Yves here. Your humble blogger has from time to time referred to the work of Jonathan Haidt, including on the effectiveness of protests (he says they work but often not directly or quickly) and more famously (or notoriously, depending on your point of view) on anti-depressants.

Perhaps readers will disagree, but as far as I can tell, the mental health industry does not have very good treatments for anxiety (ex perhaps meditation and psychedelics, which I doubt are mainstream) so societal fostering of anxiety in the young is really not a very good idea.

KLG’s intro:

This is a review-discussion of Jonathan Haidt’s latest book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, that places it in current context regarding my experience in teaching Gen Z medical students and a historical context related to the Marxian concept of self-realization as described by Jon Elster. My thesis is that the near total immersion of some students in social media has indeed made them fragile and reluctant to take charge of their education as aspiring physicians. The connection with the work of Elster is that social media also engender a passive consumer mentality in children and that this often carries over into adulthood and leads to less than optimum outcomes for these targets, while the various social media platforms produce billionaires.

(I can imagine how the usual suspects are reacting to this book, but to me the conclusions are mostly unassailable.)

By KLG, who has held research and academic positions in three US medical schools since 1995 and is currently Professor of Biochemistry and Associate Dean. He has performed and directed research on protein structure, function, and evolution; cell adhesion and motility; the mechanism of viral fusion proteins; and assembly of the vertebrate heart. He has served on national review panels of both public and private funding agencies, and his research and that of his students has been funded by the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and National Institutes of Health

The social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has become something of a lightning rod with his recent work. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, written with Greg Lukianoff, was praised and panned by the usual suspects. That the title echoes The Closing of the American Mind, which made a very large splash for Alan Bloom in its day, undoubtedly conditioned various reactions. Haidt’s current book The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illnessis likely to have similar effects on the same people. I avoided reading anything about this book before reading it, because I thought I might want to write about it. I have now read it.

Why do I view The Anxious Generation as worthy of discussion? My day job since 1998 has including teaching graduate students in the biomedical sciences and medical students during their first two (preclinical) years of medical school. During that time things have changed. I don’t generally view the classification of people as members of “generations” as particularly useful, but it inevitable and must be dealt with. I am a Baby Boomer, and when complaints about our current parlous state are thrown my way by default this can be irritating. Yes, I am by accident of timing a member of the same generation that includes Bill and Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, Donald Trump, Bill Kristol and Niall Ferguson. What we have in common ends there. Each member of Gen Z is also unique but like Baby Boomers, they too have been shaped by common experiences.

Older generations have been lamenting the deficiencies of their successors at least since Socrates, and most of these complaints have been ridiculous for these 2500 years. Yes, people do “make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already (1852).” [1] Political economy, culture, and society, not necessary in that order except for the vulgarians – left and right – in our midst, condition who we are, what we can be, and what we can do. Those who point this out frequently get on the nerves of those “in charge” or our politics and our educational institutions. Professor Haidt has become very good at this.

The Anxious Generation is a rapid but not breezy read. The coming quibbles, if not outright attacks, are easy to imagine. I am not competent to evaluate all the evidence concerning the effects of the “Great Rewiring” of mental health, especially concerning members of Generation Z – the Smartphone Generation – but the results considered and evaluated in the book make eminently good sense. Whether each psychological study can be or will be “replicated” is not a useful question or valid criticism. We have considered the replication crisis before. Specific examples are often a consequence of faulty statistical arguments or require population studies to show a degree of rigor impossible outside a chemistry or physics laboratory. This includes cell biology and physiology, cancer biology, and biochemistry, by the way: The more complex the system, the more variability to be expected. Psychology is a legitimate scientific discipline even if the outcomes of psychological research are not determined by the physical world!

Still, I often hear my colleagues in the so-called “hard sciences” say that psychology is “not a science” so it can be safely ignored. In my corner of that world, these are the same scientists who have gone all-in on the amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and statins as the cure of coronary heart disease, to no substantial effect for the past 30 years. The finding that 10-20-30% of a certain very large number of young people of Gen Z are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety disorders than their predecessors is much more believable than “amyloid plaques cause AD” (found in the NC Links of January 30, 2024).

Yes, the DSM has undergone “mission creep” over the years due to the inevitable influence of Big Pharma and Biomedicine, but the problems covered in The Anxious Generation are nevertheless real. I have seen them at first-hand. I am skating close to the edge of Horowitz’s Law [2] here, but my experience is not limited to me. The coddled and anxious students described by Lukianoff and Haidt do exist. And it is a strange thing. For example, medical students can get a test-taking accommodation because they have “test anxiety.” I’ll leave that evidence of hyper-fragility right there, except to remind these students that such accommodation will not be granted when they take their licensing examinations required to graduate from medical school and then enter and leave residency to become an independent physician.

But first, what is in the book? The Anxious Generation shows convincingly what children must do in childhood if they are to become well-adjusted, functional human beings. Absorption into the virtual world of a smart (sic) phone, which was introduced when the youngest children of Gen Z were ~10 years old, is not on the list:

As the transition from play-based childhood proceeded, many children and adolescents were perfectly happy to stay indoors and play online, but in the process they lost exposure to the kinds of challenging physical and social experiences that all young mammals need to develop basic competencies, overcome innate childhood fears, and prepare to rely less on their parents. Virtual interactions with peers do not fully compensate for these experiential losses. Moreover…(they wandered) increasingly through adult spaces, consuming adult content, and interacting with adults in ways that were often harmful…(and)…even while parents worked to eliminate risk and freedom in the real world…(they often unknowingly) granted full independence in the virtual world

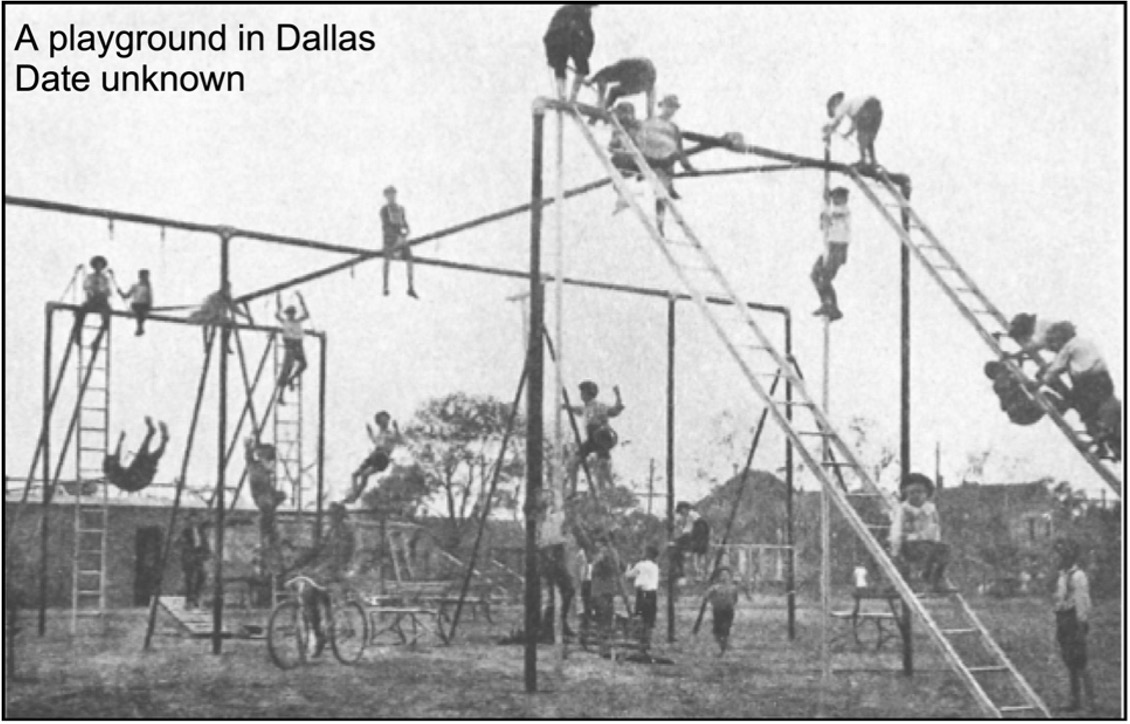

This brings us to the “safetyism” that has become the “standard of care” for all children since the 1980’s. Those of us of a certain age remember playgrounds that were marginally hazardous, especially compared to those of today, although I never encountered one that looked quite like this:

A bit more “coddling” may have been more in order than this course fit for a Navy SEAL, but these children (all boys as far as I can tell, alas) learned what they could do without hurting themselves. They were definitely in their discovery mode (for approaching opportunities) rather than in their defend mode (for defending against threats). They naturally became anti-fragile in this environment. And free play is the key [3]. Virtual, screen-based experiences are just not the same, nor will they ever be sufficient for proper physical, mental, social, and cultural development.

The often-ignored distinction between digital technology and social media is also a key point of The Anxious Generation. Although I much prefer to read books and journals in analog, most of my work is digital in one form of the other, including typing this on a MacBook Pro using Microsoft Word. Much to my disappointment, local newspapers are not coming back along with a reasonable news cycle. In my view this is a major contributor to our current distemper, but I digress. Haidt’s Four Harms of Social Media are convincing:

- Social Deprivation: Teens who spend more time on social media than with friends are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression, while teens who spend more time in groups have better mental health, on average. Synchronous contact with friends is superior to asynchronous interactions with “friends” and “followers.”

- Sleep Deprivation: Screen-related decline of sleep probably contributes to the increase in adolescent mental distress since the introduction of the smartphone. [4]

- Attention Fragmentation: Contrary to common chatter, and to the disappointment of students, multitasking is not a thing. We can shift attention back and forth between tasks while wasting a lot of it on each shift. Perhaps not unrelated, it is a rare medical student these days who can answer a question in a tutorial group without consulting a mobile device of some kind – smartphone, tablet, laptop.

- Addiction: “The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation.” Dopamine release is pleasurable, but it does not trigger a feeling of satisfaction. It makes you want more likes, for example, but it is clear that the law of diminishing returns applies. The difference between pre- and post-smartphone is that earlier digital devices were not portable for facile use everywhere, all the time, including when we should be sleeping. This applies to adolescents of all ages.

The trap is that smartphones deliver social media on demand. This harms girls and boys in different ways. For example, girls are more affected by comparisons with others and social media have been shown to cause rather than correlate with anxiety and depression (no doubt to be disputed). Boys are more likely to suffer from “failure to launch” as they retreat into their virtual, asynchronous world of communities “populated by known individuals” and anomie described by Émile Durkheim as normlessness – an absence of stable and widely shared norms and rules:

If this [binding social order] dissolves, if we no longer feel it in existence and action about and above us, whatever is social in us is deprived of all objective foundation. All that remains is an artificial combination of illusory images, a phantasmagoria vanishing at the least reflection; that is, nothing which can be a goal for our action.

This brings me to an older explanation of our current situation that makes perfect sense to me. Jon Elster published an article in Social Philosophy & Policy in 1986, “Self-realization in Work and Politics: The Marxist Conception of the Good Life” (paywall but a summary is at the link) that has explained much to me in the intervening years and may have a lesson for today’s hyperconnected virtual world of social media. [5] According to Elster:

(Among the) arguments in support of capitalism…the best life for an individual is one of consumption…(which is)…valued because it promotes happiness or welfare, which is the ultimate good…I shall argue that at the center of Marxism is a specific conception of the good life as one of active self-realization rather than passive consumption…A list of some activities that can lend themselves to self-realization: playing tennis, playing piano, playing chess, making a table…writing a book, discussing in a political assembly, bargaining with an employer, trying to prove a mathematical theorem, working a lathe…fighting a battle, doing embroidery, organizing a political campaign, building a boat.

Of course, “self-realization through political participation is self-defeating if the political system is not oriented toward substantive decision making,” a morass into which we sink deeper by the day. But the point is that to be healthy and happy human beings, it essential that we work at our own self-realization. [6] It really does not matter what we do, but self-realization is not something that can be bought, or bought and then passively absorbed in a virtual world.

From Elster, first-time consumption has a large utility (U), using the terminology of the economist. But after many repetitions, U decreases as the law of diminishing terms kicks in and more consumption is required to reach the unattainable original value of U. Addiction can present in many forms. On the other hand, when expending effort instead of money (and wasted time), U is low at first but increases with each succeeding attempt to master your goal: tennis or chess, reading the complete works of Thomas Hardy, writing that book, building a robust local community where you live. And if you find you are unable to play tennis as well as you like, there is always pickleball. We have been conditioned to consume (highly recommended) for more than a hundred years, but consumption is a dead end that requires the development of nothing particularly human, not to mention the death of a livable world.

So, what does this have to do with The Anxious Generation? While not paying attention, and not understanding that we and our children are the product of social media instead of their clients or customers, we have as a polity and society become passive consumers who often succumb to addiction to the dopamine hits the big platforms have become so adept at pushing. Spending three hours watching videos of very accomplished dancers can be entertaining up to a point. But at some level we all recognize that it would be healthier – mentally, physically and socially – to learn to dance. But that option may not even exist. Which is exactly how Big Social Media want it.

The Anxious Generation concludes with solutions, most of them well considered. Governments could raise the “age of consent” for social media to 16 instead of 13, which the current standard (not that it is followed by Big Social Media or the law). This is unlikely given the existence of K Street and a Congress that spends four hours a day dialing for dollars. Phone-free schools are doable, however, and they make a big difference in student outcomes, social and educational. Parents who wail that “I must be able to contact my child at any time” are still free to call the Principal’s Office. Personally, I cannot ever remember my mother (or father) calling the school for me, but the school called my mother on several regrettable occasions. Free play must be reinstituted as a normal school activity. This will keep the teachers sane and allow the children to teach each other how to solve their own problems without the intercession of an adult.

Finally, I realize that my favorable responses to The Anxious Generation and The Coddling of the American Mind may well be due to confirmation bias. But I have seen remarkable changes in medical student behavior over the past 16 years, especially as Gen Z has gotten to medical school. Challenging them to do better can be, well, a challenge. Students are still academically prepared on paper, but they are more fragile and much “harder to please.” [7] Attention spans are short, and as mentioned previously, it is the rare medical student who can answer a question without first looking at his or her screen. They have adapted well to the current style but this may not end well, even as doctors type into the computer on the stand next to the bed more than they listen to their patients lying in the hospital bed or sitting in their examination room. So, who knows?

Still, many of us have begun to tell the truth, carefully, as we see it to students: (1) You must take responsibility for your performance, whether the tutor uses your preferred style or not. (2) Everyone has imposter syndrome to some extent, but you would not have gotten into medical school if you were not qualified to do the work. (3) And the work is much harder than downloading the assigned chapter from a free-to-you electronic textbook as a pdf and then looking it over – it is a long way from the screen in front of you to mastering the knowledge and skills required of a physician. Based on my reading, and it is an occupational hazard to sometimes read the literature of pedagogy, this is true at every educational level.

I also have the sneaking suspicion that early, unthinking, largely involuntary immersion in the virtual world of social media is responsible for failures in metacognition – knowing and understanding what you do not know – we have seen in too many students recently. Passive consumption of virtual noise rather than active realization of a tangible goal leads to bad outcomes. Confirmation bias or not, that would be a good research topic. For someone else.

Finally, as one Southern Agrarian wrote nearly a hundred years ago in response to radio (paraphrase): “It is the better path to take the fiddle down from the mantle and play it.” Good advice still.

Notes

[1] The longer version is here: Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language.

[2] Revealed to me by Dr. Joel Horowitz when he taught my Introductory Sociology class: Never generalize based on your own necessarily limited personal experience. Several students may have been offended by a teacher unlike anyone in their previous experience, but no one complained to the Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences. The one student who brought his Bible to class to refute Horowitz comes to mind. He was anything but fragile, however. Nor did he consider himself to be in an unsafe environment in that lecture room with ~40 other students. The reaction to those of us who came to learn rather than make a “C” (believe it or not, that happened way back then) in a required social science class was, “Wow, Horowitz is great, even if he does say these outrageous things every day!” Yes, five days a week in the much superior academic quarter system: You can endure anything or anyone for 10 weeks.

[3] But parents who allow their children to be free-range kids are likely to be reported to the Department of Family and Children’s Services for child neglect. The deleterious social and cultural changes that in the 1980s and 1990s led to the death of free play are covered extensively in The Anxious Generation. But then there is stupid. When I think back to some of my escapades, a shudder comes over me, led by memories of building a raft using two large innertubes, a hand drill, some rope, and a sheet of plywood and then “sailing” our vessel with a slightly older friend into a river with strong tidal currents less than a half-mile from an oceangoing shipping terminal. What was most interesting in retrospect is that men working at an adjacent industrial site waved to us, probably remarking to one another about “the good times those kids are having on a summer day.” No one called the police or the Coast Guard. The latter may have admired our “ingenuity,” but the lack of life preservers would have been a most serious offense. Still, we did not drown or get run over by a ship that could not see us and learned what not to do when back on terra firma.

[4] As an aside, in our experience as parents, my wife and I noticed early on that the symptoms of occasional sleep deprivation in our children (N = 2, but sometimes N = 1 is enough) are virtually identical to those of ADHD. Contemporaries of our children whose parents always seemed to say “our kids don’t need that much sleep” were apparently unable to recognize the symptoms in their own children.

[5] Elster’s argument here is taken largely from Making Sense of Marx, which is one of the foundational works of the Analytical Marxists who followed G.A. Cohen and his Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defense (1978).

[6] This can be done at some level for most people, whatever one’s personal circumstances. The fatal flaw of Liberalism is that good Liberals fail to recognize their own fortunate choice of parents, place, and time. That self-realization is impossible for so many is a failure of the Liberal imagination as much as a failure of political economy.

[7] “Student satisfaction” is high on the list of accreditation issues for every medical school. This is measured in pre-matriculation questionnaires, surveys after each year of medical school, and a graduation questionnaire. One of the primary reasons for administrative hypertrophy is that people have to deal seriously with this stuff. One sometimes wonders if the accreditation body understands that the satisfied student is the one who is pushed and then passes board exams with ease, rather that the student who was coddled and faces a looming uncertainty with absolute dread. This is not to excuse the proverbial Old School, however, for their legendary arrogance and uncaring behavior in the classroom and the clinic.