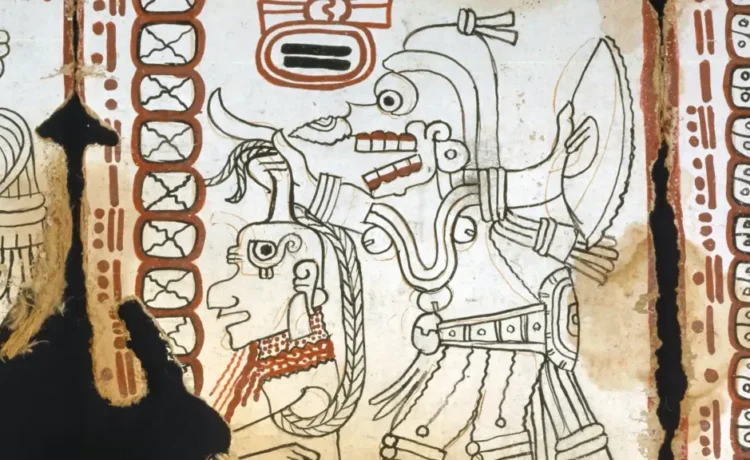

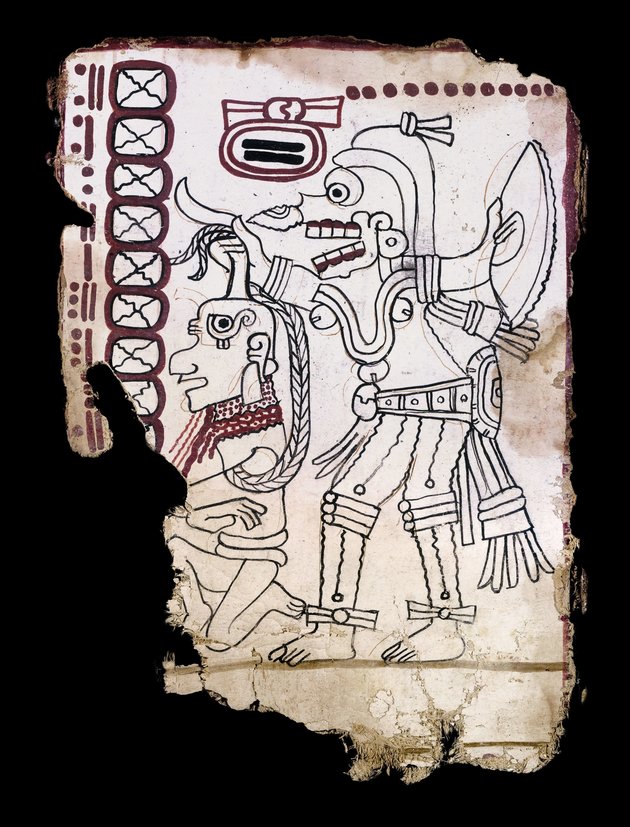

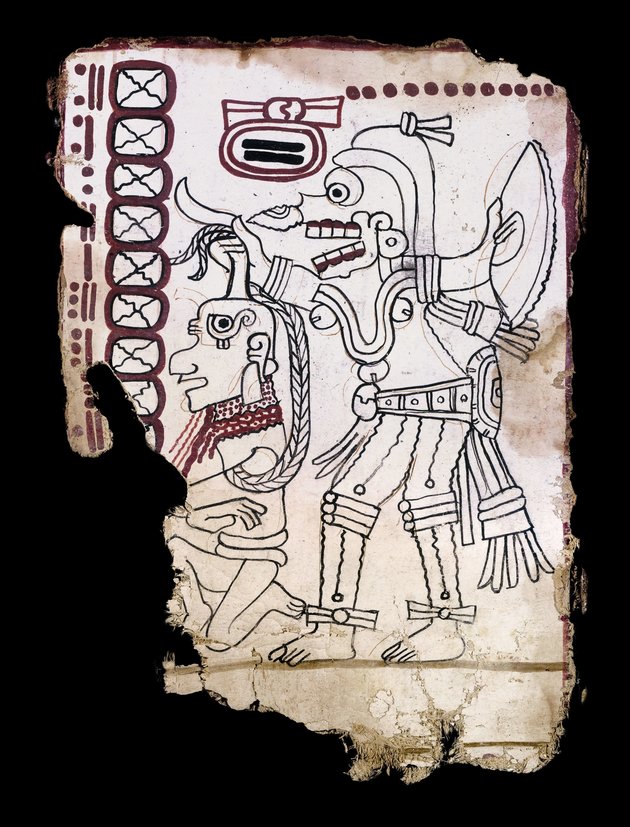

From the mighty Maya civilization, which dominated Mesoamerica for more than three and a half millennia, we have exactly four books. Only one of them predates the arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century: the Códice Maya de México, or Maya Codex of Mexico, which was created between 1021 and 1152. Though incomplete, and hardly in good shape otherwise, its artwork — colored in places with precious materials — vividly evokes an ancient worldview now all but lost. In the video above from the Getty Museum and Smarthistory, art historians Andrew Turner and Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank tell us what we’re looking at when we behold the remains of this sacred Mayan book, the oldest ever found in the Americas.

“This book has a controversial history,” says Turner. “It was long considered to be a fake due to the strange circumstances in which it surfaced.” After its discovery in a private collection in Mexico City in the nineteen-sixties, it was rumored to have been looted from a cave in Chiapas.

At first pronounced a fake by experts, due to its lack of resemblance to the other extant Mayan texts, it was only verified as the genuine article in 2018. For a non-specialist, the question remains: what is the Códice about? Its purpose, as Kilroy-Ewbank puts it, is astronomical, relaying as it does “information about the cycle of the planet Venus” — which, as Turner adds, “was considered a dangerous planet” by the Mayans.

The Códice contains records of Venus’ 584-day cycle over the course of 140 years, testifying to the scrutiny Mayan astronomers gave to its complicated pattern of rising and falling. They thus managed to determine — as many ancient civilizations did not — that it was both the Morning Star and the Evening Star, although they seem to have been more interested in what its movements revealed about the intentions of the deities they saw as controlling it, and thus the likelihood of events like war or famine. Those gods weren’t benevolent: one page shows “a frightful skeletal deity that has a blunt knife sticking out of his nasal cavity,” holding “a giant jagged blade up” with one hand and “the hair of a captive whose head he’s freshly severed” with the other. That’s hardly the sort of image that comes to our modern minds when we gaze up at the night sky, but then, we don’t see things like the Mayans did.

via Aeon

Related content:

A 400-Year-Old Ring that Unfolds to Track the Movements of the Heavens

The Ancient Astronomy of Stonehenge Decoded

How the Ancient Mayans Used Chocolate as Money

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.