If one of the presumed goals of president elect Donald Trump’s first round of tariff threats was to sow discord and division among Washington’s USMCA partners, it’s working like a dream.

For the best part of the past two weeks, Canada’s political leadership has been openly discussing the possibility of throwing Mexico under the bus in a (probably vain) attempt to appease Trump. Since two of Canada’s provincial premiers, Doug Ford of Ontario and Danielle Smith of Alberta, got the ball rolling two weeks ago by proposing to replace the USMCA trade deal with a bilateral agreement with the US, it’s been a pile-on.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that if Mexico did not tighten its policy against China, other alternatives would have to be sought. On the same day, the leader of Canada’s main opposition party, Pierre Poilievre, said he is willing to negotiate a trade agreement with the US that excludes Mexico.

Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s economy minister, deputy prime minister, WEF trustee, project Ukraine enthusiast, with Nazi skeletons in her closet, hinted in a televised interview that the US and Canada are more naturally suited trade partners due to their “comparable economic standards”:

“The second really important guarantee of that relationship [between Canada and the US] is the economic fundamentals. The reason we got to a good place with the new NAFTA is because our economic relationship, Canada’s economic relationship with the United States is a win-win economic relationship. It is balanced, it is mutually beneficial, it is based on two countries that have comparable economic standards trading together. And since we concluded that deal, the economic relationship with the United States has become stronger.”

Freeland also said that Canada is more aligned with the US than ever before on China (and, of course, most other things), as if this were a source of pride. The Trudeau government has already pledged to impose the same 100% tariffs on Chinese-made vehicles as the US as well as the 25% tariffs on Chinese steel. By toeing Washington’s line, Freeland says, Canada cannot possibly be seen as China’s backdoor into the US, adding that the same cannot be said of Mexico:

“I have heard personally from members of the Biden administration, members that have been strong supporters of Trump and his advisors, very grave concerns about Mexico serving as a backdoor for China into the North American trading space. I believe those concerns are legitimate and Canada, as a partner in the NAFTA trading area shares those concerns.”

At no point does Freeland provide any evidence to back up this claim; she just cites unnamed sources in Washington — perhaps as a throwback to her days as a journalist. She then went on to say that when it comes to the new NAFTA, the main priority for Canada is the strength of its relationship to the United States:

“It’s also really important for the United States. Canada is the largest market for the US in the world. Canada for US exports is more significant than China, Japan, the UK and France combined.”

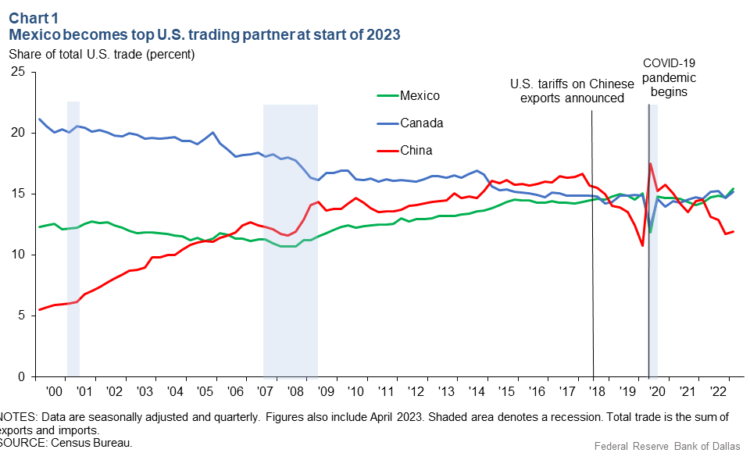

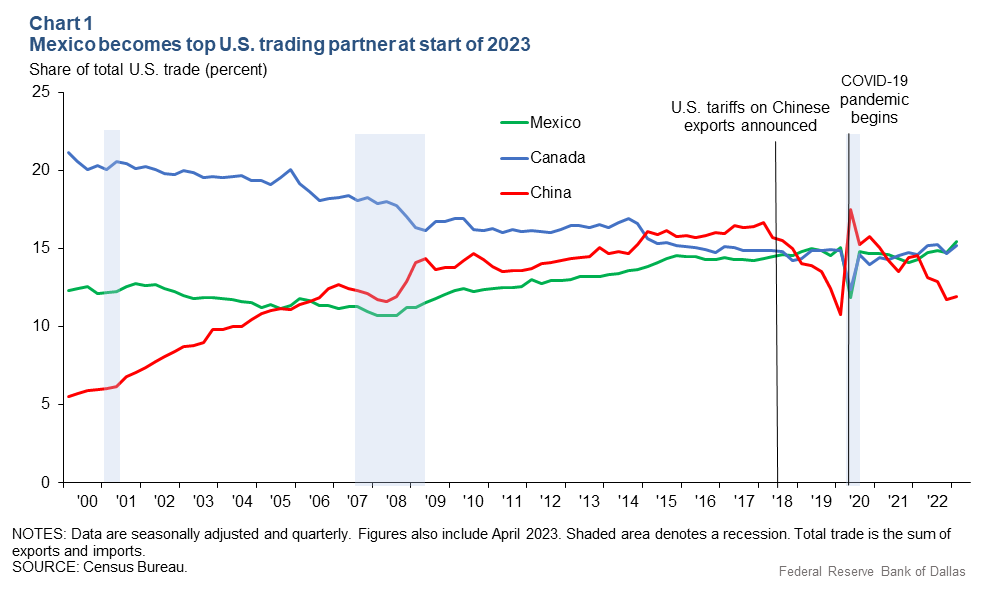

Strictly speaking, this may be true, but it is also misleading since it leaves Mexico completely out of the equation. As we reported last week, since the signing of the USMCA, Canada’s overall trade with the US has more or less stagnated, according to data from the US Census Bureau indicate. Meanwhile, Mexico has overtaken both China and Canada to become the US’ main trade partner, primarily as a result of the nearshoring trend sparked by the US’ trade war with China during the first Trump administration.

The insults have kept flowing Mexico’s way, and have even prompted a rare reprisal from Mexico’s usually calm and collected president. Yesterday, Sheinbaum said Canadians “could only wish they had the cultural riches” of her country. Probably the worst remark so far came from the lips of Ontario Premier Doug Ford:

“To compare us to Mexico is the most insulting thing I’ve ever heard from our friends and closest allies, the United States of America. I found Trump’s comments unfair. I found them insulting. It’s like a family member stabbing you right in the heart.”

These sorts of comments have been seen as a betrayal in Mexico, particularly given the lengths to which Mexico’s former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO) reportedly went to secure Canada’s inclusion in the USMCA deal in the face of stiff opposition from Trump. If it hadn’t been for AMLO’s intervention, Canada may never have been invited to join USMCA. Mexico’s lead trade negotiator, Gutierrez Romano, told Canadian newspaper the Globe and Mail last week that “it is not rational to be divided against the United States”. He has a point.

But what if Canada were to carry through on its threats to kick Mexico to the curb? Would that really be such a bad thing for Mexico?

The answer is: probably not, as long as Mexico’s trade with the US remained more or less constant (I know, big “IF”, but please humour me here, this is purely about Canada and Mexico). As we noted last week, Mexico and Canada may be partners in the same trilateral trade agreement but they are ultimately competing for the same prize — US market share — and Mexico is, to all intents and purposes, winning the race.

By contrast, the trade between the two countries is relatively modest. In the first three-quarters of 2024, Canada sold $309 billion worth of goods and services to the US and just $9.6 billion to Mexico. And while Canada has a trade surplus with the US, its trade balance with Mexico is constantly in negative territory. In the first nine months of this year alone, it has clocked up a trade deficit with Mexico of $4.28 billion

In fact, on balance a life without Canada would probably be broadly positive for Mexico’s economy, its workers, indigenous communities and, most importantly, its environment, given the predominant nature of Mexico’s bilateral trade with Canada: mineral extraction.

“Bad Neighbour, Worse Trade Partner”

A new in-depth investigation by the Mexican online news website Sin Embargo — titled “Bad Neighbour, Worse Trade Partner: Canadians Siphon wealth from Mexico for Next to Nothing. And They Still Wrangle on Taxes” — highlights a glaring paradox behind Ottawa’s threats to throw Mexico under the bus: doing so would jeopardise a trade relationship that disproportionately favours Canada’s mining companies, for whom Mexico has been a veritable paradise of mineral abundance and lax regulations for the past 32 years:

In recent days, a group of Canadian politicians suggested to the President-elect of the United States, Donald Trump the idea of expelling Mexico from USMCA… and forging a bilateral agreement between Canada and the US. However, the [first NAFTA agreement] together with the Mining Law (1992) passed by then-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari is the legal scaffolding that has granted huge benefits and privileges to transnational mining companies, mainly Canadian and American.

“The USMCA has always favoured Canadian companies since 1992 because the entire regulatory framework in Mexico was modified in line with NAFTA (now USMCA),” said Beatriz Olivera, director of Energy, Gender and Environment (Engenera). “New conditions were established so that they could access water, territory, reduce procedures, so that they did not have to carry out environmental processes and consultation of indigenous communities. The entire Mining Law of 1992 was adapted according to the standards of the USMCA just to facilitate and favour foreign investment — in this case, Canadian and U.S. investment. If we look at the mining period before the USMCA there was not all this social conflict, murders of [environmental and human rights] defenders, complaints about land and water use.”

Mexico is the world’s largest silver producer, accounting for roughly one out of every five metric tons of the precious metal mined in 2021, while Canada is home to the headquarters of 75% of all international mining companies, 60% of which are listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX).

Mexico is also among the top ten global producers of 15 other metals and minerals (bismuth, fluorite, celestite, wollastonite, cadmium, molybdenum, lead, zinc, diatomite, salt, barite, graphite, gypsum, gold, and copper). And in 1992, Carlos Salinas y Gotari’s Mining Law decreed that mining activity took precedence over all other industries and activities. Article 6 of the law reads:

The exploration, exploitation and beneficiation of the minerals or substances referred to in this Law are public utilities and will have preference over any other use or utilization of the land, subject to the conditions established herein, and only by a Federal Law may taxes be assessed on these activities.

Thanks largely to this three-line paragraph, the claims of the mining industry on Mexican land have had greater import than not just all other industries but all other human activity. During the three decades that have followed, Mexico’s federal government has been bound by law to act against the interests and rights of both private landlords and local communities in order to guarantee mining companies access to the lands upon which a concession is granted.

“No other mining law on the continent grants preferential access over any type of land use,” Jorge Peláez Padilla, a professor of law at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), told the investigative journalist website Contralinea in 2013. The result has been rampant expropriations of private — and in some cases communal or even protected park — land, for the sake of private mining operations.

Canadian-based firms have been the biggest beneficiaries, scooping up roughly seven out of ten licenses granted to foreign mining companies. In 2021, La Jornada reported that around 75% of the mining concessions that were granted in the pre-MORENA administrations (none have been granted since AMLO took office in 2018) were to foreign mining companies, most of them Canadian, according to data from the Ministry of Economy. As the Canadian independent journalist Yves Engler documents, all of this was facilitated by NAFTA:

There were no Canadian mines operating in Mexico in 1994. By 2010 there were about 375 Canadian-run projects. Before the reforms that came with the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico’s constitution dictated that land, subsoil and its riches were the property of the state and recognized the collective right of communities to land through the ejido system. Constitutional changes in 1992 allowed for sale of lands to third parties, including multinational corporations. Combined with a new Law on Foreign Investment, the Mining Law of 1992 allowed for 100 percent foreign control in the exploration and production of mines.

Today, Canadian companies dominate Mexico’s gold and silver mining sectors, extracting around 35,000 kilos of the yellow metal annually — the equivalent of 60% of all the gold mined each year. By contrast, Mexican companies extract 17,300 kilos, roughly 30% of the total. The remaining 10% is mined by US companies. For Mexico’s finances and communities, the deal has been rotten from the get go, explains Sin Embargo.

The extraction of gold and silver from Canada’s more than 300 mining projects spread throughout Mexico has caused environmental and social devastation in communities. Despite the profits for Canadian mining companies and the damages for Mexico, protected by the USMCA, the projects contribute less than 1% of total tax revenues and 0.62 percent of secured employment per year, according to official figures analysed by the organization Engenera. Even First Majestic Silver initiated arbitration three years ago against its debt of 180 million dollars to the SAT.

That’s right: one of the mining companies has actually sued the Mexican State for trying to claw back years of unpaid taxes. This is all par for the course for Canadian mining companies, particularly in Latin America and Africa.

In 2017, BBC World released a report (in Spanish) on the often unsavoury business practices of Canadian mining companies in Latin America. Titled “The Conflicts and Controversies of Canadian Mining in Latin America (Which Clash With the Country’s Progressive Image)”, the article included the following passage (translated by yours truly):

Canada’s influence on mining is felt in Latin America more than in any other region of the world.

More than half of the country’s mining investment abroad is in [the] region, with 80 large projects.

It is perhaps inevitable that, given the number of mining projects, Canada is a lightning rod for criticism directed at mining in general.

But expectations were different when Canadian miners landed in the 1990s.

“Canadian mining came riding a discourse of clean mining and development aid,” Cesar Padilla, spokesman for the Observatory of Mining Conflicts in Latin America (OCMAL), an NGO critical of multinational mining companies, told BBC Mundo. “And ultimately they didn’t keep most of the promises and commitments they made”.

“Some Canadian mining companies have been characterized by large and long conflicts with communities, which bears little relation with the projected image of responsible modern mining…”

In April 2016, Justin Trudeau received a letter from more than 180 non-governmental organizations in Latin America and other countries urging him to regulate the behaviour of Canadian mining companies abroad. He ignored it.

Many cases of corporate abuse and environmental harm have found their way to the UN Human Rights Council. From Mining Watch Canada:

Today, corporate accountability experts sent a 30-page submission to the UN Human Rights Council ahead of its April 2023 Universal Periodic Review of Canada, denouncing Canada for its continued diplomatic support of mining companies over the safety of human rights and environment defenders (HRDs).

“We have found that Canadian embassies continue to provide significant support for Canadian mining companies despite being aware of serious and credible allegations of human and environmental rights violations,” says Charis Kamphuis, TRU law professor and JCAP board member. “The Universal Periodic Review is a crucial opportunity to shine the spotlight on Canada and reveal the massive gulf between Canada’s domestic and international human rights commitments, and the actions and omissions of Canadian officials who consistently ignore the concerns of affected communities and the risks to defenders. In some cases, Canadian officials have taken steps to undermine communities’ efforts to defend their rights and access justice.”

A Mining Paradise No More?

But things are beginning to change in Mexico. Last year, the AMLO government began dismantling the preferential treatment for mining exploration and exploitation. As we reported at the time, the reforms, among other things, shortened the length of mining concessions, tightened the rules for water permits, expanded the grounds for cancelling licenses, and banning the granting of mining concessions on protected parkland. However, the law was blocked by a Supreme Court injunction presented by Mexico’s opposition parties.

Now, the government wants to go a step further and introduce an almost total ban on open pit mining and fracking into the country’s constitution. In a package of reforms sent to the legislature in his last month in office, AMLO included a modification to Article 27 to “prohibit both the granting of concessions and the activities of exploration, exploitation, benefit, use or exploitation of minerals, metals or metalloids in the open air.”

As I wrote at the time, if this package of reforms is approved, which is likely given the size of the government’s majorities in both houses, it could end up having an impact on mining not just in Mexico but also globally, especially if other national governments in the region and beyond are inspired to take similar steps. And that would represent a direct threat to the interests of the legions of mining companies headquartered in Canada. Just last week, Mexico’s finance ministry (SHCP) proposed increasing mining royalties and closing tax loopholes.

Given all this, it is probably safe to assume that Canada’s recent treatment of Mexico is motivated as much, if not more, by concerns about Mexico’s shifting regulatory landscape for mining companies as it is about China using Mexico as a back-door entry point to the US and Canadian markets. By threatening to push Mexico out of USMCA, Canada’s government, in classic mafia-style, is sending a clear message: no more moves against our mining interests. Or else.

As Sin Embargo points out, Canadian miners will probably find succour in the text of the USMCA agreement, anyway. In the section on the Environment, the USMCA states:

“The Parties further recognize that it is inappropriate to establish or use their environmental laws or other measures in a manner that constitutes a disguised restriction on trade or investment between the Parties.” (Chapter 24, Article 2, section 5).

Mexico is already the most sued member of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), as well as the most sued country at the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in 2023, with a total of ten ISDS cases brought against it. Continued membership of USMCA will inevitably mean more investment disputes, more fines, and more pressure to dampen its reform agenda, whether on mining, GMO corn, energy, housing, water management or workers’ rights.

It would also mean facing rising pressure from its two North American trade partners to cut itself off from China and any other nations they disapprove of, and gradually subordinate its national interest to that of the US, just as Canada has done.

In light of these two reasons alone, there is, I believe, a pretty solid case that Mexico would be better off without Canada as a trade partner. It would also regain control over its strategic mineral resources, including its deposits of gold and silver — two metals that have gained significantly in value of late. In the case of gold, it is not just gaining in value but also importance, recently surpassing the euro to become the second-largest reserve asset for global central banks. Given the sheer size of Mexico’s silver deposits, some are arguing that the precious metal should also be turned into a strategic reserve asset.

Of course, this is all highly unlikely to happen, even as the threats and insults fly between the two feuding neighbours. Discord and division may be rising among the NAFTA partners but this 30-year trade agreement still has plenty of inertia on its side, even as Trump threatens to violate the very essence of the deal he helped broker by imposing blanket tariffs on the others’ products. My guess is that Mexico will be the last of the three countries to walk away from the deal — there’s just too much at stake for the country’s economy — while Canada has more to lose than gain from throwing Mexico under the bus.