By Dr. Jacqueline Shin, MHT National Register Assistant

Nominations to the National Register of Historic Places do not offer the last word on any historic property; rather, they are living documents that can be amended as researchers discover more information. And as times change, so too does what new generations of historians and historic preservationists pay attention to and value, which is the case for the stories of historically marginalized communities, which have traditionally been ignored and left out of the historical record. To address these gaps, the National Park Service (NPS) offers an Underrepresented Communities Grant Program, specifically intended to help develop and amend National Register nominations, as well as to undertake surveys of historic properties associated with groups, including women, that are underrepresented in the National Register.

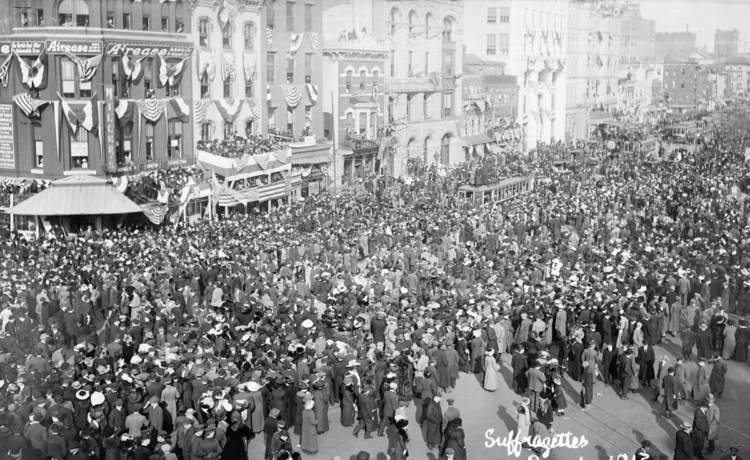

The suffrage parade through Washington, DC in which African-American suffragists were segregated, March 1913 (LOC).

In 2023, NPS accepted the Women’s Suffrage Movement in Maryland Multiple Property Submission, completed by Kacy Rohn, which linked suffragists in Maryland to significant sites in the state. This work, funded by an NPS Underrepresented Communities Grant in 2017, set the stage for researchers to develop and amend National Register nominations for places associated with women’s fight for the vote. One such researcher is Nicole A. Diehlmann, who recently undertook the amendment of eight historic properties listed in Baltimore.

This blog post highlights two of these new National Register amendments: the Old West Baltimore Historic District and Sharp Street United Methodist Church and Community House, which were approved by NPS in September of 2024. In addition to documenting the importance of these places to women’s history, these two amendments also demonstrate the exclusionary nature of the women’s suffrage movement, as well as the determination and powerful activism of African American women in Baltimore and across Maryland.

The Old West Baltimore Historic District—which includes neighborhoods like Upton, Marble Hill, Harlem Park, and Sandtown Winchester—was established as an elite suburb that was initially occupied by German immigrants. Due to “white flight” and segregation, it became the city’s premiere African American neighborhood in the first half of the 20th century. Large numbers of the city’s Black population lived here, including an affluent and educated upper-middle class whose members led many social, fraternal, civic, and religious organizations. The amendment to this district highlights nine buildings associated with the women’s suffrage movement – these are primarily the homes of advocates for women’s suffrage, as well as institutional buildings such as the Young Women’s Christian Association branch and two churches.

Rather than welcoming all activists as members, women’s suffrage organizations excluded African American individuals. In response, Black women in Baltimore promoted suffrage through existing African American civic organizations. They also established their own organization in 1915, the Woman’s Suffrage Club (later called the Colored Woman’s Suffrage Club and the Progressive Woman’s Suffrage Club), which was led by women including Estelle Young, Margaret Briggs Gregory Hawkins, and Augusta Lewis Chissell. After the passage of the 19th Amendment, organization leaders shifted their focus to voter registration and education. Chissell wrote a column in the Baltimore Afro-American called “A Primer for Women Voters,” which was intended “for the benefit of women who wish to inform themselves in regard to their newly acquired duties and privileges as voters and citizens” (Afro-American 1920, 6).

Top: Margaret Briggs Gregory Hawkins House (left) and Augusta Lewis Chissell House on Druid Hill Ave in the Old West Baltimore Historic District. Bottom: Estelle Young, Margaret Hawkins, and Augusta Chissell

The Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church, located on Dolphin Street in Baltimore, is a well-known site of civil rights activism within Old West Baltimore. Prominent members of the congregation included Lillie Carroll Jackson, who served as the president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1935 until 1970, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The church hosted a debate in April 1909 between Howard University and Lincoln University students on the topic, “Should the Suffrage be Extended to Women?” Over a thousand people attended the debate. The church also hosted a mass meeting in October 1915 where noted educator, athlete, and activist, Lucy D. Slowe, secretary of the Baltimore branch of the NAACP, gave a talk that helped catalyze the African American women’s suffrage movement. This significant event may have helped launch the above-mentioned Woman’s Suffrage Club.

Sharp Street Memorial United Methodist Church (left: undated image, right: 2017)

Although excluded from white women’s suffrage organizations, Black women joined together to fight for all women’s right to vote. They drew on the large and active social scene in Old West Baltimore and their extensive experience protesting discrimination and segregation as well as actively promoting civil rights. Black women in Maryland had been active in preserving the voting rights of African American men, opposing the Digges amendment in 1910, which would have disenfranchised large numbers of voters. Paraphrasing scholar Martha S. Jones in her recent book, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, the histories of Old West Baltimore and the Sharp Street Church exemplify Black women “building power where they could,” cracking open a door with the 19th Amendment that others who came after would push open.

To learn more about Maryland’s role in the suffrage movement and find information on key suffragists, be sure to check out the StoryMap, “Maryland Women’s Fight for the Vote,” created for MHT by Kacy Rohn, and the multi-media public history project, “Ballot & Beyond,” produced by Preservation Maryland with support from MHT and Gallagher Evelius & Jones. The Maryland Center for History and Culture also has a blog post on the June 1912 Baltimore parade.

There are also several articles on the MHT blog, “Our History, Our Heritage,” about the women’s suffrage movement:

To learn about the other National Register amendments submitted under the Women’s Suffrage Multiple Property Submission, stay tuned for Part 2.