Since 1930, type Ia supernovae have been thought to arise from white dwarfs exceeding the Chandrasekhar mass limit. Here’s why that’s wrong.

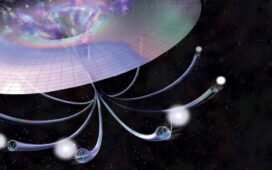

Whenever a star is being formed, there will be two opportunities throughout its life to go supernova. The first comes early on: if the star is massive enough, when it exhausts first the hydrogen and next the helium within its core, it can continue onwards and fuse carbon, neon, oxygen, and then silicon in succession, until the core at last implodes, resulting in a core-collapse (type II) supernova. If the star isn’t massive enough to succumb to that fate, it will blow off its outer layers after helium-burning and form a planetary nebula, while the core contracts to form a white dwarf. If that white dwarf then experiences the right conditions, its interior will detonate, producing a different (type Ia) class of supernova: the most distant “standard candle” known in astronomy.

Since the 1920s and 1930s, it’s been known that — above a certain mass threshold — white dwarfs would become unstable against gravitational collapse. The presence of electrons, and the fact that no two electrons in the same system can ever occupy the same quantum state, is what prevents white dwarfs from imploding. However, above a…