually barred from living on screw piles due to risks related to severe weather and ice. The grounds of inland lighthouses were used to cultivate crops and keep livestock to maintain the residents. Few associated structures remain, but some have been documented in the MIHP. A smokehouse (SM-513), likely built in the late 1870s, survives on the grounds of the Point Lookout lighthouse. The building was later used as a stable and corn storage.

Often a family member would take over the position when a lighthouse keeper died in or retired from service. This included a number of women who were the widows or daughters of previous keepers. In explaining his decision to allow women to take the position, Stephen Pleasonton, appointed to run the Lighthouse Establishment in 1820, stated, “So necessary is it that the Lights should be in the hands of experienced keepers that I have, in order to effect that object as far as possible, recommended on the death of a keeper that his widow, if steady and respectable should be appointed to succeed him, and in this way some thirty odd widows have been appointed.” Female lighthouse keepers received the same pay as men and performed the same duties. Maryland’s first female lighthouse keeper was Araminta Gray who took over duties at the Bodkin Island lighthouse after her husband, John Gray, died in service in 1823. She was hired under the condition she would find a man to be appointed officially while she continued to perform the keeper duties. While her nephew initially took the role, Gray resigned the post after her new husband, a non-citizen, was denied the position. Her tenure, though, would set a precedent of women keepers, with 19 women on record across the Chesapeake Bay. Ann Davis took over the Point Lookout lighthouse in 1830 after her father passed away within three months of being hired. In inspection reports, Davis was commended for keeping a particularly clean and neat light. Fanny May Salter was the last female civilian lighthouse keeper employed by the United States Coast Guard. She lived and worked at Turkey Point near Havre de Grace from 1922 until 1947. She took over the position when her husband, C. W. “Harry” Salter, died in 1925. After she retired at age 65, Fanny May lived a short distance away with a view of the light she tended for so long.

Most lighthouses had been automated by the 1960s and the role of lighthouse keeper was phased out. The United Coast Guard took over maintenance of the active lighthouses and many of the others were decommissioned. Without the constant care of the keepers, many of the lighthouses fell into disrepair. While some were razed or allowed to erode into the water, others were sold into private hands. Disturbed at the state of these icons of the Chesapeake Bay, preservationists rallied to their cause and were able to save several lighthouses from total destruction. The Maryland Historical Trust holds 10 protective easements on lighthouses across the bay. Several were moved to safer harbor, including the Seven Foot Knoll and Drum Point lighthouses. The lighthouses that still dot the Chesapeake Bay remain as reminders of Maryland’s maritime history.

References and further reading:

“Bodkin Point Lighthouse.” Chesapeake Chapter U.S.L.H.S., April 7, 2013.

Browning, Robert. “Lighthouse Evolution & Typology.” U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office , n.d.

“Chesapeake History: Pooles Island .” PropTalk, n.d.

Clifford, Mary Louise, and J. Candace Clifford. Women Who Kept the Lights: An Illustrated History of Female Lighthouse Keepers. Williamsburg, Va: Cypress Communications, 1993.

“Craighill Channel Lower Range Front Lighthouse.” Chesapeake Chapter U.S.L.H.S., April 12, 2013.

Cronin, William B. The Disappearing Islands of the Chesapeake. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press in association with the Calvert Marine Museum, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, Mariner’s Museum, and the Maryland Historical Society, 2005.

De Gast, Robert. The Lighthouses of the Chesapeake. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

De Wire, Elinor. Lighthouses of the Mid-Atlantic Coast: Your Guide to the Lighthouses of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia. Pictorial Discovery Guide. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press, 2002.

Gendell, David. Thomas Point Shoal Lighthouse A Chesapeake Bay Icon. Landmarks. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing Inc., 2020.

Holland, F. Ross. Maryland Lighthouses of the Chesapeake Bay. Crownsville, Md. : Colton’s Point, Md: Maryland Historical Trust Press ; Friends of St. Clement’s Island Museum, 1997.

Hornberger, Patrick, and Linda Turbyville. Forgotten Beacons: The Lost Lighthouses of the Chesapeake Bay. Annapolis: Eastwind Pub., 1997.

Lloyd, A. Parlett. The Chesapeake illustrated. [Baltimore, A. P. Lloyd, 1879] Pdf.

Digital Exhibits. “Lighting America’s Beacons: U.S. Lighthouses Under the Department of Commerce.” United States Department of Commerce Commerce Research Library, n.d.

“National Lighthouse Day – August 7th.” American Lighthouse Foundation, n.d.

Randall, Kayla. “The Story Behind the Chesapeake’s Feminist Lighthouse.” Washingtonian, The Washingtonian, 2017.

Staff, S. I. “‘Run, Sullivan! Run!’” Sports Illustrated Vault . Sports Illustrated, September 30, 1974.

Turbyville, Linda. Bay Beacons: Lighthouses of the Chesapeake Bay. 1st ed. Annapolis: Eastwind, 1995.

“Types of Lights.” Chesapeake Chapter U.S.L.H.S., n.d.

United States. Historic Lighthouse Preservation Handbook. [Washington, D.C.]: National Park Service, 1997.

United States Coast Guard. “Fannie May Salter, Lighthouse Keeper,” n.d.

United States Coast Guard. “Lazaretto Point Lighthouse,” n.d.

Vojtech, Pat. Lighting the Bay: Tales of Chesapeake Lighthouses. 1st ed. Centreville, Md: Tidewater Publishers, 1996.

Women Lighthouse Keepers. “Breaking the Barrier: Women Lighthouse Keepers and Other Female Employees of the U.S. Lighthouse Board/Service.” United States Coast Guard, n.d.