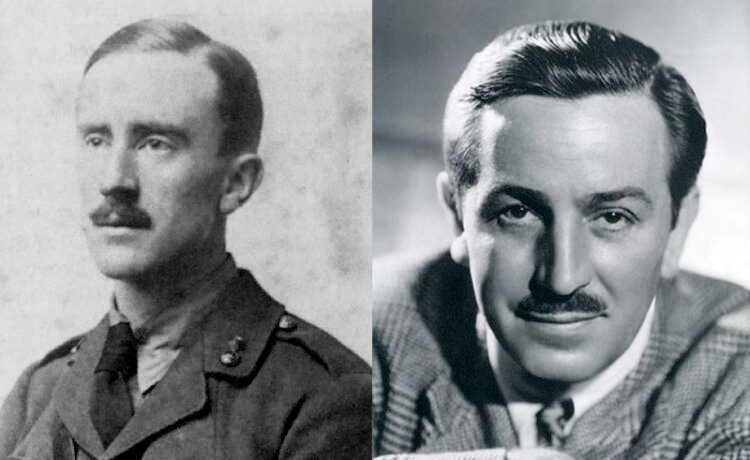

Image via Wikimedia Commons

I’ve just started reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit to my daughter. While much of the nuance and the references to Tolkienian deep time are lost on her, she easily grasps the distinctive charms of the characters, the nature of their journey, and the perils, wonders, and Elven friends they have met along the way so far. She is familiar with fairy tale dwarfs and mythic wizards, though not with the typology of insular, middle-class, adventure-averse country gentry, thus Hobbits themselves took a bit of explaining.

While reading and discussing the book with her, I’ve wondered to myself about a possible historical relationship between Tolkien’s fairy tale figures and those of the Walt Disney company which appeared around the same time. The troupe of dwarves in The Hobbit might possibly share a common ancestor with Snow White’s dwarfs—in the German fairy tale the Brothers Grimm first published in 1812. But here is where any similarity between Tolkien and Disney begins and ends.

In fact, Tolkien mostly hated Disney’s creations, and he made these feelings very clear. Snow White debuted only months after The Hobbit’s publication in 1937. As it happened, Tolkien went to see the film with literary friend and sometime rival C.S. Lewis. Neither liked it very much. In a 1939 letter, Lewis granted that “the terrifying bits were good, and the animals really most moving.” But he also called Disney a “poor boob” and lamented “What might not have come of it if this man had been educated—or even brought up in a decent society?”

Tolkien, notes Atlas Obscura, “found Snow White lovely, but otherwise wasn’t pleased with the dwarves. To both Tolkien and Lewis, it seemed, Disney’s dwarves were a gross oversimplification of a concept they held as precious”—the concept, that is, of fairy stories. Some might brush away their opinions as two Oxford dons gazing down their noses at American mass entertainment. As Tolkien scholar Trish Lambert puts it, “I think it grated on them that he [Disney] was commercializing something that they considered almost sacrosanct.”

“Indeed,” writes Steven D. Greydanus at the National Catholic Register, “it would be impossible to imagine” these two authors “being anything but appalled by Disney’s silly dwarfs, with their slapstick humor, nursery-moniker names, and singsong musical numbers.” One might counter that Tolkien’s dwarves (as he insists on pluralizing the word), also have funny names (derived, however, from Old Norse) and also break into song. But he takes pains to separate his dwarves from the common run of children’s story dwarfs.

Tolkien would later express his reverence for fairy tales in a scholarly 1947 essay titled “On Fairy Stories,” in which he attempts to define the genre, parsing its differences from other types of marvelous fiction, and writing with awe, “the realm of fairy story is wide and deep and high.” These are stories to be taken seriously, not dumbed-down and infantilized as he believed they had been. “The association of children and fairy-stories,” he writes, “is an accident of our domestic history.”

Tolkien wrote The Hobbit for young people, but he did not write it as a “children’s book.” Nothing in the book panders, not the language, nor the complex characterization, nor the grown-up themes. Disney’s works, on the other hand, represented to Tolkien a cheapening of ancient cultural artifacts, and he seemed to think that Disney’s approach to films for children was especially condescending and cynical.

He described Disney’s work on the whole as “vulgar” and the man himself, in a 1964 letter, as “simply a cheat,” who is “hopelessly corrupted” by profit-seeking (though he admits he is “not innocent of the profit-motive” himself).

…I recognize his talent, but it has always seemed to me hopelessly corrupted. Though in most of the ‘pictures’ proceeding from his studios there are admirable or charming passages, the effect of all of them is to me disgusting. Some have given me nausea…

This explication of Tolkien’s dislike for Disney goes beyond mere gossip to an important practical upshot: Tolkien would not allow any of his works to be given the Walt Disney treatment. While his publisher approached the studios about a Lord of the Rings adaptation (they were turned down at the time), most scholars think this happened without the author’s knowledge, which seems a safe assumption to say the least.

Tolkien’s long history of expressing negative opinions about Disney led to his later forbidding, “as long as it was possible,” any of his works to be produced “by the Disney studios (for all whose works I have a heartfelt loathing).” Astute readers of Tolkien know his serious intent in even the most comic of his characters and situations. Or as Vintage News’ Martin Chalakoski writes, “there is not a speck of Disney in any of those pages.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018.

Related Content:

J.R.R. Tolkien Snubs a German Publisher Asking for Proof of His “Aryan Descent” (1938)

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

J. R. R. Tolkien Writes & Speaks in Elvish, a Language He Invented for The Lord of the Rings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.